History LLMs: Giving the Past a Voice with Large Language Models

by Daniel Göttlich, Dominik Loibner and Hans-Joachim Voth

Not long ago, history and machine learning seemed like fundamentally different worlds. Today, these worlds are merging in ways that would have seemed quite unlikely until recently, and thus are even more exciting. The release of ChatGPT almost three years ago marked a turning point. What initially introduced LLMs to a broad audience quickly proved to be relevant for the academic community as well, spreading rapidly across disciplines in both the natural and social sciences, including history.

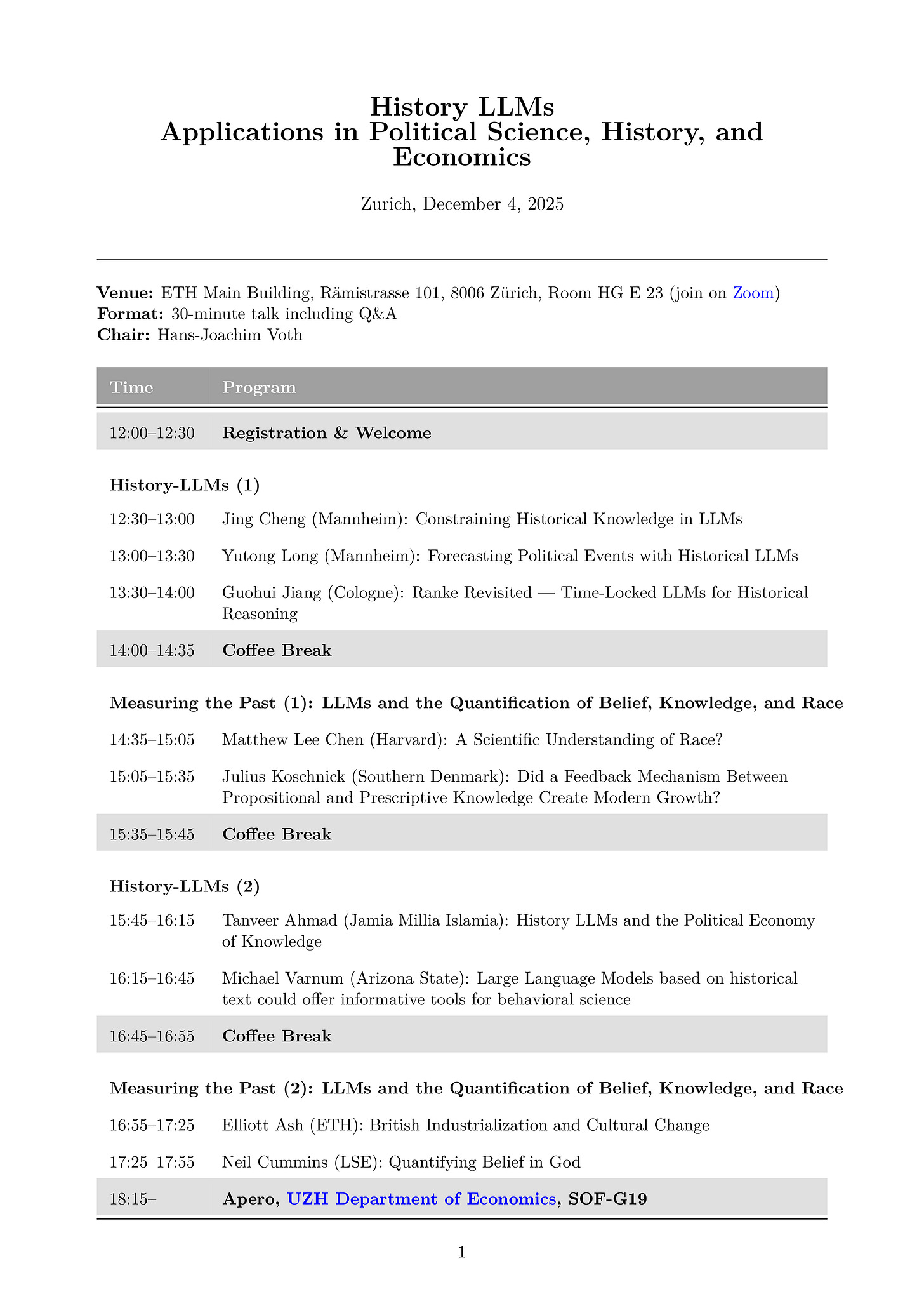

With this in mind, we organised a Workshop on History LLMs at the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich in early December. The workshop brought together a wide range of researchers from history, economics, and computer science (CS) to reflect on the current state of the field and to discuss where it may be heading.

