Extractive Taxation and the French Revolution

by Tommaso Giommoni, Gabriel Loumeau and Marco Tabellini

The French Revolution was a watershed moment in world history. In just a few years it dismantled a centuries-old political order, recast citizenship and sovereignty, and propelled ideas about rights and representation across Europe. Although the causes were many, taxation has long been singled out as central (Noberg, 1994; Touzery, 2024). As Alexis de Tocqueville put it, allowing monarchs to tax without consent “sowed the seed of practically all the vices and abuses” that undermined the regime (Tocqueville, 1856). Yet, despite the prominence of this idea in historical narrative, systematic evidence linking fiscal burden to popular unrest has been limited.

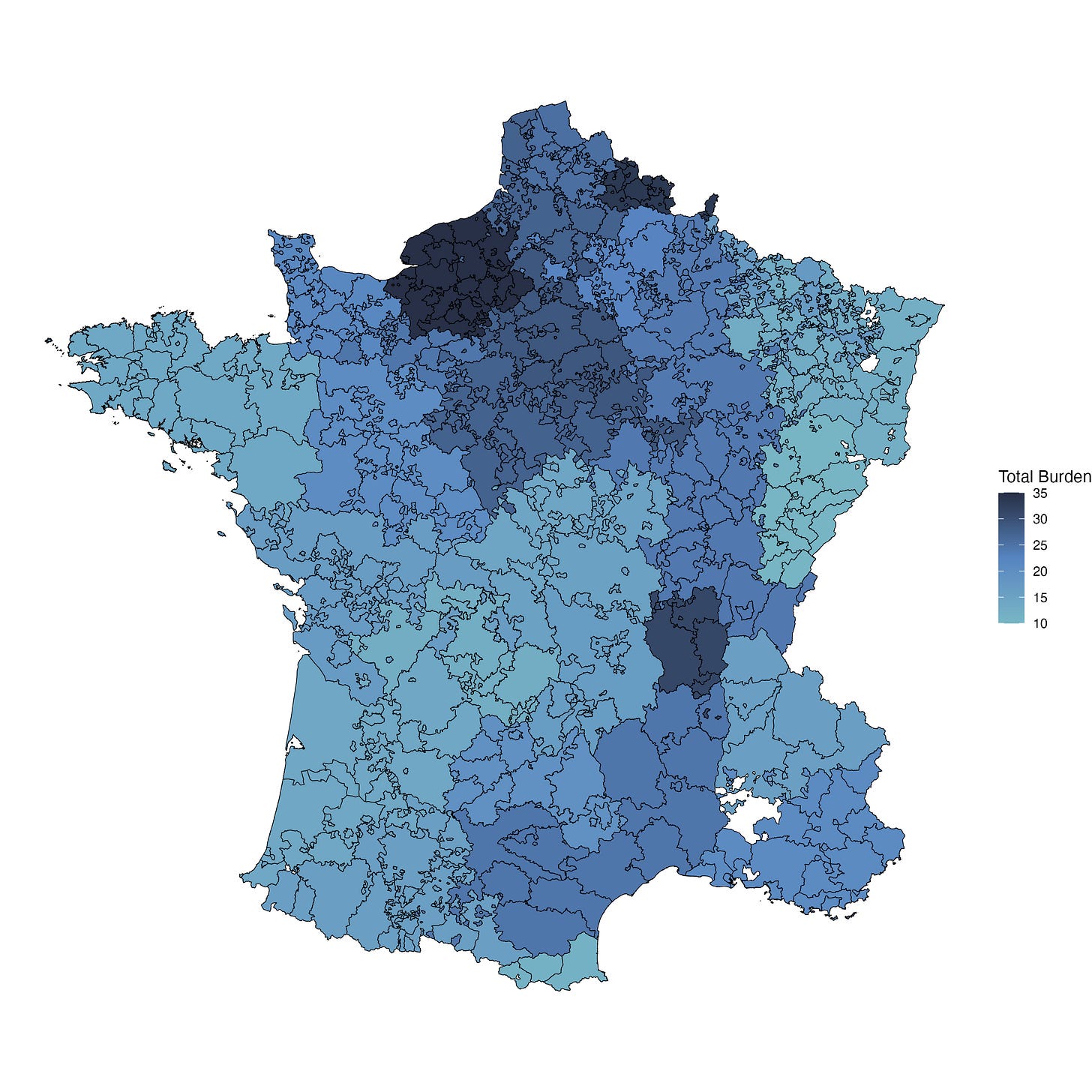

Our new paper, Extractive Taxation and the French Revolution, tests this hypothesis with newly digitized fiscal and unrest data. We geo-reference bailliage-level measures of per-capita tax burden circa 1780 assembled from Touzery (2024), and map the substantial spatial variation in that burden (Figure 1). We merge those measures with the HiSCoD catalogue of riots assembled by Chambru and Maneuvrier-Hervieu (2024) to ask whether areas bearing heavier fiscal loads experienced more popular revolts in the decades leading up to the French Revolution.

