Beyond Lines of Demarcation: Borders as Buffers

By Bogdan G. Popescu

Security concerns often demand the establishment of institutions in border areas that are different from the rest of the civilian territory. Scholars suggest that individuals residing in the frontier zone frequently experience distinct injustices as a result of state attempts to both defend the periphery and subjugate its inhabitants in the interests of state security. At the same time, existing literature also portrays borders as spaces for fugitivesand individuals seeking refuge from state authorities. They can be areas subject to shared administration by neighboring nations, blurring the lines of sovereignty. Borders also may challenge notions of nationality and ethnicity.

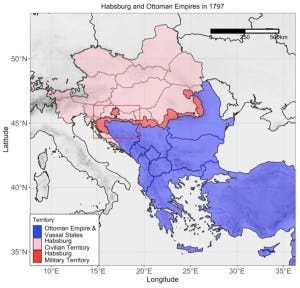

Few studies however examined the distinct institutions within these border areas and their long-term consequences. Generally, there is a scarcity of research exploring the impact of policies implemented in the spaces between states, particularly within a historical context. In a recently published article and an upcoming book, I fill this gap in the literature by exploring institutions developed in the border area and their long-term effects. I concentrate on the buffer zone between the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires, two historical states that ruled over parts of Central and Eastern Europe for centuries, to demonstrate the inner workings and legacies of such institutions.

I focus on a significant segment of the Habsburg buffer border area, which corresponds to the present-day territory of Croatia, also described by historians as the Habsburg military colony. Established in 1553, this buffer territory served as a defensive measure by the Habsburg Empire against the Ottoman threat until its abolition in 1881. Figure 1 depicts the outline of the buffer area in red within the Habsburg Empire, depicted in pink.

Characteristics of the Habsburg Military Frontier

The Habsburg military buffer area in this region involved several key features.

Firstly, there was a substantial transformation of the local society in 1551 when the area received a special legal status. This involved the removal of large landowners, the institutionalization of communal property arrangements (called zadruga in Serbo-Croatian or hauscommunität in German), and the appointment of imperial governors from Vienna. These measures aimed to assert control and reshape the social fabric of the territory, which was labeled a “military colony:” a territory with an “endless” supply of self-sufficient soldiers. Secondly, the infrastructural investment in the region was intentionally limited. The goal was to prevent disruption to the existing social organization within the colony. Thirdly, the labor market in the Habsburg military colony exhibited inflexibility, which effectively compelled locals to engage in specific jobs dictated by the empire: military patrol along the border and defense in case of attacks by the Ottomans.

Previous research on the legacies of the Habsburg state focused on the empire as a whole and compared it to other neighboring countries. Habsburg successor states generally display higher institutional trust, possess more efficient bureaucratic systems, maintain persistent religious practices, and uphold beliefs in democratic ideals. Furthermore, higher levels of human capital have also been observed. However, existing studies have typically assumed homogeneity in Habsburg institutions across their entire territory, with limited attention given to the distinctive political structures present in border areas.

To evaluate the short and long-term effects of military colonialism, I used a geographic regression discontinuity design, taking advantage of the discontinuous nature of the border between the Habsburg civilian territory and the Habsburg military colony. Results using a variety of historical censuses that I digitized from the time of the Habsburg Empire, Yugoslavia, Kingdom of Croatia, and modern-day Croatia suggest that the former military space had lower access to public goods, including roads, railways, and lower access to medical care.

Additionally, the communal property arrangements outlived the formal disbandment of the military colony. Analyses using the census from 1895, which is 14 years after the formal abolition of the border, indicate that communal properties were much more prevalent in the former buffer area. This means that people were much more likely to live as extended family clans: between 12 and 60 individuals living together, without individual property until around 1920.

Historical ethnographic accounts indicate the communal properties played an important role in ensuring the subsistence of soldiers. Military officers could go on border patrol while their means of subsistence would be taken care of by the extended family. As the military colony became obsolete, family clans continued to play important roles. For example, a former zadruga member who was interviewed in the 1940s provides a nostalgic account about the services that members were (no longer) benefiting from: “[now] the wife has to take care of everything by herself, the children, the livestock, the heavy work in the fields, the cooking, the making of clothes…and along with all that there are worries and troubles” (Erlich, 1966, p. 58). Such services constitute the reason why zadrugas did not disappear immediately after the dissolution of the military colony. Therefore, zadrugas continued to exist until around 1918.

The following picture illustrates how soldiers were expected to dress during the time of Maria Theresa, ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780.

Finally, the next picture shows one medium-sized zadruga or military extended family clan from the early 20th century.

Legacies on Norms and Attitudes

In the short run, historical anthropologists confirm the persistence of “collectivist attitudes” as a result of the longer persistence of zadrugas in the former military colony. “Individualistic trends” only started emerging during the interwar period. Modern individual-level surveys (2010-2016) also indicate some interesting patterns: people in the former military area trust other people less, and trust members of their family more compared to civilian area. When it comes to attitudes towards the state, people in the former military colony trust the presidency less, and they think that they frequently have to bribe the road police, and to get unemployment benefits.

Take-Aways

States employ diverse approaches to address their security concerns, but there is a paucity of research on the long-term consequences of policies implemented by the central authority in peripheral regions. This project focused on exploring the specific approach adopted by the Habsburg Empire in response to the security threat posed by the Ottoman Empire.

In order to safeguard the border against the Ottomans, the Habsburg Empire introduced a unique category of imperial subjects known as colonists. These individuals were granted land in exchange for their commitment to defend the border. The status of a colonist entailed several distinct characteristics: 1) limited access to public infrastructure; 2) life under communal property rights; 3) and a rigid, state-regulated labor market. Exposure to such policies led to deleterious contemporaneous and long-term outcomes.

The Habsburg military colony is not unique to the Habsburg Empire. In fact, the Habsburg military colony constituted an example for other contemporaneous empires, such as the Russian Tsardom and French Algeria. Check out the upcoming book that discusses in detail the dialectical exchanges in Paris and Sankt Petersburg that demonstrate how the Habsburg military colonial model was adopted in other territories.