Blood and Iron: Political Fragmentation in the Ancient Eastern Mediterranean

How new technology reshaped the political equilibrium of the early Iron Age through violence.

Around 1200 BCE, a societal shift happened in the Mediterranean basin. The great Bronze Age empires that characterized the era shrank or outright collapsed. The world that emerged from the ashes was not another one of mega-empires, but rather one of smaller and more politically diverse polities.

Historians and political scientists have suspected that iron technology may have played a crucial role in this political transformation. Josiah Ober (2015) observed that the availability of iron relative to bronze made it difficult for Iron Age elites to monopolize violence potential. Scheidel (2017) concurs and notes that by the 6th century BCE, a large portion of the Greek-controlled lands had developed a citizen-centered culture characterized by citizen participation in war. Manning (2018) observes that iron led to new warfare and farming techniques, turning the landscape from large cities to dispersed walled villages. Boix (2015) tells the story through looters and producers, and how iron allows the producers a new level of defense. Until now, scholars have not measured the effect or prove the connection using statistical methods.

My study, using digitally constructed maps of the Eastern Mediterranean from the 14th to 8th centuries BCE, provides the first empirical evidence of iron’s revolutionary impact on political power. The findings support the previous research by showing that after regions switched to primarily iron, they experienced over a 100% increase in political fragmentation, more than doubling the number of polities within a given area.

The Bronze Age

In order to appreciate the impact of iron metallurgy, we must examine the world of the late Bronze Age and the political equilibrium iron disturbed. Bronze requires two key components: copper and tin. Copper, while not overly abundant, could be found in several scattered deposits across the Mediterranean. Tin, which was approximately 12% of bronze, was extremely rare with the main deposit in the East being located in modern day Afghanistan. This scarcity led to high prices, creating a perfect monopoly situation for Bronze Age elites.

Bronze weapons and tools were expensive to produce and were restricted to mostly the wealth ruling class and the warriors they chose to outfit. This situation gave Bronze Age elites military superiority over their subject and neighboring smaller polities who may not have been able to meet the weaponry cost. The result was a trend toward large centralized empires that could project military power across vast territories. My study shows that the introduction of bronze is associated with around a 50% decrease in the number of polities within an area, as larger and wealthier polities conquered others.

Blood and Iron

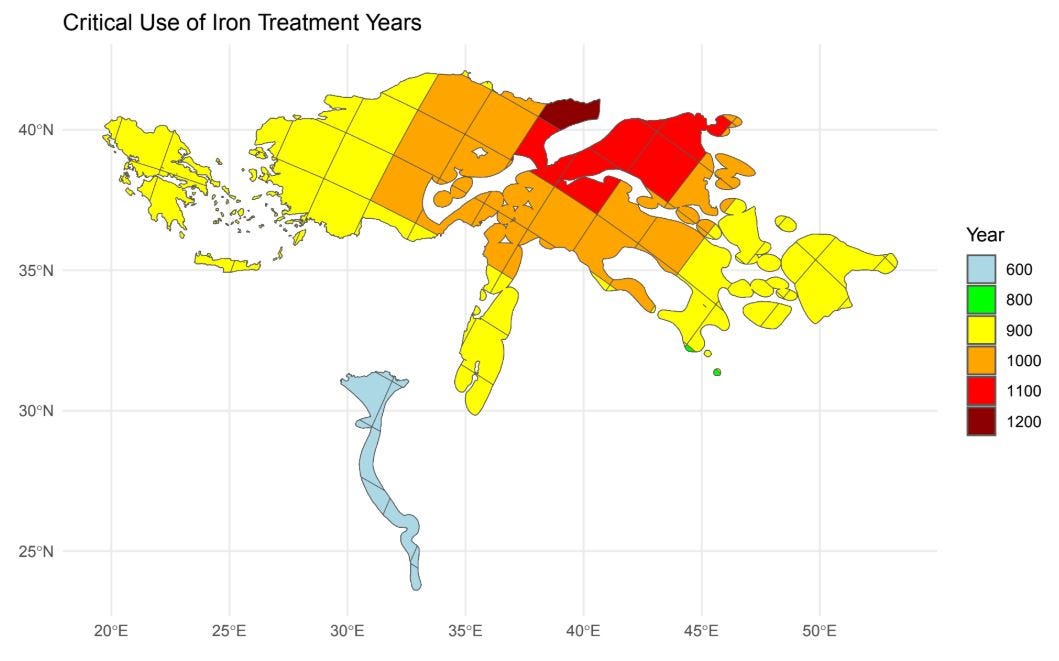

Beginning in 1200 BCE, a new technology started to disseminate from what is today the country of Georgia: iron. Although societies had been aware of and worked with meteoric iron for centuries, learning to work local deposits was revolutionary. Unlike the scarce tin required for bronze, iron ore is to this day one of the most abundant metals on Earth. For the first time in centuries, “ordinary farmers and herdsmen thereby achieved a new formidability in battle” as William McNeill (1982) puts it. Small, poor communities could afford to arm themselves with weaponry comparable to those of the elite.

