How Social Science History Changes Our View of the Ancient World: A Conversation with Josiah Ober

Growing up in Greece and having a love for history, I more than once considered pursuing classical studies. After my undergraduate degree, I even enrolled for one semester in the department of History and Archaeology of the University of Athens. But attracted by the breadth and the claims to generalizability of social science studies, I soon switched course and dropped out of Classics.

I probably would have stuck around for longer, if the description of the undergraduate program read something like this: “The department’s faculty approaches Classics from an interdisciplinary perspective that crosses geographical, temporal, and thematic territories. Studying ancient epic poetry can lead to looking at modern cinema afresh; ancient Athenian politics opens new perspectives on modern politics; and the study of Rome presents parallels with other empires just as Latin illuminates the history of English and the Romance languages.” The description comes from the Stanford department of Classics, where Josiah Ober, Professor of Classics and Political Science, is one of several people to continually push the boundaries of interdisciplinary research in the study of ancient history. In this post, we discuss his work on a new social science history of the classical Greek world, as well as other issues familiar to HPE scholars, like problems of data scarcity, and the challenging interaction between history and social science.

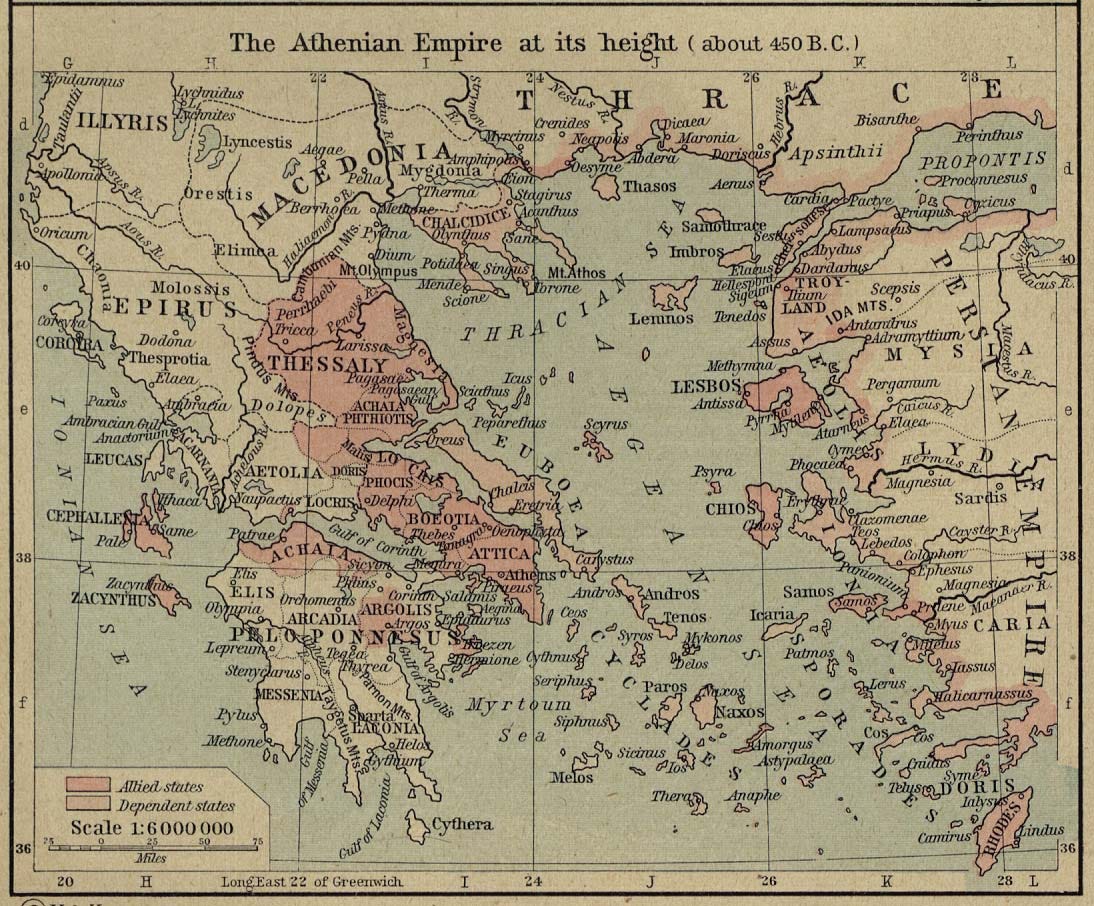

“Historians always have this dream of writing the big history, you know, the history of the whole thing,” says Josh Ober, who was trained as a historian. Given the dream is shared by many, histories of ancient Greece abound. Josh’s take on the ancient Greek world differs in an important way: it is an HPE treatment of the rise and fall of one of the major ancient civilizations, that relies on insights from rational choice theory and on a recent and, for the standards of the ancient world, massive dataset. “Some of my colleagues at Stanford, especially Ian Morris and Walter Scheidel, were working on a quantitative approach to ancient history, gathering bodies of archaeological data that in the aggregate were capable of saying something about economic change over time. And then, right around the same time, a huge inventory of classical Greek city states was published by a big team of Danish scholars containing basically everything we know about each city in standardized format in one great big book.”

The dataset, the Hansen/Nielsen Inventory of Archaic and Classical Greek City States, which was digitized by Josh and colleagues and can be browsed here, was the first step that led to the writing of his book, The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece. The second was the interdisciplinary push received by Josh during his stay at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) at Stanford, where fellows regularly and intensively interact across disciplinary barriers. “As a fellow at CASBS you are supposed to give a little pitch, and I said I am trying to explain why Athens was the most high-performing of all Greek city states. And someone immediately said ‘Well, how do we know?’ and I said ‘I’m a Greek historian, I am just telling you.’ And he said ‘That’s not a very good answer. Couldn’t you prove that somehow?’ And so I wondered whether I could use this big inventory of classical Greek city states that just appeared to put some data behind that.” The digitized inventory, together with archaeological data collected earlier by Ian Morris and new work on Greek demography, which provided information on the size of Greek populations from the time of Aristotle back to the end of the Bronze age, formed the body of evidence on which Josh Ober built his theory.

