How Colonialism Changed the World — for Better and for Worse

The death of Queen Elizabeth II produced a record number of hot takes on the British Empire, most notable only for what they revealed about the ideology of the author. That of Fox news host Tucker Carlson was no exception:

“When the British pulled out of India, they left behind an entire civilization, a language, a legal system, schools, churches, and public buildings, all of which are still in use today…Today, India is far more powerful than the UK, the nation that once ruled it, and yet, after 75 years of independence, has that country produced a single building as beautiful as the Bombay train station that the British colonialists built? No, sadly, it has not. Not one.”

But colonial nostalgia is hardly confined to the far right. South African Democratic Party leader and anti-apartheid activist Helen Zille was disciplined by her party after tweeting that “For those claiming legacy of colonialism was ONLY negative, think of our independent judiciary, transport infrastructure, piped water etc.” Chinese dissident and Nobel Peace prize laureate Liu Xiabao went even further in a prescriptive direction, arguing that to make China a democracy would take “300 years of colonialism. In 100 years of colonialism, Hong Kong has changed to what we see today.”

These opinions are less unmoored from the scholarly consensus than they might seem. Using historical wind patterns as an instrument, Feyrer and Sacerdote (2009) find a” robust positive relationship between the number of years spent as a European colony and current GDP per capita.” Similarly, in their classic 2001 article, Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson argue that the key to economic growth outside of Europe is the implantation of good institutions, a result best achieved by settler colonialism with comprehensive population replacement. Mattingly (2017) similarly argues that “Japanese colonization of northern China had a positive long-run effect on state institutions—with persistent increases in schooling, health, and bureaucratic density.”

More broadly, “state capacity,” “state building,” and “strong institutions” have been widely touted as the solutions to any number of political, economic and social problems in developing countries, and formal state institutions generally became larger and more powerful under colonial regimes—in fact, in some places colonial states were the first states of any kind. How is it possible to condemn anything which brought the world the political economy equivalent of motherhood and apple pie?

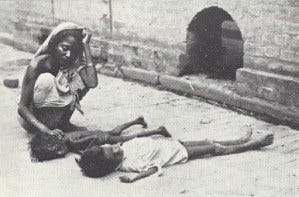

However, those who believe colonialism to be unequivocally negative and evil have several more or less unanswerable arguments on their side. After all, a simpler way of describing “comprehensive population replacement” is genocide, and colonialism was built on the back of any number of incidents of mass murder, to say nothing of epidemics and famine deaths to which colonial states were indifferent. One wonders, for instance, if the Indian government would have responded more forcefully to the Bengal Famine of 1943 (in which at least 3 million people died) if it had had reported to somebody other than Winston Churchill, who thought the Bengalis brought it on themselves by “breeding like rabbits.” More simply, why should an institution that was more or less unapologetically designed to enrich Europe at the expense of the rest of the world have benefits for the rest of the world? Critics and defenders of colonialism usually talk past each other because they are evaluating four fundamentally distinct counterfactual worlds.

No Great Divergence: That Western Europe did not develop a technological advantage over the rest of the world in the early modern period.

No Political Expansion: That Western Europe did develop a technological advantage, but kept its relationship with the rest of the world strictly economic and cultural.

Informal Empire: That Western Europe did expand politically, but confined its role to trading ports or informal zones of influence, as it did in 17th century India or 19th century China.

Non-European Colonialism: That some other region (perhaps East Asia) developed a technological advantage over the rest of the world and colonized.

This is to say nothing of the large and flourishing literature comparing the fates of regions colonized by different European powers (Lee and Schultz 2012, Lee and Paine 2019a, Lange, Mahoney, and Vom Hau 2006), parts of colonies with more or less indirect patterns of domination (Iyer 2010, Lee 2019), different social groups within countries (Lee 2017),or countries before and after decolonization (Lee and Paine 2019b).

Let us take these four counterfactuals in turn.

