HPE and the Confederate Constitution

I wrote my PhD dissertation, back in the late-1990s, on the Congress of the Confederate States of America. It was a series of three essays, and they were very much HPE — before there was an HPE. The first two used the Confederate Congress as a comparative case to study contemporary questions in the US Congress literature (on party effects and ideological voting, respectively). These essays found there way into the American Journal of Political Science, and they are much better cited today than the third essay — which was actually my favorite to write. It was more of an APDish exploration on why political parties didn’t exist in the Confederacy. That third essay led to an exchange with Richard Bensel in Studies in American Political Development (see here, here, and here).

Upon graduation in 1999, I considered writing a book on Civil War politics. But I had a lot of other ideas (for papers), and I didn’t think I was ready to write a book. Plus, I didn’t want to be known as “Civil War guy.” I told myself I’d eventually get back to it. Now, more than 20 years later, I’m starting to think about it again. The political science world is much more HPE friendly than it was in the 1990s, and I think there are still interesting questions to explore by looking at the Civil War era. And other scholars — like Nathan Kalmoe — have done some really great work in the area recently with broad appeal.

Thus, in this post, I want to explore some of the things I covered in that 1999 SAPD exchange with Bensel. In short, the reason that parties didn’t exist in the Confederacy was because of partisan voting during the Confederate Constitutional Convention. Specifically, the Democrats in the convention used their superior numbers to eliminate the underlying economic issues that had divided them from the Whigs during the Second Party System — in a way that was beneficial to the Democrats.

But before delving into those issues, though, let’s first do a little history.

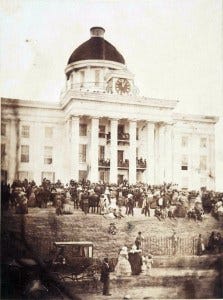

On February 3, 1861, delegates from seven slave states — Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolin, and Texas — convened in Montgomery, AL, to create the Confederate States of America.[1] The number of delegates each state received was equal to its number of U.S. representatives and senators. Thus, the Montgomery Convention was composed of fifty delegates, with Georgia being the largest contingent (ten) and Florida being the smallest (three). Voting was conducted via the unit rule, with each state delegation, regardless of size, possessing one vote. The individual “yeas” and “nays” could be recorded, however, upon the motion of any one member, seconded by one-fifth of the members present, or at the insistence of any one state.

Within five days, the Montgomery Convention adopted a temporary governmental structure and provisional Constitution, based on the U.S. system. With the completion of these immediate tasks, the delegates turned their attention to creating a permanent governmental structure. In doing so, the fifty delegates of the Montgomery Convention became the Provisional Congress, a unicameral body whose primary task was to serve as a national governing authority for a maximum of one year or until a permanent Constitution and governmental structure could be constructed, whichever came first.

On February 9, 1861, a twelve-man committee — evenly divided between Democrats and Whigs — was appointed to draft a permanent Constitution. Three weeks later, the Committee of Twelve completed its work and presented a draft of a Permanent Confederate Constitution to the Provisional Congress. Over the next twelve days, the members of the Provisional Congress split their time between regular and special duty, meeting as a national legislature in the morning and as a Constitutional Convention in the afternoon.

On March 11, after much debate and amending, the Permanent Constitution was unanimously accepted, thereby establishing a permanent Confederate government. The Permanent Constitution — which can be read here — was remarkably similar to the U.S. Constitution. This is unsurprising, as the “Confederate Founders” saw themselves as the true heirs to the original U.S. Founders. One important difference between the two documents, however, was the Confederate Constitution’s open approval of slavery. Whereas the U.S. Constitution hid slavery behind references like “other persons,” the Confederate Constitution referred to “slave” or “slavery” ten times.[2] Perhaps the most telling example is in Article I, Section, 9, Clause 4: “No bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.”

So while Jefferson Davis, the new President of the Confederate States of America, was reputed to have said “We are not fighting for slavery; we are fighting for independence,” a reading of the Confederate Constitution underscores the importance of slavery in the Confederate Founders’ minds.[3]

But while the convention delegates clearly agreed on the importance of preserving slavery rights for all time, they also disagreed on major economic matters. It was during the Constitutional Convention, I argue, that the old partisan divisions of the Second Party System reemerged and the issues underlying the Democrat-Whig conflict were eliminated. Despite initial attempts at bipartisanship, through an equitable partisan division on the Committee of Twelve, the Democrats could not resist using their majority status in the Convention to amend the Constitution to their benefit. As Table 1 indicates, the Democrats held 32 seats to the Whigs’ 17 (with one unknown) — and controlled 5 states to the Whigs’ 2.

