Industry and identity: How labor migration reshaped culture in 19th century Britain

In the 19th century, European states experienced profound transformations. Agrarian, rural communities gave way to industrial, urban and interconnected societies. Local allegiances were gradually displaced by national identities, as people came to see themselves as part of "imagined communities" far larger than their villages or kin networks.

Labor migration to industrial centers was a central force behind changing identities. Classic theorists of modernization and nationalism—Ernest Gellner, Karl Deutsch, and Eric Hobsbawm—highlighted the role of states and schools in shaping mobile workers into national citizens through standardized, homogeneous cultures. But identity transformation also unfolded from below. As people “exchanged the sluggish, dull life of the rural districts for the bustle of the great cities” (Engels, 1845) and were “rescued from the idiocy of rural life,” (Marx and Engels, 1847) they encountered fellow migrants who spoke different dialects and came from varied backgrounds. Communication across these divides required common linguistic and cultural ground. Eugen Weber, in Peasants into Frenchmen, captures this bottom-up process: “Increased mobility and social exchanges played their part in the spread of national language, as they had in the spread of national currency and measures. Industrialization also helped speed the process. In Vosges, for example, the installation of a cotton industry in the 1870s and its expansion after the 1880s all but wiped out the local dialect when country people moved into small industrial centers.”

But how, exactly, did this process unfold? Weber’s account suggests that industrial centers tended to see their local cultures erased. Many scholars have assumed that local identities persisted mainly in the agricultural hinterlands left untouched by industrialization. Yet this claim remains largely untested and theoretically underdeveloped. Industrial growth doesn’t just attract outside labor; it also creates local employment, reducing incentives for native populations to leave. Even when migrants arrive, whether they come from nearby culturally similar areas or more distant, diverse regions depends on the full landscape of migration opportunities. Industrialization in one location may not draw distant migrants if other regions are simultaneously industrializing and competing for labor.

Another unresolved question in the literature is which identities migrants in diverse settings actually adopt. Education, conscription, and other state-led nation-building efforts often impose the language and culture of the political center—a process well-documented across cases, with France serving as the canonical example. Eugen Weber’s account, and more recent empirical work, illustrate how top-down integration can reshape identities (though this is not the only, or even the most effective means of homogenization). But not all European states pursued such centralized assimilationist strategies. In their absence, identity formation begins to resemble a coordination game. As David Laitin has argued in his work on language, identities that are already widely shared become more valuable for communication—and therefore more attractive. Yet coordination games admit multiple equilibria, making it difficult to predict which cultural norms or identities will prevail when heterogeneous groups converge in migration destinations.

In a working paper with Theo Serlin, we develop a theoretical framework to examine how labor migration shapes identity change. Our focus is 19th-century Britain—a case that, while not devoid of nation-building efforts, lacked the centralized identity engineering characteristic of France. Military service was voluntary, and education remained locally administered. We concentrate on the period of the Second Industrial Revolution, when industrial activity not only surged in scale but also changed in geographic scope. New industrial centers emerged beyond the traditional textile-producing regions, including the coalfields of South Wales and Northumberland, as well as the broader region around London, where industry increasingly clustered to capitalize on growing investment from the City. During the same period, people increasingly migrated over longer distances (see Figure 1).

We examine how industrialization reshaped identity by considering individuals’ incentives to choose both where to live and which identities to adopt. We embed these choices in a theoretical model that connects these migration and identity choices to shifts in the spatial distribution of economic activity—and broader processes of modernization, such as declining migration costs. The advantage of this approach to a more standard empirical design that would link local industrialization to local identity outcomes is that it captures general equilibrium effects: what happens in one location depends on conditions and choices across the entire country. This allows us to study the global impact of local changes.

