Intellectual Life in Early Modern Europe

by Valentin Figueroa

Creative workers tend to co-locate geographically: computer science researchers cluster in Silicon Valley, literary writers in New York, and country musicians in Nashville. Agglomeration facilitates knowledge spillovers, enables faster and better matching between firms and workers, and generates economies of scale in the provision of shared inputs such as computing clusters, publishers, and recording studios. Through these agglomeration economies, the spatial concentration of creative workers enhances productivity and innovation.

Despite their central role in modern urban economics, we know relatively little about agglomeration economies in historical contexts, particularly before the 18th century. It is evident that the arts and sciences experienced periods of efflorescence in renowned cities, such as Florence during the Renaissance. However, systematic data from these earlier periods remain scarce.

In an ongoing research agenda, in collaboration with Gary Cox, we begin to address this gap by assembling the largest panel database of published authors from the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment (c. 1500–1800). Drawing on large bibliometric databases and national biographical dictionaries, we study thousands of book authors. Our panel tracks authors throughout their entire careers, recording—for each year of their lives—the cities in which they lived, their collaborators, the learned societies and educational institutions they joined, and the books they published.

Agglomeration and Creativity in the British Isles

Our first study, which appeared in Explorations in Economic History this year, focuses on London’s knowledge economy. We examine early modern London because it featured all three main sources of agglomeration economies: knowledge spillovers, matching potential collaborators, and sharing indivisible inputs.

London was an epicenter of creative work. For anyone hoping to meet European scholars visiting Britain, the chances were better in London than anywhere else. The city also boasted a plethora of social clubs, cafés, and learned societies where scholars and intellectuals gathered to exchange ideas. These venues (and the relatively weak regulatory power of metropolitan guilds) made it easier to find interlocutors and collaborators. For example, the engineer John Smeaton began attending meetings at the Royal Society immediately after moving to London.

Productive interactions were not limited to those within one’s own field. According to a recent book, for example, William Shakespeare’s neighbors in the parish of St. Helen’s, London, may have influenced his plays. One such neighbor, Edward Jorden, was among the first English doctors to specialize in female health and was called as an expert witness in high-profile witch trials. A historian has conjectured, based on contextual evidence and the content of Shakespeare’s and Jorden’s writings, that their relationship might have shaped the portrayal of the “three witches” and the psychological depth of Lady Macbeth in Macbeth.

In addition to knowledge spillovers and advantages in matching with potential collaborators, London also offered cutting-edge public goods valuable to writers and researchers. For example, the city was home to England’s first professorship in mathematics (the Gresham Chair in Geometry, established in 1596), its first learned society (the Royal Society, founded in 1660), and its first astronomical observatory (the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, established in 1675). Moreover, authors could sell their works through London’s many bookstores, and playwrights could stage their plays in London’s many theaters.

To quantitatively assess whether residing in London benefited authors, we drew on our panel database of British authors from the 1470s to 1800. In this phase of our research, we focused exclusively on prolific authors—those who published at least five works listed in the English Short Title Catalogue. For these individuals, we reconstructed full residential histories using biographies from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. For illustrative purposes, Table 1 presents the top five authors by field, ranked by the availability of their works in modern library holdings.

