How Medieval and Early Modern Monarchies Cheated Death

By Andrej Kokkonen & Anders Sundell

“In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes” wrote Benjamin Franklin. Taxes have certainly received considerable attention in the study of historical political economy. War made the state, states made war, and to make war, states need money.

But Franklin’s other certainty, death, has remained strangely absent from discussions of political development. That is puzzling, given how central longevity is to state building.

Modern, democratic political systems consist of a web of interlocking institutions that both reinforce and check each other’s power. Even though there is a head of government, there is also a legislature to write laws and pass budgets, courts to check the legality of laws and decrees, central banks that control monetary policy, government agencies with regulatory powers, and so on. When there is a change of leadership in one institution, the others continue to operate, keeping the web intact.

An autocratic system, where power flows from one person at the top, is different. Instead of a web, it is an arch, where the ruler is the keystone that holds it all together. Remove it, and the rest of the arch will crumble. L’Ètat, c’est moi.

The inescapability of death

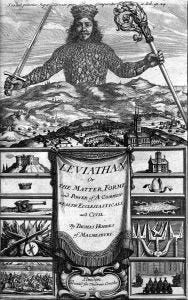

Thomas Hobbes, who above all others espoused the idea of unchecked sovereignty, understood the problems this caused for the durability of the state, and political stability in general. The cover of Leviathan shows a king towering over the land, his body made up of small persons. For Hobbes, the image of society as a body whose head is the monarch primarily served to show the validity of sovereignty – the head must be in charge. But it also illustrates the contradiction between the necessity of eternal institutions and the unavoidable mortality of the flesh:

“Of all these forms of government, the matter being mortal, so that not only monarchs, but also whole assemblies die, it is necessary for the conservation of the peace of men that as there was order taken for an artificial man, so there be order also taken for an artificial eternity of life; without which men that are governed by an assembly should return into the condition of war in every age; and they that are governed by one man, as soon as their governor dieth. This artificial eternity is that which men call the right of succession.” (Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan 1651, 119)

History shows how time and again polities were rattled or even broke down due to crises of succession. Famous examples include the Norman invasion of Britain 1066, where both William the Conqueror and Harold Godwinson claimed to be the true heir to the throne; The Hundred Years’ War (1337), caused by dispute over whether the throne could be inherited through a woman; the Wars of the Spanish (1701), Polish (1733) and Austrian (1740) successions, and so on and so forth. A civil war of succession also hastened one of the most spectacular collapses of empire in history: When Pizarro invaded the Inca Empire in 1531, two brothers of the last emperor were embroiled in a fight for the throne, which Pizarro exploited.

Modern scholarship has noted the need for institutions that outlive and transcend their individual office-holders. For instance, Joseph Strayer argued that their emergence was “a key point in state-building”. Similarly, Douglass North, John Wallis and Barry Weingast wrote that successful states must become a “perpetually lived organizations”. However, they did not specifically discuss how this perpetual life can be achieved, nor which institutional arrangements for the succession are most conducive to it.

Better a bad sultan than no sultan

In our new book (cowritten with Jørgen Møller), The Politics of Succession, published by Oxford University Press, we argue that hereditary succession through primogeniture – letting the oldest child (normally also restricted to sons) inherit – was a reasonable compromise solution to several problems bedeviling the succession.

The obvious drawbacks of hereditary succession is that it is a poor mechanism for selecting competent rulers. As Mancur Olson noted, there is a “near-zero probability that the son of a king is the most talented person for the job”. But he – and we – also concludes that uncertainty about the succession is a worse problem, as it might lead to civil strife. 11th century philosopher Al-Ghazali said that “the tyranny of a sultan for a hundred years causes less damage than one year’s tyranny exercised by the subjects against another.” (cited here) The limited discretion in ruler selection that comes from tying the succession to biology is a feature, not a bug. As long as the monarch has living sons, elites can easily predict who the next ruler will be, and coordinate their efforts to uphold the regime around him.

In the empirical chapters of the book, we show that in a sample of 27 European monarchies in the period 1000-1800, primogeniture succession was associated with fewer civil wars at moments of succession, fewer coups and depositions, and longer ruler tenures and dynasties.

Alternative (but common) principles of succession in the form of elective monarchy and brother inheritance had other advantages, such as producing adult monarchs that were readier for battle. This was likely important in earlier periods, but in the medieval and early modern world, the relative stability offered by primogeniture succession meant that it outcompeted alternative principles. Most states either switched (for instance France, England or Sweden), or disappeared (Poland and the Byzantine Empire).

Yet another effect of the Catholic Church

Many monarchs actively pushed to introduce primogeniture, but there were also structural preconditions that made adoption of the principle especially likely in Europe. The main driver of this was the Catholic Church. As recently described by our coauthor Jørgen Møller on this blog, the church affected European society profoundly, in a myriad ways. One of the more important transformations was the regulation of marriage, and requirement of monogamy.

The “normal” mode of inheritance tends to be that the patrimony is split between all heirs, and that applied to kingdoms as well. Primogeniture requires excluding all but one heir from the bulk of the inheritance.

When the church limited kings to having one wife at the same time (in contrast to, for instance, Ottoman Sultans), the number of potential heirs automatically decreased. In some cases, there was only one, which meant that primogeniture was the automatic outcome. Moreover, polygamy also leads to the potential for struggle between wives and their children about who of should take precedence in the inheritance. Monogamy simplifies the process – as long as there are living heirs, of course.

(Monogamy also increases the risk of dynasties dying out, which frequently happened. When the principle of primogeniture is fully developed, it is still possible to calculate the true heir. The British Royal Family lists the first 24 in the line of succession to the on their website, all the way down to the Queen’s one-year-old great-grandson Lucas Tindall. In the medieval period, this was of course much harder.)

We thus propose that the different principles of royal succession in the Christian and Islamic worlds might be another reason for the varying degrees of political stability observed by Lisa Blaydes and Eric Chaney. Islamic rulers of the period – including, famously, the Ottoman Sultans, remained polygamous, and did generally not adopt primogeniture. History could of course have taken another path. Max Weber thought that the fact that the Prophet Muhammed died without living sons was one of the great “historical accidents”. Had there been a son, he might have inherited Muhammed’s authority, thereby setting a precedent for primogeniture in the Islamic world.

A tale of two bodies

Hereditary succession is a system of seeming paradoxes. It is visceral at its core, bringing blood, birth, and death onto the main stage of politics. At the same time, when it succeeded, it also made the institution of the monarchy impersonal, allowing royal authority to be transmitted in a predictable manner for hundreds of years. As described by historian Ernst Kantorowicz, this paradox led to the idea of the king having two bodies, a mortal body natural and an immortal body politic.

Although democratic succession through elections have many superior features, its track record is still relatively short compared to the histories of hereditary royal succession. And as recent events in the United States have shown, the transfer of political power remain a thorny issue. States such as England and France managed to remain relatively intact for a millennium, with much weaker institutions. Understanding that staying power is a crucial scholarly task – and doing so requires significant attention to the issue of succession.