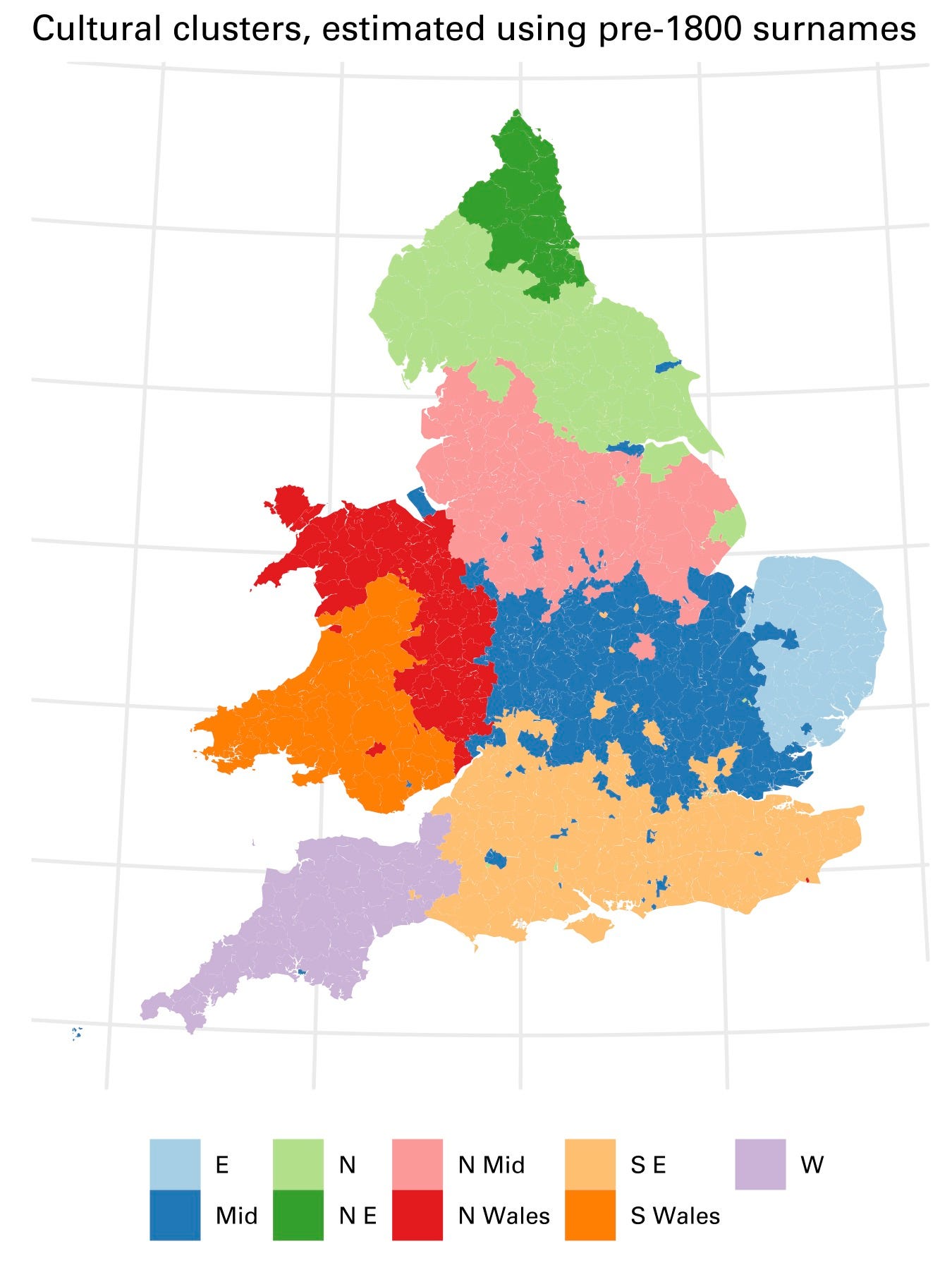

To estimate the parameters of our model, we use rich individual-level data from the 1851 and 1911 censuses, focusing on migration patterns and identity choices—proxied by personal names. We begin by developing a measure for how strongly names reflect regional identities, in two steps. First, we use a data-driven clustering algorithm on surnames in the 1851 census. Without any geographic input, the algorithm recovers spatially distinct groupings across England and Wales—corresponding to recognizable regions like East Anglia, the West Country, and North and South Wales (see Figure 2). These “cultural clusters” are not only spatially coherent; they also predict meaningful behaviors. Migration and intermarriage are more frequent between districts within the same cluster, even when controlling for geographic distance. Next, we construct an empirical measure of how distinctive first names are to each cultural cluster. We validate this measure in multiple ways, showing that names consistently predict behaviors tied to identity, including spoken language, marriage choices, and migration patterns.

