Bridges of Communication: The Persistent Effects of Bible Translations in Africa

By Gabriel Brown

The persistent influence of historical missionary activity on sub-Saharan Africa is at this point well-documented. Missionaries played a large role in shaping the religious landscape but also had long-term influence on literacy, health, intergenerational mobility and even homophobia. However, less is known about how missionaries had such long-lasting effects. One key missionary investment can help explain this: Bible translations into vernacular African languages.

Guided by the principle of Sola Scriptura, Protestant missionaries in Africa translated the Bible into hundreds of languages starting in the early 19th century. According to this principle, the Bible is the sole authority of Christian faith. Thus, making the Bible available in the vernacular languages of Africa was of paramount importance to Protestant missionaries. Historians have argued that these translations had transformative effects on African society. They point to how, prior to missionary arrival, African languages were primarily oral; Bible translations were the first major written work in the language. The dialect used in the Bible became the standard one. However, the missionary’s role did not end with making the Bible available, Africans actually needed to be able to read it. Thus, alongside Bible translations came the establishment of missionary schools to teach reading, writing and religion to young Africans in the newly written dialect.

In my job market paper, I evaluate the persistent effects of Bible translation on modern education and child health outcomes, two areas of focus of historical missionaries. The presence of Protestantism more generally has been linked to improvements in female education in particular, both in Europe and in Africa. The Protestant insistence that both women and men should be able to read the Bible has been argued to have been a major factor in female education. With more educated mothers, one can also expect healthier children.

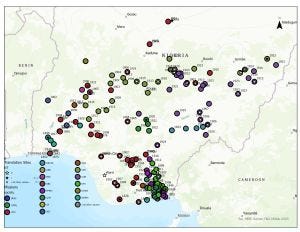

Analyses using existing missionary data on Africa (e.g., Cagé & Rueda 2016) have been able to show that missionaries had long-term effects, but richer data is needed to understand why. To this end, I construct two novel datasets on Bible translations and missionary activity in Africa. Information on the timing and number of translated Bible verses comes from the Ethnologue and the Book of a Thousand Tongues. In addition, I hand-code the site of translation from biographical information for over 300 missionary translators from over 500 sources. In broad strokes, the site of translation is the location where the main Bible translators were stationed at the time of translation.

I digitize missionary data from three Protestant missionary atlases (Beach 1903, Dennis 1911, Beach 1925) and two Catholic ones (Streit 1913, Streit 1929). The resulting data is global in coverage, linked and panel, with improved geographic precision, fewer missed stations and information on missionary society and infrastructure. I restrict my sample to Bible translations started before 1935 for a better match with the missionary data.

I combine these newly digitized datasets with Demographic and Health Surveys from 33 African countries. To assess the spatial variation in the effects of Bible translation, I use a 0.25 by 0.25 decimal degree grid of Africa. I include a host of geographical, historical and missionary controls to account for the fact that missionaries settled in more central, prosperous areas (Jedwab et al., 2022). That is, I compare grid-cells with similar histories of missionary activity but with varying levels of Bible translation. I find that a grid-cell with a New Testament – a common stopping point – translated before 1935 is associated with 2.1 percentage points higher literacy and 0.15 more years of schooling. It is also associated with 0.09 fewer children per family, 2.5 percentage points lower likelihood of stunting among children and 1.7 percentage points lower likelihood of a child being underweight.

To address the possibility that missionary translators strategically chose languages with more speakers, I develop an instrument that relies on the proclivity of missionary societies to translate scripture throughout the world. The Baptist Missionary Society, for example, translated the Bible into many languages in northeastern India before ever establishing itself in Africa. I find these global proclivities to be highly predictive of local activity with a first stage F-statistic hovering around 30. Two-stage least squares results are even larger in magnitude than OLS ones.

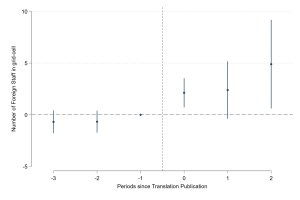

These results show that effects of missionaries were much more pronounced in areas with Bible translations than those without. It remains to understand why. Thus, I find that the most immediate effect of Bible translations was not actually on local African populations, but on foreign missionaries themselves. Indeed, a translated Bible meant a familiar book that missionaries could use for language learning (Vilhanova 2011). Using the panel nature of the missionary data, I conduct a matched event study comparing two sets of grid-cells both containing missionaries but with and without Bible translations. I find an increase of 5 foreign missionaries as a result of the publication of the first Bible verses. The number of medical missionaries also increased, suggesting that Bible translations also enable investments outside education. Further, I provide evidence that these missionaries made key investments in education and health infrastructure such as high schools, printing presses and even hospitals. I also provide some evidence for the persistence of this infrastructure to modern times.

Finally, I find that languages in which there was Bible translation are more likely to be used as a medium of instruction in schools. Indeed, translated Bibles meant the codification of language which is a major step towards use in schools. Moreover, improvements in education are focused among those whose language is used as a medium of instruction. Improvements in child health, however, are spread more evenly across all language groups.

In sum, my paper sheds light on the implications of one of the most important roles filled by missionaries: language pioneers. Bible translations created bridges of communication. These bridges gave African populations access to reading and writing in their mother tongue. In turn, they gave foreign missionaries access to the languages of Africa. With this insight, I shed some light on why missionaries had persistent effects in some areas but not others, what the basis of for difference is and which African populations benefited most from missionary presence.