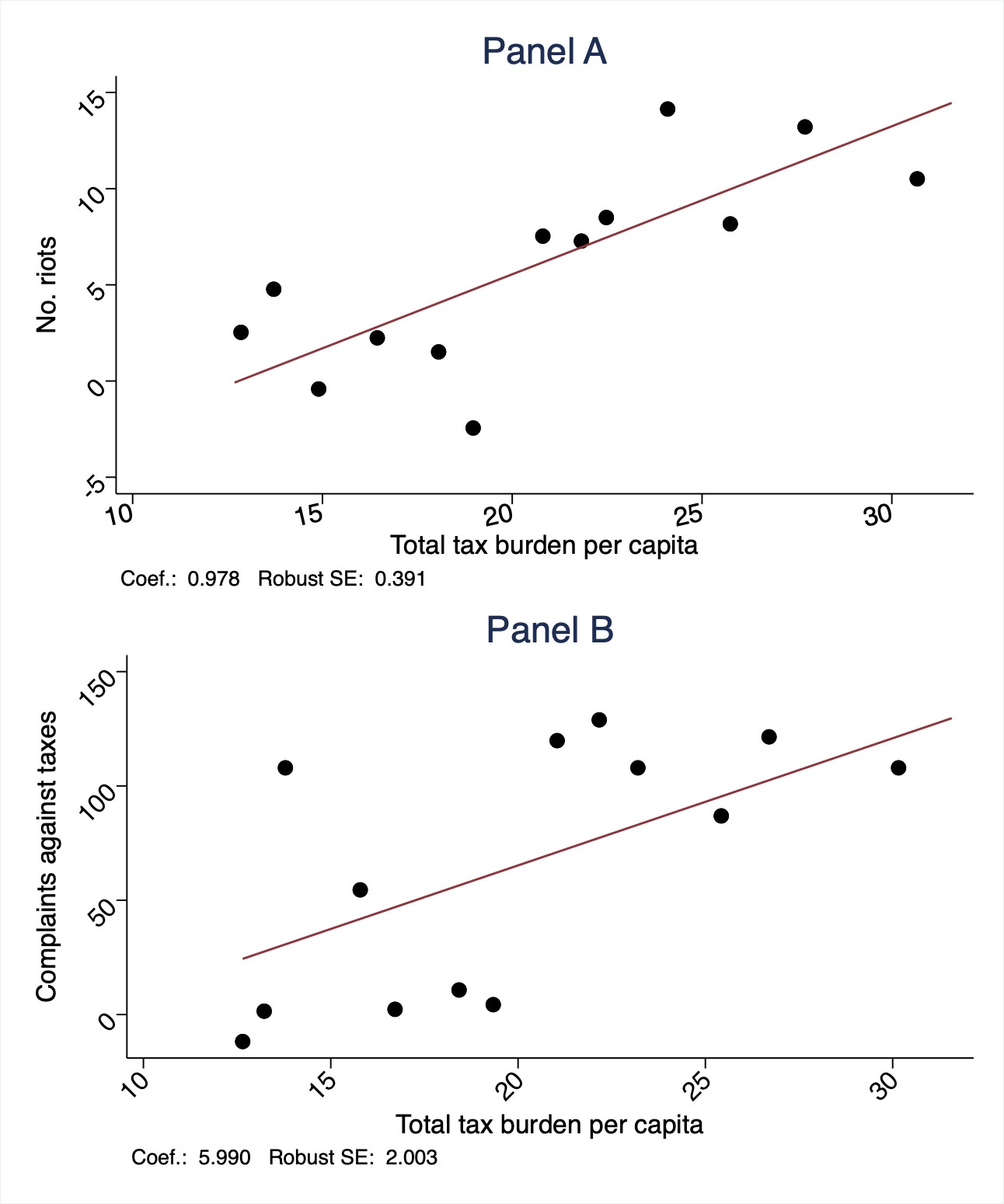

Figure 2, Panel A, plots a simple binscatter and illustrates the basic relationship: bailliages with higher per-capita taxes had more riots between 1750 and 1789. The association is robust to controlling for several factors commonly linked to pre-revolutionary and revolutionary unrest. Moving from a bailliage in the bottom quartile of the tax-burden distribution to one in the top quartile (about an 8% share of per-capita income at the time) more than doubles the number of riots in 1750–1789. We interpret these patterns as evidence of broad opposition to taxation. To probe the mechanism, we turn to the cahiers de doléances (literally, the lists of grievances) compiled ahead of the Estates General in the spring of 1789. Figure 2, Panel B, shows that bailliages with heavier tax burdens submitted more complaints about taxation. Notably, these complaints emphasized not only the economic burden of taxation but also its unequal incidence across social groups and territories and its extractive character.

Historical accounts emphasize that indirect taxes were especially resented (Sands and Higby, 1949; Touzery, 2024). Administered through a dense fiscal infrastructure of warehouses, checkpoints, and inspections run by the Ferme générale, these levies were highly visible in everyday transactions. The salt tax gabelle—given the state monopoly over a basic necessity—and the traites—which fragmented internal trade through tolls and inspections—were widely viewed as particularly oppressive, and their borders often reflected centuries-old bargains rather than economic fundamentals. Consistent with this view, indirect taxes drive our results: when we decompose the overall tax burden, the indirect component is the strongest predictor of both riots and tax-related complaints.