In Greece, a few Mycenaean kingdoms gave way to hundreds of city-states. Even using conservative estimates there was a 50-fold increase in polities within the mainland and Aegean islands. In the Northern Levant, the Hittite Empire’s collapse was followed a fragmentation region of Neo-Hittite and Aramean city-states who were unable to achieve the territorial scale of their Bronze Age predecessor. In the Southern Levant, the withdrawal of the Egypt left a power vacuum filled by competing kingdoms of Israel and Judah, as well as numerous Phoenician city-states. On the Iranian Plateau, Assyrian records describe the Iranian Medes societies as numerous and small fragmented polities. A stark contrast the unified Bronze Age Assyria.

This was not just about individual weapons being cheaper. Iron technology enabled smaller polities to field armies that could compete with their larger neighbors. The late Bronze Age equilibrium was broken by iron. The number of polities within a region more than doubled in some areas.

Measuring Fragmentation

Although there is previous research and historical qualitative evidence to demonstrate that this link between iron and fragmentation is real, my study focuses on not only on testing the theory, but on measuring this impact. Did it actually happen and if it did, was it actually a large effect?

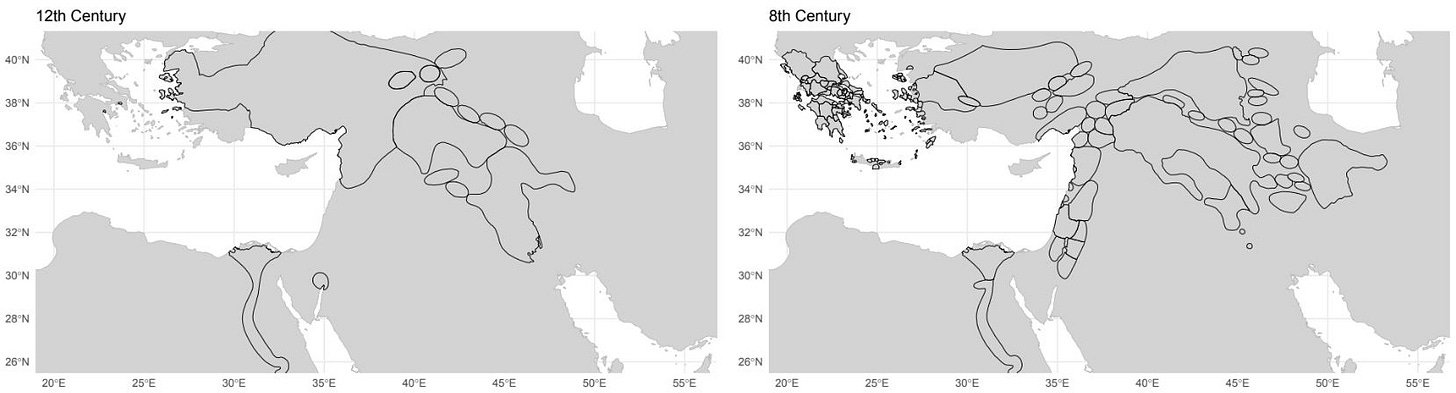

In order to quantify iron’s impact on fragmentation, I created digital maps showing political boundaries across the Eastern Mediterranean from 1400 to 800 BCE. I then divided the region into grid-cells.

The map data comes from multiple sources. The main source for the MENA region is Brill’s Historical Atlas of the Ancient World. Mycenaean and Iron Age Greece required more specialized studies. Several sources were used to carefully reconstruct Mycenean Greece and later Greek poleis that were politically independent. The data for iron adoption was taken from Peter Turchin and co-authors (2021) and measured when iron became the metal used in weaponry or tools. The benchmark was iron replacing 70-80% of bronze weapons and tools within a region.

Using a two-way fixed effects model, and controlling for geography climate, and competing military technologies, I estimated the effect of iron on fragmentation. Fragmentation was measured as the number of polities per grid-cell in the main specification. The best way to see these results is in the following figure which nicely illustrates the positive impact of iron metallurgy on the number of polities.

Pathways to Fragmentation

But how exactly did iron shatter the equilibrium of political centralization? The cause is multi-faceted, though I present four reinforcing mechanisms:

Increased Interpersonal Violence

Recent research by Baten et al (2023) found that archaeological sites with iron weapons showed higher rates of violent injuries in skeletal remains. Although iron increased political competition at the higher level of polity, it also democratized violence at the individual level, leading to higher rates of violence. This could potentially make polities more difficult to govern as both the elite class and their subjects can kill each other more easily.