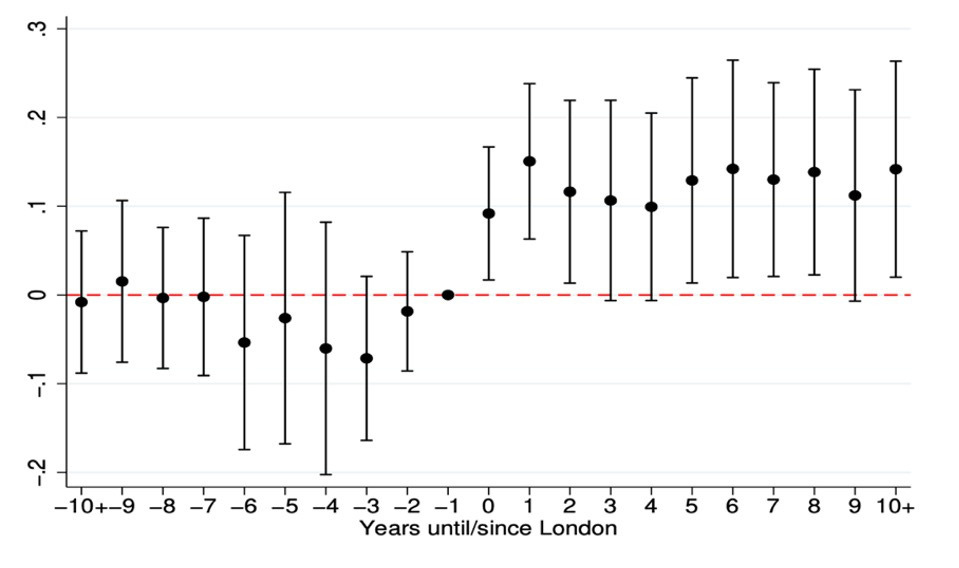

We follow the standard econometric approach in urban economics and regress an author’s productivity on residence in London, controlling for year and author fixed effects. Intuitively, we measure how much more (or less) productive authors became upon moving to (or from) London, compared to other authors who didn’t move that year. The event-study plot in Figure 1 shows that authors were typically not becoming more productive before moving to London. Once they moved there, however, they experienced a sharp and persistent productivity boost that lasted for at least ten years.

The “London premium” we estimate represents a 37% boost relative to the average annual productivity in our sample. Our estimate of the London premium persists when we control in our regressions for age and age-squared, time-varying wealth shocks, and when we exclude authors from the sample after they presumably retired or before they graduated from university. Interestingly, London’s premium did not always exist¾it emerged in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Why did living in London confer such a premium? We provide evidence that authors residing in London benefited from knowledge spillovers and enhanced collaboration opportunities. As shown in the event-study analyses in Figure 2, authors who moved to London became more likely to form close intellectual collaborations (left plot), particularly in the first few years after their move, and to join the Royal Society (right plot).

London also afforded advantages for publishing books, once they were written, because the London’s Stationers Company had monopoly rights over printing between 1577 and 1711. Yet non-London authors in our sample published two-thirds of their books in London, and the city’s premium persisted after 1711.

A Cross-Regional Analysis of Agglomeration Economies

Another part of our project adopts a cross-regional approach. Using harmonized data from different regions, we examine changes in the knowledge economies of Britain and the Netherlands (in the northwest) and Spain and Italy (in the south) from 1500 to 1700. The data we have explored so far suggests that urban knowledge economies in the south began to diverge from those in the northwest in the seventeenth century. In the south: (i) intellectual interactions became less predictive of published output; (ii) clustering of authors in creative cities diminished; and (iii) urban productivity premiums—authors' boost in output when they moved to leading cities—declined.

These changes suggest a significant transformation in intellectual labor markets that has not yet been explored in the historical literature on the “Little Divergence” (the take-off of living standards in the European northwest relative to the south before the Industrial Revolution). We believe the divergence we observe may have political origins, largely stemming from transformations that began with the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. In Protestant regions, ecclesiastical confiscations triggered a process of human capital reallocation, flooding the secular labor market with educated individuals (see, e.g., here and here) who had greater flexibility in choosing where to work than centrally appointed clerics. In contrast, in Catholic regions, the repressive response to the Reformation created significant barriers to the intellectual interactions that are central to agglomeration economies.

The Spanish Inquisition and Intellectual Isolation

We have explored political barriers to intellectual activity in a third project, which examines the consequences of the Spanish Inquisition’s enforcement of Catholic orthodoxy.