This motivates a quasi-experimental strategy exploiting sharp discontinuities in the salt tax and the traites, where neighboring municipalities faced markedly different indirect tax regimes. We find that crossing the border from a low- to a high-tax municipality increases the number of riots. The effects begin to emerge in the 1760s, and become larger and more precise over time, peaking in the 1780s. Crossing the tax frontier roughly doubles the number of riots between 1780 and 1789. Consistent with our interpretation, the effect is driven entirely by tax-related riots, while we find no discontinuities for unrest unrelated to taxation, such as food or labor riots.

One interpretation of these findings is that taxation created latent conditions for unrest, which were activated by broader political and economic forces. One such force was the spread of Enlightenment ideas about equality and justice (Darnton, 1982; McMahon, 2001). Consistent with this view, the effect of crossing a tax border is larger where tax gaps are greater and along borders with stronger diffusion of Enlightenment ideas, where fiscal inequality would have been more salient. A second trigger was economic distress driven by adverse weather shocks in the late 1780s (Lefebvre et al., 1947; Waldinger, 2024). Poor harvests raised wheat prices and strained household budgets, especially in heavily taxed areas. Combining the RD design with spatial and temporal variation in temperature shocks, we find that a 10% increase in summer temperature (about 1.8°C) roughly doubled the number of riots in high-tax municipalities relative to their low-tax neighbors.