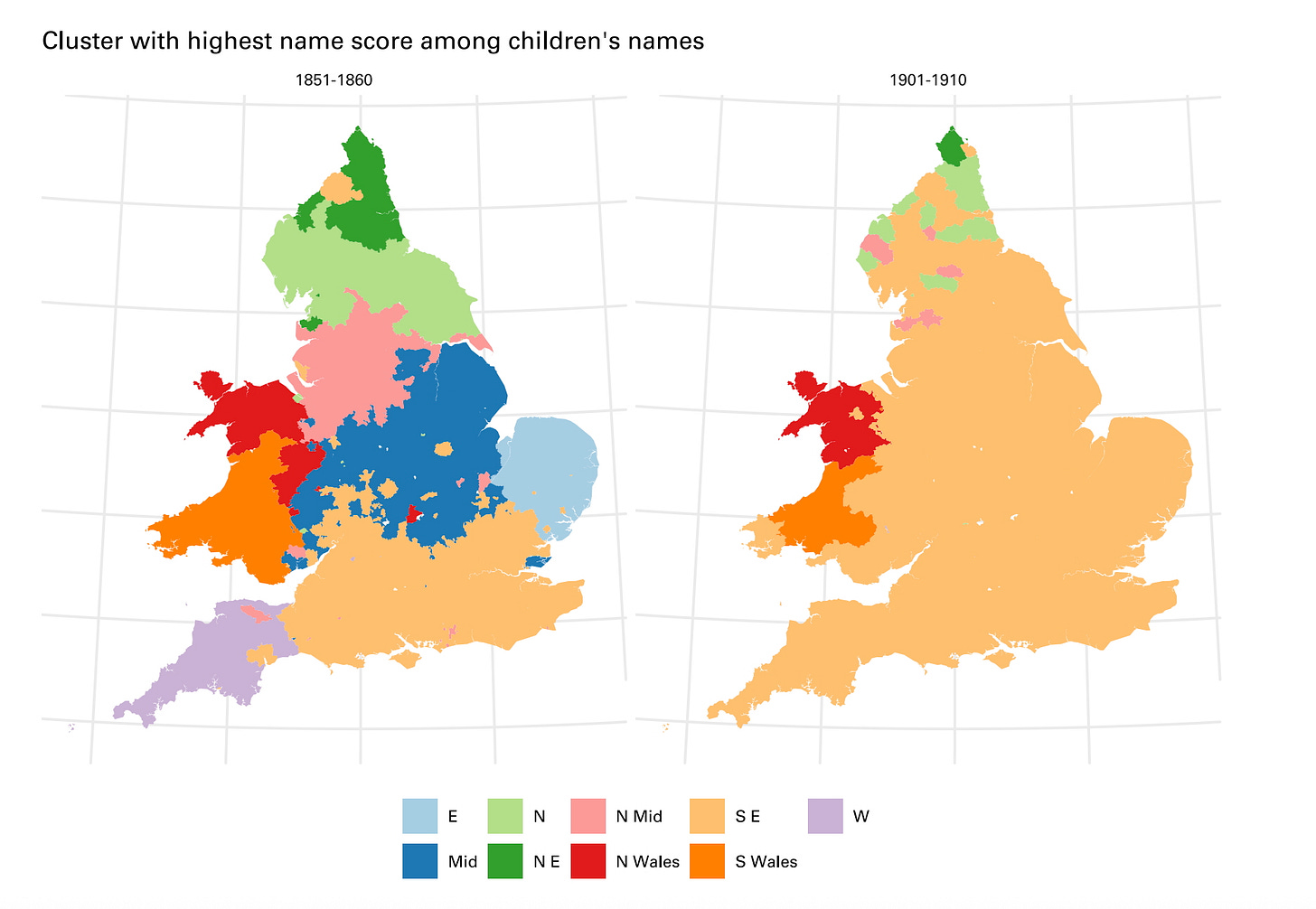

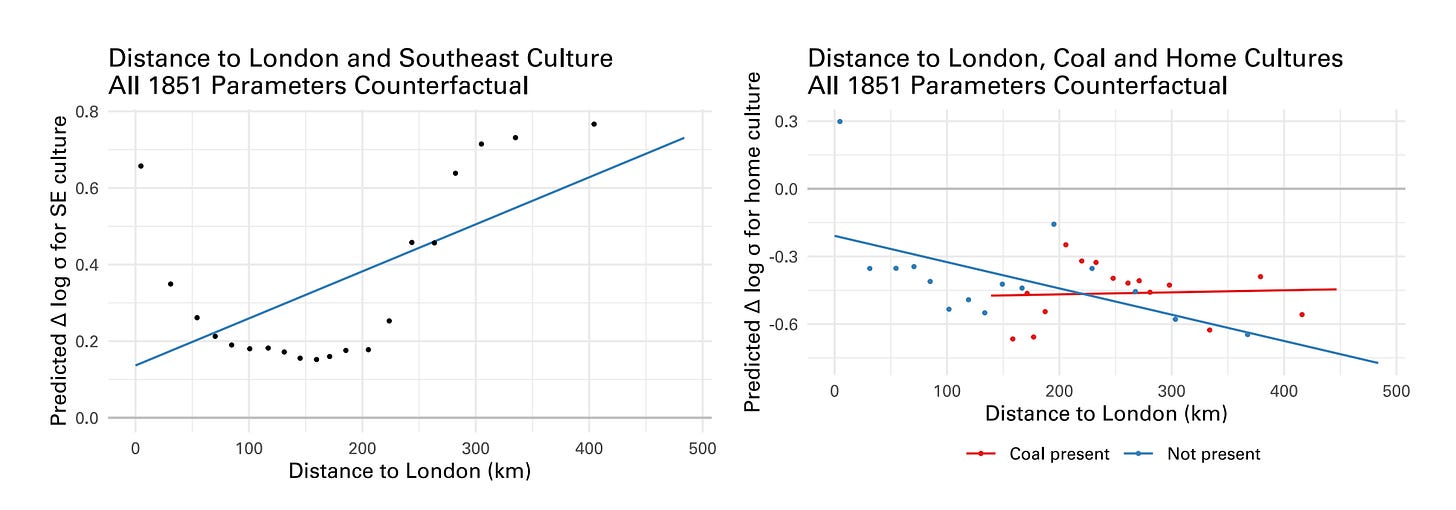

Using names as a proxy for identity, we document key patterns of cultural change between 1851 and 1911. We find convergence toward naming practices associated with the Southeast (SE) cultural cluster—the area surrounding London (see Figure 3). Entire cultural clusters disappear from the map. This convergence is especially pronounced in peripheral regions, as measured by distance from London (Figure 4, left). However, industrial development—proxied by the presence of coal—moderates this effect. Peripheral areas gravitated toward the identity of the Southeast only when they lacked industrial growth. Where industrialization did occur, local cultural identities proved more resilient. Industry did lead to cultural change, but only in the center of the country (Figure 4, right).

Our theoretical model explains these observed patterns (see Figure 5). To better understand the mechanisms linking economic development, migration, and cultural change, we conduct counterfactual simulations—effectively asking what cultural outcomes would have looked like had industrial activity remained at its 1851 levels. These exercises show that industrialization fully accounts for the rise of Southeast identity markers. This is because much of the period’s economic growth occurred near London. Because SE culture was already widespread, migration toward this region amplified its popularity due to coordination dynamics. Economic development favors broader adoption of identities shared by many.

Our counterfactuals also reveal that industrialization's effect on local cultural loss is location-dependent. In central regions, high rates of in- and out-migration facilitate cultural turnover. In contrast, industrialization in peripheral areas attracts fewer migrants and retains more of the local