What were the major economic issues at stake? The two most important — which had been the basis for Democrat-Whig clashes over the previous quarter century — were (a) protective tariffs and (b) federal funding for internal improvements.[4]

Using the partisan data in Table 1, I was able to make predictions about how members (and states) should have behaved, if partisanship was the guiding force behind their actions. Since the 1830s, Democrats had been opposed to governmental influence in the economy, while Whigs had been in favor of such an approach. If there were motions to prohibit protective tariffs and federal funding for internal improvements during the Confederate Constitutional Convention, Democrats should have supported them while Whigs should have opposed them. Further, unit (state) votes should have broken down along partisan lines, with “prohibition” winning 5 to 2. Individual roll calls, when requested, also should have broken down along partisan lines.

Protective Tariffs

First up was the protective tariff issue, which was broached on March 4. That morning, in a letter to his wife, Thomas R. R. Cobb of Georgia noted the general feeling in the chamber: “The tariff question is troubling us a good deal. The absolute free trade principal is very strongly advocated.” The delegates were in the midst of discussing the first article of the Permanent Confederate Constitution, when they turned their attention to the first clause of the eighth section, which read:

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, for revenue necessary to pay the debts and carry on the Government of the Confederate States; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the Confederate States.

Seizing the moment, the advocates of free trade made their move. Robert Barnwell Rhett, a Democrat from South Carolina and a strong proponent of states’ rights and free trade, moved to amend the clause by inserting after the words “Government of the Confederate States” the following phrase:

no bounties shall be granted from the Treasury; nor shall any duties or taxes on importations from foreign nations be laid to foster or promote any branch of industry . . . .

The Whigs first tried to table Rhett’s amendment and then amend it (and thereby make it toothless) — but were defeated in each attempt. Finally, Rhett demanded the question on his motion to amend, which was seconded, and a vote was taken by state.

Results from the vote on Rhett’s amendment, as well as partisan vote predictions, appear in Table 2.

The vote broke down perfectly along partisan lines. Democrat-controlled states are predicted to vote for Rhett’s antiprotectionist amendment, and all five of these states – Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas – voted yea. Whig-controlled states are predicted to vote against Rhett’s antiprotectionist amendment, and both of these states – Georgia and Louisiana – voted nay. The final state-vote, then, was 5 to 2 in favor of Rhett’s amendment. Consequently, the first clause of the eighth section of Article I, as amended, read as follows:

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, for revenue necessary to pay the debts and carry on the Government of the Confederate States; but no bounties shall be granted from the Treasury; nor shall any duties or taxes on importations from foreign nations be laid to foster or promote any branch of industry; and all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the Confederate States.

Thus, behind strongly partisan voting, the Democratic majority was able to amend the Constitution to prohibit the creation of protective tariffs. Thus, with this amendment, as Charles Robert Lee, Jr. states, “the issue of the protective tariff was laid to rest, as far as the Confederacy was concerned.”

Federal Funding for Internal Improvements

Fresh from their victory on protectionism, the Democrats sought to rid themselves of the internal improvements issue, the second major tenet of the Whigs’ political-economic platform. The general feeling within the Democratic coalition on internal improvements was summarized nicely by Alexander H. Stephens, a Whig from Georgia: “The true principle is to subject the commerce of every locality to whatever burdens may be necessary to facilitate it. If Charleston harbor needs improvement, let the commerce of Charleston bear the burden.”

The internal improvements issue came to a head on March 9, when the third clause of the eighth section of Article I was discussed. This clause read as follows:

Congress shall have the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.

It was here where the Democrats made their move, as Robert Barnwell Rhett once again led charge, offering the following amendment to be tacked on to the end of the third clause:

but neither this, nor any other clauses contained in this Constitution, shall ever be construed to delegate the power of Congress to appropriate money for any internal improvement intended to facilitate commerce.

In response, Francis R. Bartow, a Whig from Georgia, moved to lay Rhett’s amendment on the table and demanded the question, which was seconded, and a vote was taken by state. Voting results on the motion to table, as well as partisan vote predictions, appear in Table 3. To reiterate, a partisan model of vote choice would predict that Democrat-controlled states should oppose federal funding of internal improvements (and thereby oppose the tabling of Rhett’s amendment), while Whig-controlled states should favor federal funding of internal improvements (and thereby favor the tabling of Rhett’s amendment).

The vote broke down reasonably well along partisan lines: the Democrat-controlled states of Florida, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas voted nay, thereby opposing tabling, while the Whig-controlled state of Georgia voted yea, thereby supporting tabling. There were, however, two partisan prediction “errors,” as Alabama voted yea, while Louisiana was divided and did not cast a vote. Thus, the motion to table was defeated by a vote of 4 to 2, as the Whigs were unable to stymie the Constitutional engineering of the Democratic majority.