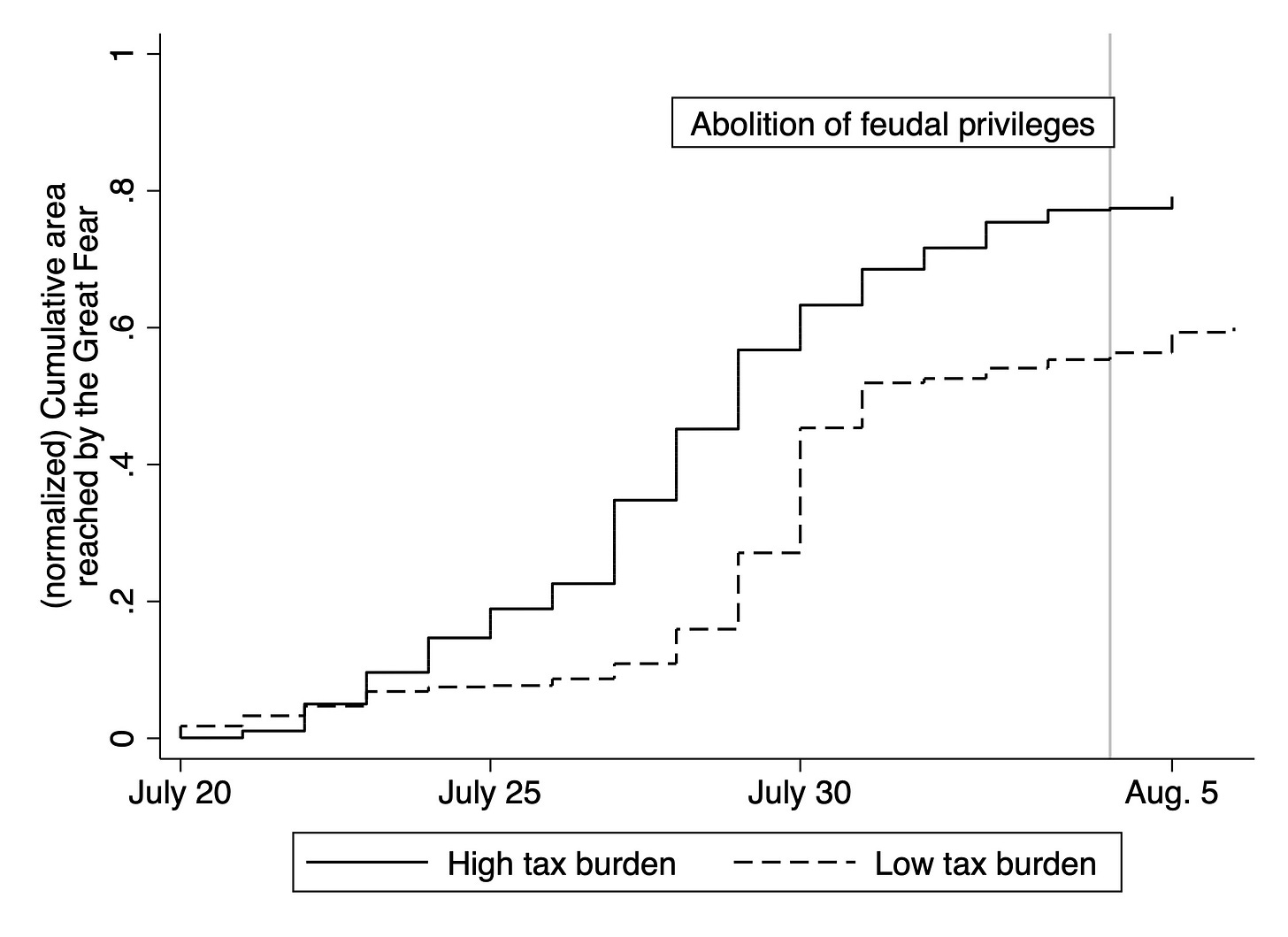

Local grievances can generate isolated disorder; if they spread, they can fuel revolutionary upheaval. To assess whether fiscal discontent shaped this transition, we study the Grande Peur (Great Fear) of July–early August 1789 (Lefebvre, 1973). Following the fall of the Bastille, rumors of aristocratic plots swept rural France, triggering attacks on manor houses and the destruction of feudal records, and culminating on August 4 with the abolition of feudal privileges. Tracing the spatial diffusion of this panic, Figure 3 shows a clear divergence: high-tax bailliages were reached earlier and experienced faster spread. By August 4, a substantially larger share of high-tax territory had already been affected, and by the end of the episode roughly 80% of high-tax areas had been reached, compared with about 60% of low-tax areas. Our formal analysis confirms that high-tax bailliages were more likely to ignite panic contagion and experienced earlier and more extensive spread overall.

These patterns suggest that fiscal grievances fueled the revolutionary crisis from below. But did taxation also shape the Revolution from above, through the behavior of its political representatives? To answer this question, we analyze more than 60,000 speeches from the Archives Parlementaires, delivered between May 1789—when the États Généraux convened—and January 1793, when Louis XVI was executed. Deputies from high-tax constituencies engaged very differently with fiscal issues than their counterparts from low-tax areas. They were about 60% more likely to speak about taxation, nearly twice as likely to criticize the Ancien Régime, and roughly 60% more likely to defend the Revolutionary project in tax-related speeches. Their rhetoric also framed taxation more often as unequal or oppressive and more frequently called for fundamental fiscal reform.