The more than 40 applications we received highlighted the strong and ongoing interest in the topic and its resonance within the field, reinforcing our view that the workshop content closely mirrored the broader intellectual landscape.

The submissions and discussions revolved around three key themes:

Using LLMs to measure and quantify the past

Conceptualising History LLMs, what is a History LLM and what makes them distinct

Implementing History LLMs in practice

1. Measuring and Quantifying the Past with LLMs

One of the most immediately useful and widely adopted uses of LLMs in economic history research is as highly capable research assistants. LLMs can process vast quantities of text at scale. They do so consistently and with few restrictions on language. Using “helpers” at such a scale would be infeasible or unaffordable using human labor.

Historians and social scientists use LLMs to:

Extract information from large text corpora

Generate summaries or classifications

Explore potential analytical avenues

In this sense, LLMs augment human labour. They do not replace researchers, but they dramatically expand what an individual researcher or small team can accomplish. The early narrative around productivity gains might have been overly optimistic, sometimes suggesting that LLMs could function as fully autonomous research assistants or even digital clones of researchers. This is arguably exaggerated. However, we are already living in a period where scholarly manpower is significantly amplified by LLM-based tools.

Recent work presented at the workshop showed how LLMs are used to transform unstructured historical sources into quantitative evidence.

Koschnick shows how transformer-based language models can operationalise innovation and knowledge spillovers by measuring semantic novelty and cross-field similarity in publication titles and patents from 1600–1800, directly testing Mokyr’s theory of a feedback loop between propositional and prescriptive knowledge.

Chen, Duffy, and Weigand use contextualised transformer embeddings to recover and quantify distinct historical meanings of “race” in British scientific writing, tracking shifts between biological, analytical, and social conceptions over the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries without imposing modern categorisations.

Ash and Xue apply LLMs to interpret and classify historical proverbs, enabling the measurement of cultural values such as work ethic, individualism, and innovation across regions and over time during the British industrialisation.

Cummins and Noble use LLM-assisted pipelines to extract religious language and economic information from United Kingdom wills spanning 1300–1850, quantifying long-run changes in sincere versus nominal religiosity.

Together, these studies show how LLMs function as scalable tools for measuring beliefs, culture, and knowledge production in the past. The sheer scale of applications, categorizing complex concepts quickly and at scale, dramatically expands what researchers can accomplish using text.

For historical research, this means that phenomena once considered too large, too dispersed, too complex, or too text-heavy can now be studied systematically. Quantification, pattern detection, and large-scale text analysis are becoming standard components of researchers’ toolkits.

2. Conceptualising History LLMs

While commercial LLMs are powerful, they face a fundamental limitation for historical research: they cannot forget. Once trained, the weights of a model are fixed. While they can be retrained using fine-tuning and similar techniques, LLMs inevitably encode knowledge of later events because they are trained on modern corpora. No prompt, nor even the most advanced prompt engineering, can fully remove this hindsight bias. In the language of CS, modern-trained LLMs are “contaminated” with a knowledge of what is to come later.[1]

A similar problem is faced by historians themselves. A historian studying the Munich Agreement in 1938 cannot un-know the Holocaust and World War II, and neither can a modern LLM. This “curse of knowledge” fundamentally limits our ability to reconstruct how past actors understood uncertain futures.

Varnum et al., however, point toward an exciting solution. They argue that LLMs can become powerful tools for historical social science if they are carefully constrained. History LLMs can be understood as language models trained on historical corpora that encode the cultural, psychological, and normative patterns of past societies. Crucially, their distinctiveness lies in temporal specificity: a true History LLM reflects the mental worlds embedded in historical texts only up to a clearly defined cutoff point and therefore differs systematically from modern LLMs trained on contemporary data.

Ahmad highlights important caveats that accompany the training of History LLMs by situating them within the political economy of knowledge. He argues that History LLMs are shaped by asymmetries in archival survival, digitisation, language dominance, and AI infrastructure. As a result, they are never neutral reconstructions of the past. Rather, they constitute algorithmic condensations of historically contingent archives and therefore carry the risk of reproducing colonial, geopolitical, and epistemic hierarchies.

For historians, such History LLMs resonate strongly with long-standing methodological traditions. Collingwood emphasised the importance of reimagining past thought, while economic historians such as Robert Fogel used counterfactual reasoning to understand historical causality. LLMs offer a novel way to operationalise these approaches. Unlike traditional models with rigid assumptions, LLMs learn complex patterns of reasoning, language, and cultural nuance directly from text.