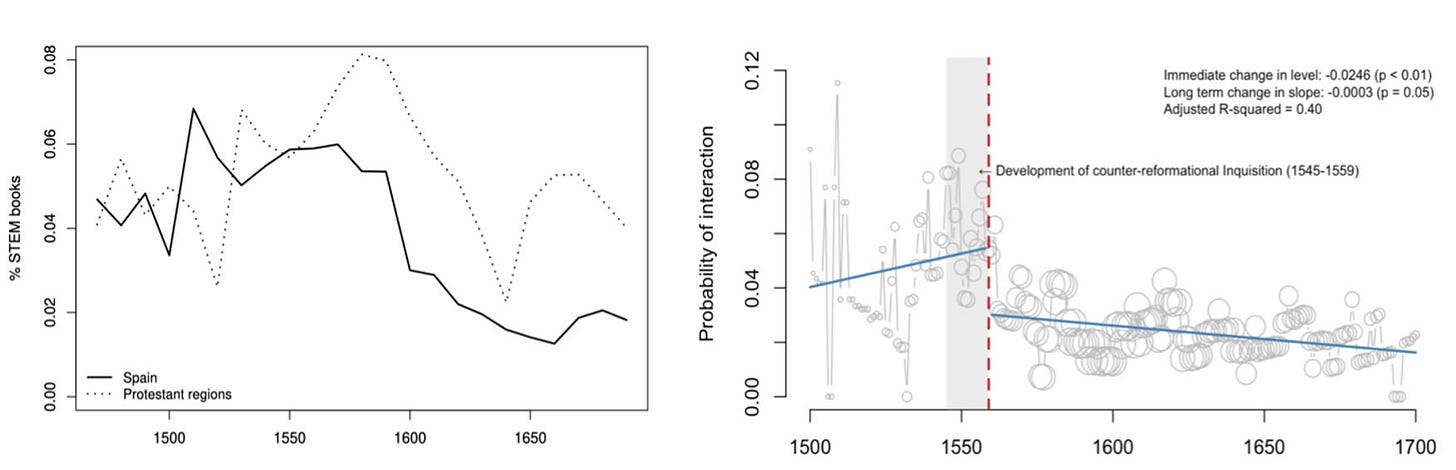

Founded in 1478 and initially focused on persecuting suspected Jews, the Spanish Inquisition shifted its efforts toward Protestantism after the onset of the European Reformations, and particularly during the Council of Trent (1545–1563). The discovery of Protestant networks in two Spanish cities in 1557-58 prompted a dramatic and highly publicized increase in inquisitorial activity. Authorities responded to this shocking discovery by banning travel to foreign universities, publishing an index of forbidden books, and declaring that possession or reading of these books would be punishable by death. Additionally, fourteen people were burned at the stake in Valladolid during a massive auto de fe designed to awe; persecution of foreigners suspected of being Protestant sharply increased; the highest Catholic authority in the Spanish Empire, the Archbishop of Toledo, was arrested in part for his interactions with suspected Lutherans; and inquisitorial activity reached peak levels.

Given that the contours of heresy were blurry and continuously redefined, and that even interaction with suspected heretics was policed by the inquisitors, we argue that scholars should have reacted to inquisitorial changes by limiting their contacts and by exiting certain fields and institutions. This should have hurt STEM output the most because interacting with others working on similar problems is essential to progress in the sciences.

Figure 3 summarizes our main findings. The left panel shows that the share of STEM book publications in Spain declined after the 1560s relative to Protestant Europe. The right panel shows the proportion of Spanish authors whose biographies mentioned an instance of intellectual interaction each year. After the transformation of inquisitorial persecution in 1558-9, we detect a statistically significant reversal in the previously upward trend in interactions; and a pronounced immediate drop in the propensity to interact with other intellectuals. We also detect a migration of authors out of universities (secular educational institutions) into convents and religious colleges.

Our findings contradict a revisionist understanding of the Spanish Inquisition (e.g., this), which argues that its targeting and punishment of scientists has been grossly exaggerated; that it lacked the capacity to enforce book bans; and that it likely had little effect, given that Spain’s Golden Age (1492-1657) began after the Inquisition was founded (1478) and co-existed with it for over 150 years. Instead, we argue that the Inquisition’s direct targeting of specific scholars, theories, and books was less important than the chilling effects that such efforts produced: inducing scholars to reduce their interactions with anyone the Inquisition might scrutinize; and prompting various forms of self-censorship.

Too Long, Didn’t Read?

Creative workers benefit from free labor markets that allow for mobility across locations and jobs, the opportunity and freedom to interact with others (both within and across fields), and shared creativity-complementing amenities. This seems to also have been the case in early modern times. Even in 1600, creativity thrived where people came together — but especially in London’s learned societies, not the cloistered halls of Spanish convents.

Valentín Figueroa is currently an assistant professor at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. In 2025, he will join the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as an assistant professor. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from Stanford University. His website is www.valentinfigueroa.com

Buenisimo Valen!