Identity Politics: Economic Incentives, Elite Capture, and Collective Memory

by Michele Rosenberg

Identity politics plays a central role in contemporary political divisions—shaping voting behavior, social preferences, and conflict. Notably, these patterns often contradict material self-interest. For instance, poor white voters in the U.S. often oppose redistribution—despite being its likely beneficiaries (Alesina and Glaeser, 2004). This raises two fundamental questions: What role do economic incentives play in shaping identity politics and racial hate? And, if not economics, what forces drive these behaviors?

Slaveocracy: Elite Capture and the Support for Slavery

To address these questions, we study slavery—arguably the most foundational exclusionary institution in U.S. history and one that continues to shape political identity today (Acharya et al., 2016). While economic historians have thoroughly documented the material incentives that made slavery profitable for slaveowners (Fogel, 1989; Wright, 2006; Olmstead and Rhode, 2010), a major puzzle remains: why did the broader white population—most of whom did not own slaves—so staunchly support the institution? Before the Civil War (1861–1865), 75% of Southern white men were non-slaveholders, yet they defended a system that undermined regional development, depressed investment in human capital, slowed technological progress, and concentrated wealth in the hands of a small elite (Sokoloff and Engerman, 2000; Nunn, 2008; Wright, 2022; Hornbeck and Logan, 2023). More generally, why do extractive institutions that benefit only a narrow elite persist, even under democratic rule?

In new research with Federico Masera, we study how elite economic incentives shaped broader political behavior. We focus on slavery’s profitability—driven largely by cotton—and model how changes in agricultural comparative advantage during Westward Expansion altered elite interests. As the population moved westward, the colonization of new land shifted counties’ comparative advantages in the use of slave labor. Figure 1 shows the geographic variation of changes in comparative advantage between 1810 and 1860 along with the Westward Expansion. Exploiting this variation, we estimate how changes in the returns from slavery translated into political support in Congress. We find a large effect of slave profitability on support for the institution. Interestingly, the effects are too large to be explained by changes in elite voting behavior alone. On the contrary, only about 30% of the change in pro-slavery votes can be attributed to slaveholders. This suggests that economic motives extended beyond the planter class and motivates our analysis of the mechanisms that allowed the planter elite to secure the support of the broader white population.

Elite Capture at Work

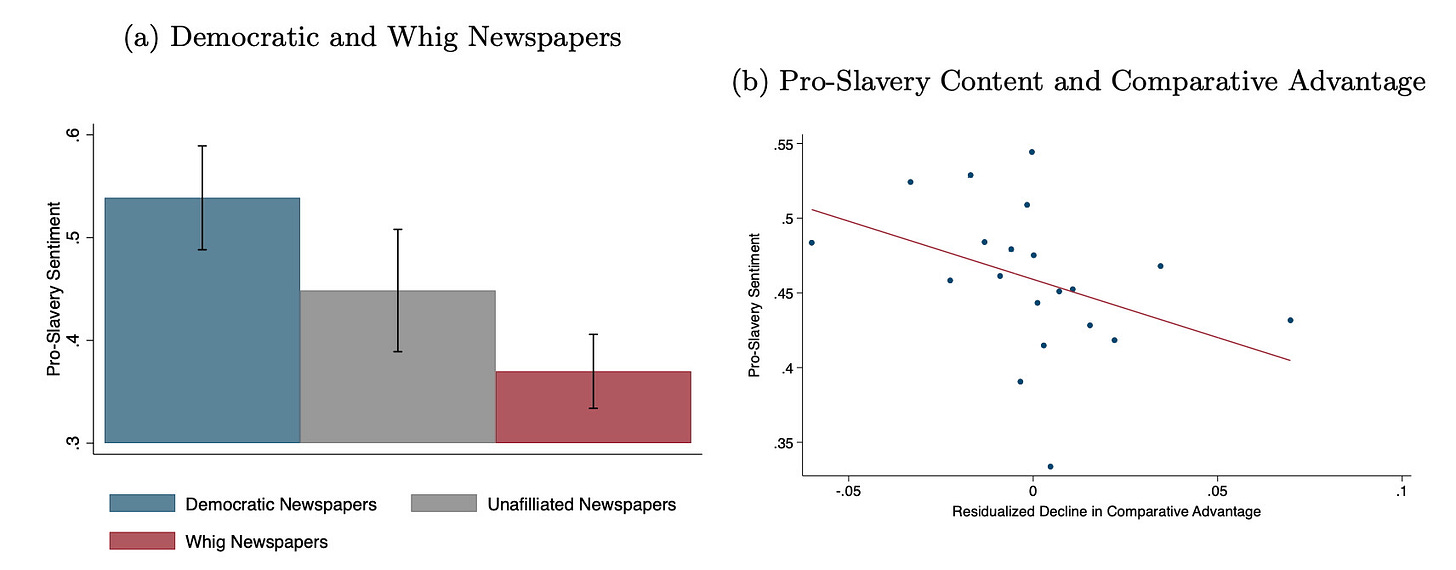

We find evidence that planter presence was critical in shaping political behavior. Using a sample of linked individuals between 1850 and 1860, we show that only the planter elite migrated out of counties where the return from slavery was declining—relocating to areas with higher returns (Figure 2). In addition, wages for white laborers were higher in plantation counties, and newspaper content was biased in favor of slavery. As the returns from slavery fell, both wages for white laborers and newspaper content declined (Figure 3).