The combination of data and statistical inference pointed in the direction of high continuous growth in terms of both population and consumption from the 8th to the 4th century BC. This contradicted much of the received wisdom among classicists. “The standard story when I was growing up is that there really was no growth in antiquity, or the growth was so minuscule as to be irrelevant, and that what we really needed to explain was why was there no growth. Well, now it turns out we need to explain why there is growth.” The estimated growth was really dramatic. By measures of consumption and population density, Greece in the age of Aristotle looked something like 17th century Holland, the gold standard of a pre-modern economy before the industrial revolution. “So it’s not just growth, it’s a lot of growth. So now that becomes the thing to explain.”

Josh Ober relied on insights from rational choice theory to explain this growth pattern. Classical Greece was able to achieve and sustain high growth rates due to a culture of competition among a large number of small independent city states. This competition, though intense, was occurring within a setup of trade and cooperation, since the cities all formed part of a single cultural sphere. Competition within a system of cooperation drove innovation, not just in terms of technology, but also in terms of institutions. “The city state that devises institutions that allow cooperation at the highest level, and therefore allow for more capacity, is going to perform better. And because this is an ecology of states it is quite easy for states to learn from each other, so there is continuous emulation and continuous innovation, driving the whole ecology upward. Over time, one gets what looks like a continuous upward trend line.”

Given how radical was Ober’s reinterpretation of classical Greece, one cannot help but wonder why classicists had such a different picture of the ancient world until that time. “It’s partly because of one the most influential ancient historians of the 20th C, the great Sir Moses Finley. For one, Finley did not like archaeological materials and did not believe one can learn much from archaeology, which led him to ignore some of the evidence that could have suggested to him the story was not exactly right.” Influenced by Max Weber, Finley also believed that the important distinctions of early societies were ones of status and that competition in the premodern world revolved around status acquisition and not around gaining capital for reinvestment. Status seeking was negatively correlated with continually productive economic activity because once a person has accumulated enough wealth to reach a higher level of status, they have no incentive for further accumulation. “He also had a perfectly plausible, but I think ultimately not true, theory about slavery,” says Josh. Finley thought of slavery as an impediment to technological development. Higher status individuals associated labor with slaves and were acting as rent seekers who were not interested in reinvesting rents in any kind of productive activity. “When I was young it was exciting to read Finley because he was one of the very few historians of the mid-20th century who was trying to think in terms of models and general theories. He had a theory that was internally consistent and until the thing you are trying to explain turns out to be inconsistent with the model, the model sounded great. When the explanandum changed, the explanation had to change as well.”