We then move beyond fiscal debates to examine how taxation shaped political behavior at key turning points of the early Revolution. In the weeks following the Great Fear—when the Assembly was actively debating the future of the regime—deputies from high-tax constituencies were more likely to demand institutional change, explicitly call for the abolition of feudal privileges, and openly criticize the monarchy. Turning next to the Assemblée Législative (October 1791–September 1792), we find that legislators from heavily taxed areas were more likely to support the abolition of the monarchy. Finally, using newly digitized roll-call votes from the Convention Nationale, we show that deputies from high-tax regions were also more likely to vote for the king’s execution in January 1793.[1]

Taken together, our findings suggest that taxation played a central role in the origins and dynamics of the French Revolution. More broadly, the results speak to a mechanism through which fiscal systems that rely on coercion and inequality can destabilize regimes. Future work could examine whether similar dynamics operated in other historical settings—such as Imperial Russia or late-Qing China—where extractive taxation coexisted with social inequality and political transformation, to assess how far these patterns travel across time and institutional contexts.

REFERENCES

Chambru, C. and Maneuvrier-Hervieu, P. (2024), ‘Introducing hiscod: A new gateway for the study of historical social conflict’, American Political Science Review 118(2), 1084–1091.

Darnton, R. (1982), The Literary Underground of the Old Regime, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Degrave, A. (2023), ‘Local rule, elites, and popular grievances: Evidence from ancien régime france’, Journal of Historical Political Economy 3(1), 1–29.

Lefebvre, G. (1973), The Great Fear of 1789: Rural Panic in Revolutionary France, Princeton University Press.

Lefebvre, G., Palmer, R. R. and Tackett, T. (1947), The coming of the French Revolution, Princeton University Press Princeton.

McMahon, D. M. (2001), Enemies of the Enlightenment: The French Counter-Enlightenment and the Making of Modernity, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Norberg, K. (1994), The french fiscal crisis of 1788 and the financial origins of the revolution of 1789, in ‘Fiscal crises, liberty, and representative government, 1450-1789’, pp. 253–298.

Sands, T. and Higby, C. P. (1949), ‘France and the salt tax’, The Historian 11(2), 145–165.

Shapiro, G., Tackett, T., Dawson, P. and Markoff, J. (1998), Revolutionary Demands: A Content Analysis of the Cahiers de Doléances of 1789, Stanford University Press.

Tocqueville, A. d. (1856), ‘The old regime and the french revolution’, New York (Original: L’Ancien Régime et la Révolution, Paris 1856).

Touzery, M. (2024), Payer pour le Roi. La fiscalité monarchique France, 1302-1792., Champ Vallon, Paris.

Waldinger, M. (2024), ‘“Let them eat cake”: drought, peasant uprisings, and demand for institutional change in the French Revolution’, Journal of Economic Growth 29(1), 41–77.

[1] Political authority during the Revolution was exercised through three successive national assemblies. The Assemblée Constituante (1789–1791) drafted the constitutional framework of the new regime; the Assemblée Législative (October 1791–September 1792) governed under the Constitution of 1791 until the fall of the monarchy; and the Convention Nationale, established after the monarchy’s abolition, ruled France from September 20, 1792, to October 26, 1795.

Tommaso Giommoni is an Assistant Professor at the Amsterdam School of Economics, University of Amsterdam, a Research Affiliate at CESifo, and a Research Fellow at the Tinbergen Institute. He is also affiliated with the Baffi CAREFIN Centre at Bocconi University. His main research interests lie at the intersection of Public Economics, Political Economy, and Economic History, with a particular focus on topics related to taxation, economic growth, and inequality.

Gabriel Loumeau is a full professor of Economics at the University of Neuchâtel, where he holds the Chair of International Economics. He is affiliated with the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and the CESifo research network. His research lies at the intersection of urban, regional, and international economics. He studies the causes and consequences of regional development, with a particular focus on how economic geography, infrastructure, and public policy shape patterns of growth, commuting, and inequality.

Marco Tabellini is an assistant professor in the Business, Government, and International Economy unit and is affiliated with the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). His research studies how international and internal migration reshape politics, society, and the economy, with a focus on when and why immigration generates political backlash, the conditions under which social integration succeeds, and how migration transforms societal boundaries in countries such as the United States. More broadly, his work in political economy examines how institutional outcomes and democratic processes are shaped by internal forces (such as taxation) and external forces (such as trade).

GREAT ARTICLE