These results indicate that planters created clientelistic relationships—offering wage premia and security in exchange for loyalty, and threatening retaliation when support was withdrawn. Their control of local media further allowed them to shape political preferences. However, when planters migrated westward—following changes in comparative advantage—support for slavery among non-slaveholders declined. Our analysis indicates that the planter elite captured the political system through their weight in the local economy. As the profitability of slavery declined, planters relocated to more productive land, severing patron-client relationships with local white laborers, decreasing their investments in political persuasion through pro-slavery content in newspapers, and creating new opportunities for non-slaveholders to acquire land and attain economic independence. Because access to wealth required land acquisition—a path blocked by the planters’ monopolization of the most valuable agricultural land (Wright, 1978)—this pattern diminished the income available to white laborers tied to the slave economy while simultaneously opening new opportunities outside of it, ultimately eroding support for slavery. The results align with historical evidence indicating that political consensus in the slave economies was the result of a mix of coercion and incentives (Genovese, 1975; Genovese, 1988; Bolton, 1994; Merritt, 2017). More broadly, the paper shows how even under democratic regimes, the concentration of economic power allows elites to influence the political process and sustain institutions that are morally repugnant, economically inefficient, and serving only their own interests.

The Civil War and Racial Hate in the U.S. South

Results in Masera and Rosenberg (2024) indicate that support for slavery was rooted in economic incentives. When material conditions were removed, political behavior shifted rapidly. This conclusion, however, raises the question of why racial animosity persisted long after emancipation. From an economic perspective, because discrimination is inefficient, it should vanish in competitive markets (Becker, 1957). Yet, while emancipation removed the material foundation of slavery, segregation, violence, and hate endured.

To explain the geography and persistence of racial hate in the postbellum period, Walker, Rosenberg, and Masera (2025) investigate the role of the Civil War in the formation and transmission of a social identity that sustained segregation and racial hate in the Southern United States throughout the twentieth century. We show that the war experience played a critical role in shaping collective identity in the South. While the war led to the emancipation of the Black American population, it also generated a narrative of loss and resentment that became central to white Southern identity, tied to opposition to emancipation and the memory of the Confederacy. We construct a measure of local battle exposure and show that communities more affected by the war exhibited stronger post-war support for segregationist candidates, committed more lynchings, and engaged in more white supremacist activity. Figure 4 shows the main result.

The Formation of Social Identity

To understand the war’s effect, we compare towns with similar overall battle exposure but whose soldiers fought in battles with different characteristics. Exposure to the largest and most renowned battles produced effects nearly three times greater than less prominent but equally deadly engagements. Battles involving Black troops had effects eight times larger than those fought only by white soldiers. These findings highlight two channels: the symbolic power of shared experiences and the identification of Black soldiers as the enemy. We then turn to remembrance, a crucial step in forging collective identity (Anderson, 2006; Zubrzycki and Wózny, 2020). Cemeteries where communities honored fallen soldiers, organizations such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy (Cox, 2019), and white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan (Davis, 2023) played key roles in fostering an environment that sustained racially discriminatory social norms.

We then ask whether collective memory was shaped primarily by elites or grassroots actors (Halbwachs, 2020; Wagoner, 2020). Examining the initiators of Confederate memorials, we find that the families of Confederate soldiers—rather than wealthy individuals or local institutions—were primarily responsible for erecting monuments in communities with higher battle exposure. These results suggest that collective memory was institutionalized from the bottom up. Confederate families led efforts to memorialize the war, building monuments, shaping school curricula, and transmitting identity within households. Crucially, this process was not driven by planter elites. Our evidence shows that the effect of battle exposure does not depend on the size of the formerly enslaved population or the presence of large planters—factors that were key determinants of pro-slavery sentiment in the antebellum South (Masera and Rosenberg, 2024).

Mechanisms of Transmission and Today’s Legacy

Last, we contrast two mechanisms of transmission: one in which Confederate culture persisted through geographically rooted elements, such as landmarks and local institutions reinforcing collective memory, and another in which it was sustained through the intergenerational transmission of individual preferences within families. Comparing a measure of battle exposure that captures family-level exposure to the war to our baseline measure, we find that both channels played an important role, with statistically equivalent effects. Today, the war’s effects persist in hate crimes, police violence, and white supremacist rallies, indicating that the war’s memory still shapes racial animus and collective identity.

Conclusions

These two articles together demonstrate the complex relationship between economic structure and political preferences. Masera and Rosenberg (2024) show that the profitability of slavery, embedded in a democratic system, created strong incentives for elites to build broad support for the institution through clientelistic relationships based on their economic weight and control of local media. When planters migrated, these ties were severed, opening opportunities outside the slave economy for poor whites, who subsequently reduced their support for slavery. This suggests that, absent material incentives, racial animosity might have withered away. Instead, the Civil War transformed racial hostility into a durable identity. This new identity emerged from collective mourning, institutionalized by families of fallen soldiers through associations and memorials, transmitted within households, and grounded locally through organizations and physical markers. These monuments celebrated a mythical past, redeeming the dead by inscribing their sacrifice in a symbolic network (Zizek, 2009). Surprisingly, this process of memorialization was largely bottom-up and yet, somewhat paradoxically, elites continued to benefit—leveraging violence and hostility to maintain control over the emancipated Black population. While racial identities were rooted in the economic structures of slavery, the war reshaped their geography, crystallizing animosity into a lasting identity that extended beyond traditional slaveholding regions.

Michele Rosenberg is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Essex. His research spans economic history, political economy, and development. His work investigates the forces that promote or hinder economic progress and political emancipation, focusing on conflict, collective action, and social norms. Michele was previously a postdoctoral research fellow at Northwestern University and at the Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse (IAST).

You have done a good job using historical context to explain why people are voting against their own self interest and letting elites benefit.

I'm sorry that this is a zero-value-added comment, but I just wanted to say that this is a fantastic post and is exactly why I read Broadstreet, even though I am a philosopher and not a historian, economist, or political scientist. If we're going to have a national fight about the profitability of slavery, we should be able to discuss it in nuanced and factual terms, and you are contributing hugely to that.