population—thereby helping to preserve regional identities. This worked to counteract broader developments during this period. Our model shows that falling migration costs—a distinct component of modernization—exerted broad pressure on the periphery to adopt the SE culture. Where industrialization occurred locally, however, it acted as a counterforce—slowing or even stalling peripheral cultural convergence.

Our framework and findings help illuminate why some industrializing peripheries retained distinctive cultural identities. One such case, described in work by Elliott Green, is the Basque Country, where the development of ore production and steel manufacturing drew migrants from the surrounding region into Bilbao—diverting movement away from Madrid and reinforcing local cultural cohesion. Similar dynamics played out in Catalonia and Scotland.

More broadly, our study clarifies how bottom-up forces shape the cultural map, even in the absence of strong state-led nation-building. While our model abstracts from widely studied mechanisms like education, it still explains a substantial share of the identity shifts observed in 19th-century Britain. The interplay between uneven economic development and growing mobility remains central in today's world—particularly across the Global South. A framework like ours offers a foundation for understanding how cultural identities evolve in response.

Fascinating paper! It's particularly interesting to see a non-state capacity justification for the persistence of distinct Basque and Catalonian identities in Spain vs. Occitanian identities in France.

I found this interesting and suggestive. It is a shame there isn't a comparison with the pre-industrial cultural provinces identified by Phythian-Adams (as Day did in their paper) or more engagement with P-A's model of how cultural provinces were formed in Britain.