No “Great Divergence:” This is perhaps the most difficult of the counterfactuals to analyze, given that it is an attempt to think about what modern history would look like without industrial modernity as we understand it. A world without European economic expansion would be a world without the Columbian exchange of germs, encomiendas and the Atlantic slave trade, but it would also be a world without the Columbian exchange of food crops, antibiotics, and (quite probably) liberal democracy. Reasonable people can disagree about how to assess this tradeoff. In part because I have owed my life on several occasions to modern medicine, I have always thought the Faustian bargain of modernity to be one worth taking. While the sadness and wasted potential of children dying in infancy or a large section of humanity spending much its time spreading manure is less historically visible than the millions killed or subordinated by colonialism, they are just as real, and, in the long run, probably more damaging.

2. No Political Expansion: This counterfactual is perhaps the most unlikely of the four—it is difficult to imagine how the elite on any continent with clearly superior military technology could have resisted the temptation to use it on the rest of the world. However, if they had done so, indications are that the world would be a more equal place. Revealingly, the non-western nation most able to keep its relationship with the West purely economic, Japan, has also been the most successful non-western nation by conventional human development measures. This would also fit with the general condemnation of the specifically extractive aspects of colonial states (Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson 2002, Dell 2010), and the generally positive assessment of the effects of cultural interventions like missionary education (Castelló‐Climent, Chaudhary, and Mukhopadhyay 2018) and railroads (Donaldson 2018) as distinct from colonial rule. Note that even in this world there would still have been mass deaths from the spread of Eurasian diseases, and it is likely that contact with European military technology would have catalyzed a process of violent statebuilding, similar to those that occurred in early 19th century Africa.

3. Informal Empire: Unlike the two previous counterfactuals, we can actually observe areas of the world and periods of history that were subject to informal empire—China, Thailand, coastal Africa before the 19th century, and coastal South Asia before the 18th. Unfortunately, two problems confound causal reasoning. Firstly, the areas that were not colonized were not randomly selected; generally, they were able to resist colonialism because of a relatively high level of political stability and legitimacy. Secondly, one must carefully differentiate the effects of informal empire on the small area around European trading posts from their effect of the broader region. While the effect on the trading posts might be positive (see Gaikwad 2014 on India, or any work on the political economy of Hong Kong), the broader effects might well be negative (see Nunn 2008 on the African slave trades).

However, it is worth noting that the most plausible paired comparisons tend to indicate that informally colonized areas are now much richer and more stable than their formally colonized neighbors. According the Maddison estimates, for instance, Thailand had a GDP approximately 13% higher than Myanmar before colonialism in 1820, and approximately 509% higher today. Similarly, Turkey was 49% richer than Algeria in 1820, but is 154% richer today even after Algeria’s oil discoveries.

Non-European Colonialism: Virtually any opinion on the question of whether other parts of the world would have “done colonialism” better or worse than Europe is likely to become mixed up with untestable prejudices of various kinds—that “enlightenment values” made European rule relatively benign, or that racial prejudice made it uniquely dangerous. Moreover, it is likely that the experience of industrial growth and imperial expansion would have changed the culture and political economy of any putative non-western colonizer beyond recognition. I, however, am personally skeptical that the evils inherent in imperialism vary much from perpetrator to perpetrator. In particular, the incidents of non-western imperialism that we have been able to observe over the past three centuries (China in the far west, Ethiopia in its non-Amhara borderlands, and the Ottoman Empire in the Caucasus and Balkans) were (and are) difficult to distinguish from the actions of Western colonizer in their ruthless use of violence and pronounced ethnocentrism.

I often tell students that “history does not give us do-overs.” Colonialism, in particular, is unlikely to do us this favor. A major macro-phenomenon closely associated with other major macro-phenomena, it changed the world so comprehensively that it left room for little of the cross-sectional variation beloved by social scientists. The importance of the question, however, means that this question will always be one of the most important, indeed foundational, puzzles of historical political economy.

Huh? You said a bunch of nothing.

Huh? You said a bunch of nothing.