In addition to these state-level voting results, the individual-level voting results were recorded (at the instance of South Carolina) on Bartow’s tabling motion. Forty of the fifty delegates voted, and of the forty individual votes cast, I can make partisan predictions for thirty-nine of them. Of those thirty-nine votes, party predicts thirty-one (79.5 percent) correctly. Further, the voting errors were distributed evenly across the two parties, as nineteen of the twenty-three Democrats (82.6 percent) and twelve of the sixteen Whigs (75 percent) voted in the predicted direction. Thus, two results follow from these individual totals: Democrats received their preferred outcome, thanks to partisan voting and their majority status, and the Democrat-Whig divisions that existed prior to secession were still quite visible at this time on the internal improvements issue.[5]

An additional amendment was tacked on to the end of Rhett’s original amendment, allowing Congress to make certain appropriations, but only in the case of aiding navigation or improving harbors. Moreover, duties would be laid on the vessels that benefitted from those improvements, to pay the costs to maintain them. The full text of this amendment is as follows:

except for the purpose of furnishing lights, beacons, buoys, and other aids to navigation upon the coasts, and the improvement of harbors and the removing of obstructions in river navigation, in all which cases, such duties shall be laid on the navigation facilitated thereby, as to pay the costs and expenses thereof.

With the addition of this amendment, Rhett’s original amendment was passed, laying the issue of internal improvements to rest along side that of the protective tariff.

Thus, the Democratic majority in the Provisional Confederate Congress was able to eliminate constitutionally the two major issues underlying the Whig party’s existence.

Conclusion

Students of political history have concluded that the Confederacy was devoid of a party system during its short existence as an independent nation. Yet, the traditional Democrat-Whig divisions, which had been in place in the South since the 1830s, had persisted through the 1850s (after the fall of the national Whig party) and into the state secession convention in 1860–1861. It was at that point that the Democrats used their majority advantage in the Confederate Constitutional Convention to amend the Confederate Constitution to prohibit the two major issues that formed the basis of the Whig party: protective tariffs and federal funding of internal improvements.

When these two issues were prohibited constitutionally, the necessary condition for a Democrat-Whig two-party system was eliminated as well. The Whig Party had organized itself in the 1830s to oppose the Democrats on the major issue of the day: government’s proper role in the economic expansion of the nation. This was the “great principle” that defined the Democrat-Whig party system and, at its heart, lied two issues: protective tariffs and federal funding of internal improvements. These two issues fostered the ideological divide between the two parties up to the South’s secession. When these two issues were eliminated through constitutional amending, however, the “great principle” was eliminated as well, resulting in the destruction of Democrat- Whig divisions and the emergence of a “no party” system in the Confederacy. In order for a new partisan system to have developed, a new “great principle” had to have emerged – something that did not happen during the Confederacy’s short existence.

This is illustrated in a W-NOMINATE scaling of House roll-call votes from the Second Confederate Congress — which met from May 2, 1864, to March 18, 1865 — below. Former-party tokens are used for members’ ideal points.

Other than a few former-Whigs anchoring the left part of the space, the former partisans are dispersed widely. And there appears to be little ideological structure. The new issues created by war – like conscription, habeas corpus, and impressment – did not fit cleanly into the former partisan politics, and a “new” party system, organized around the new issues in play, did not emerge before the war had ended.

Would a new party system have emerged, had the war been prolonged? Historian Richard Beringer suggests that the answer might be “yes,” as a roll-call analysis finds that “peace” and “war” factions had grown more stable in the Confederate Congress as the war had progressed.

What if the Confederacy had won the war? According to Beringer: “In a victorious Confederacy new political parties doubtless would have resumed rivalry along old Whig-Democratic lines.” This, of course, is merely speculation. But in a victorious Confederacy, one thing is for certain: that new (old) party system would have necessarily been based on issues other than protective tariffs and federal funding for internal improvements.

[1] Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia would secede and join the Confederacy later.

[2] It also references “negro” three times and “African” once.

[3] This truth is embedded in the famous “cornerstone” speech made by Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephen, when he said, on March 21, 1861, that the Confederate government’s “foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.”

[4] A third issue — a central bank — was discussed throughout the life of the Confederacy, but a Bank of the Confederate States of America was never established. See Richard Cecil Todd, Confederate Finance, 19–20.

[5] Do these significant party results hold up, if we include former-party affiliation along with W-NOMINATE scores based on members’ votes from the Provisional Confederate Congress (259 roll calls in all) in a multivariate analysis? The answer is “yes” — see the logit results in Table A1 below.