Increased Polity Warfare

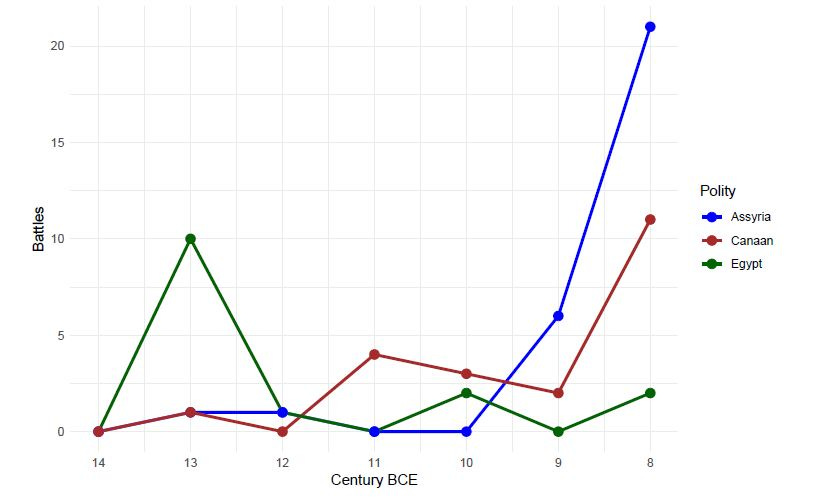

Although interpersonal violence increased, so too did violence between polities. An analysis of battle records shows an uptick in conflicts as a polity adopts iron. Egypt, which did not reach the iron adoption threshold until 600 BCE, shows relatively low levels of conflict throughout my study. Assyria and the Canaanite region in contract show dramatic increases in warfare after reaching the iron threshold in the 9th century BCE. These upticks are concurrent with empire-building attempts, showing that while iron democratized violence potential, it does not mean new polities were not imperially-minded like their predecessors.

Political Instability

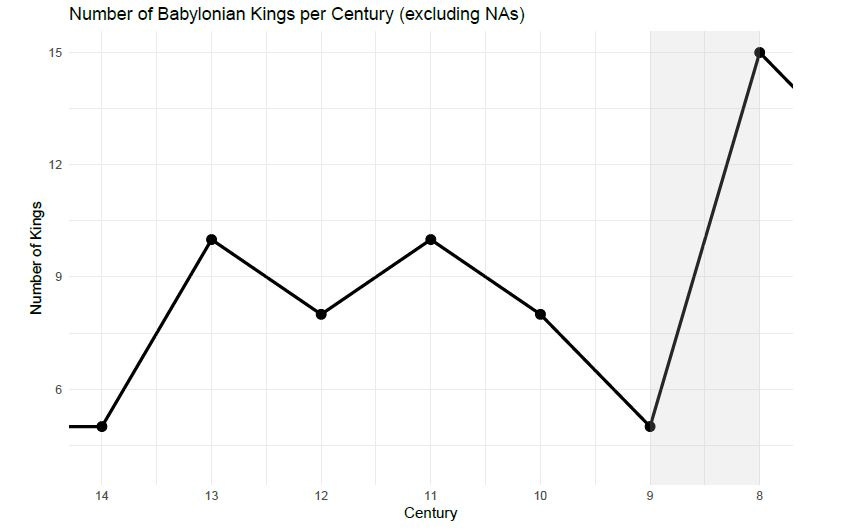

Iron democratizing warfare leads to political instability. Tracking ruler turnover in Babylon, Assyria, and mythological records of Athens shows a striking pattern. All three polities saw an increase in leadership turnover per century following iron adoption. When violence becomes cheaper, changing an unpopular ruler becomes more feasible. Increased political instability also works against imperial expansion, leading to a more fragmented landscape of smaller polities.

Population Growth

Iron adoption not only lowered the cost of weapons, but also that of agricultural tools that enabled agricultural improvements in settlements of previously marginal areas. Comparing population numbers before and after iron shows a remarkable increase in population. Increased population means that communities could field larger armies. A larger army could support independent polities organization in areas previously ruled by foreign entities.

Why should we care?

The ancient iron revolution is not just ancient history. It fundamentally reshaped the political landscape throughout the ancient world. The fragmented city-states of Greece laid the groundwork for innovations in governance. The competing kingdoms of Israel and Judah created one of the most enduring religions the world has seen. Iron changed development in the ancient world.

Understanding how military technologies affect political power remains as relevant today as it did in 1200 BCE. Just as iron democratized violence in the ancient world, modern technologies reshape the balance of power between states and between individuals within states. Technologies being developed now can reshape the political landscape of the world.

is there a parallel here to gunpowder? i.e. european feudal era cavalry, expensive and needing trained warrior elites to maintain - giving way to relatively untrained masses, and then the eventual political grants to reward those masses? The only difference is that you seem to be saying that bronze (centralized kingdoms) -> iron (democratized, more polities) but definitely the shift from cavalry to gunpowder saw the reverse.

The question is whether technology of the future will lead to further centralization or fragmentation. This seems to be dependent on the scale of supply chains required. I think AI tends to favor centralization, while biotech tends to favor fragmentation.