Projects such as MonadGPT and StoriesLM represent important early steps toward using LLMs to model historical reasoning. However, in our view, these efforts do not yet come close to realising the full potential of LLMs for historical knowledge production and counterfactual reconstruction.

3. Implementing History LLMs

Implementing History LLMs is both technically and conceptually demanding. Doing so requires several key ingredients:

Carefully curated and temporally bounded training data

Explicit enforcement of historical knowledge cutoffs

Systematic evaluation of historical accuracy, recall, and anachronism

While discussion around such models has circulated for some time and again gained considerable momentum recently[2], research presented at the workshop demonstrates that these ideas are rapidly moving from conceptual proposals toward concrete implementations.

Researchers from the University of Mannheim and our team in Zurich presented approaches to training History LLMs with the aim of reconstructing historical belief spaces, forecasting elections, and analysing political or cultural reasoning without contamination from later events.

One approach, presented by Cheng, Kranz, and Ahnert, combines curated historical corpora with prompting strategies that assign models a temporal identity. This is supported by validation layers designed to detect anachronistic information and enforce cutoff years. While this strategy goes beyond naïve prompting, it still relies on post hoc controls rather than fully eliminating future knowledge from the model. As a result, the next step the team aims to take is to train their own base model on time-restricted historical data.

A hurdle already tackled in the work of Göttlich et al. through the training of their own history LLM, Ranke-4B[3]. Rather than relying primarily on prompting strategies, they pretrain and fine-tune language models exclusively on texts available prior to specific historical cutoff dates. These time-locked models more reliably reproduce period-specific beliefs, uncertainties, and normative judgments, thereby reducing anachronistic contamination and better approximating the informational horizons faced by historical actors.

Detailed results and training specifications for the University of Zurich model-family, Ranke-4B, are documented in our public GitHub repository, which will soon outline the full training pipeline, validation strategy, and model design choices. Additional updates and results will be added gradually in the near future.

Across approaches, effective implementation hinges on careful benchmark design, rigorous validation against historical knowledge constraints, and a balance between computational feasibility with historical fidelity.

When trained exclusively on temporally bounded corpora, History LLMs offer something genuinely new: scalable and systematic tools for reconstructing historical “thought worlds.” They allow researchers to explore how people in the past might have reasoned under uncertainty, without importing modern hindsight into historical analysis.

Looking Ahead

In 1985, Steve Jobs speculated that one day software might allow us to “ask Aristotle a question and get an answer.” What once sounded like science fiction now seems within reach.

History LLMs are not replacements for historians. However, they represent a new set of tools and instruments that can deepen our understanding of the past, allowing us to scale long-standing historical research in new ways. They also hold out the promise of extending measures of attitudes and beliefs backwards in time, in a rigorous and quantifiable way, through the training of time-locked LLMs.

The Zurich workshop made one thing clear: the field is moving fast, but the most exciting work lies ahead. Measuring the past, conceptualising historical reasoning, and implementing time-locked models are all steps toward a new kind of historical inquiry.

[1] See e.g. Jens Ludwig, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Ashesh Rambachan, “Large Language Models: An Applied Econometric Framework,” NBER Working Paper 33344 (2025), https://doi.org/10.3386/w33344.

[2] See e.g. recent X contributions by @Teknium, @victormustar and @JonhernandezIA.

[3] Leopold von Ranke: „wie es eigentlich gewesen“ [how it actually was]

Daniel Göttlich is a Predoctoral Fellow at the University of Zurich with a particular interest in applying machine learning and language modelling to historical data. His research lies at the intersection of political economy, economic history, and cultural economics.

Dominik Loibner is a Research Fellow at the University of Zurich, working at the intersection of cultural economics, political economy, and economic history, with a focus on large-scale historical data and the application of machine learning techniques.

Hans-Joachim Voth is UBS Foundation Professor of Economics at the University of Zurich and Scientific Director of the UBS Center for Economics in Society. His research spans economic history, political economy, and cultural economics, with growing applications of computational social science. He has contributed extensively to research on Europe’s long-run economic development. His work also examines cultural persistence and change, including national identity, social networks, and extremist ideology, and more recently applies vision AI to large-scale U.S. yearbook data to study long-run trends in individualism.

Brilliant breakdown of temporal specificity in model training. The hindsight contamination problem you outline is genuienly understated in most LLM applications to historical analysis. I actually tested a similar concept with local pre-1940s newspaper corpora last year and the diffrences in forecasting ability vs modern models were pretty stark. What's particularly intersting about Ranke-4B is that it could let us test counterfactuals with belief structures that actually existed rather than retro-fitted ones.