Yet Josh Ober’s theory and methodological approach remains quite controversial among historians. “There are those who cling to a kind of positivism and say you should not make any statement that is not there in the evidence itself. So there is no inference. Those folks are bothered by any kind of modeling or use of social theory. They did not like Finley either.” And then there is a second type of pushback to the work that objects to the use of quantification and to the claim that there may be a connection between incentives, market theory and political change. The latter group of people take issue not with the argument underlying the theory, but with the approach itself. Quantification is thought to corrupt the humanistic approach of classical studies, and to be attached to a neoliberal way of thinking.

Yet Josh is overall optimistic. “I think that better methods that advance the field are in the long run going to be accepted. And there is a substantial number of younger scholars who are on board with the idea that there are exciting things to be done in the field of classics.” Much of the excitement comes from the revolution of data digitization that has allowed classicists to use text-as-data and other methods to analyze the past. “One of my students in Classics just finished his master’s in Computer Science and will be working on some very cool text-as-data. Others are using game theoretic approaches to think about civil war and one just finished a big book on the Greek oligarchy. There is a range of topics that we can now actually address by using some of these methods and really make progress.”

The data that is becoming available is by no means perfect, and nobody is more aware of this than Josh and other “quantitative” classicists. A long-standing workshop series on Issues of Data Scarcity in the Ancient Mediterranean organized by graduate students in the Stanford Classics department is meant to be a forum for scholars to discuss these challenges. If data missingness plagues HPE folks, then one can only imagine how central the question is for ancient historians. “We have a great deal of information for some city states like Athens or Sparta, but for others there is basically one line that says it existed. In some cases, we don’t even know where it was.”

Yet there is enough data to allow for a range of inferences, and in some cases the available information is surprisingly rich. City size can be inferred from the presence of stone walls. The dates of introduction of silver and bronze coinage provide evidence on an economy’s monetization. Combined with remnants of monumental buildings like temples and civic structures, this information allows for comparisons of the development of cities over time and across regions. Additionally, new methods of chemical analysis are improving upon existing skeletal evidence on people’s diets. As graves can be dated fairly accurately, and cemeteries are class-stratified, one can essentially track over time changes in the diets of both elite and poorer members of society. Wage data provides another clue on the level of inequality. “At least for Athens, we know what people were paid as daily laborers, or for doing political work, such as being a juror or going to the assembly. Wages in drachmas can be converted to wheat wages to allow for cross-society comparisons. So one can create a baseline of how well the people at the bottom of the society are doing and estimate what was happening with those at the top. Then one can come up with models of inequality and match them against the skeletal evidence.” Combined estimates from these sources indicate that inequality in Athens and other developed parts of the ancient Greek world was relatively low, closer to 1950s United States than to 1900s UK.

Josh’s next book moves away from quantitative analysis, yet does not sever ties with social science. It is a study of the ways in which the Greeks thought systematically about instrumental rationality. “Did the Greeks have a conception of rational choice in more or less the way that contemporary choice theorists think about it? Did they think about preferences, transitivity, coherent beliefs conditioned by assumptions about probability such that a choice among available options is expected to maximize utility? Basically, what I would argue is yes, they did. In fact they thought about this much more seriously than people have realized.”

The normal way to think about Greek rationality in the work of classical philosophers is as rationality of ends. To be judged as rational, one needs to be striving for a goal objectively determined as optimal by each philosopher’s criteria. Yet Josh argues that Greeks also had a conception of rationality based on individual subjective preferences and choices conditioned by the behavior of other agents, a setup very close to game theory. “The Greeks don’t yet have the mathematics behind such theory, but though they are not doing it mathematically they are doing it intuitively.” The evidence for this “is hiding in plain sight” in the ancient texts, properly reinterpreted. If the argument proves convincing it would demonstrate that rational choice is not a way of thinking unique to modernity, but one that was available to people in the past and thus better thought of as a general microfoundation of human behavior. Josh provides me with an example of how one can read a section of the Iliad as an extensive form game – for this alone, I think the book is worth reading.

** For just a glimpse of the kinds of data used by the digital humanities to shed light on the economy and society of the Greek and Roman world, here you can browse cities, ports, transportation networks and Atlases of places mapped to the textual sources that refer to them.