Migration and the Making of the English Middle Class

by Vicky Fouka and Theo Serlin

When do people identify with their class? A long line of thinking from Marx and Engels to Acemoglu and Robinson assumes the answer is “always.” Nowhere was this more apparent than 19th century Europe. Elite thinkers on both the left and right believed class politics was inevitable. Lord Salisbury, the British conservative leader, thought that franchise extension in the UK was transforming politics into “a struggle between those who have, to keep what they have got, and those who have not, to get it” (quoted in Ziblatt, p 54). But these predictions turned out to be, at best, mixed. Class politics was central to electoral politics in much of twentieth-century Europe, but in a number of cases – especially the US – class politics never quite consolidated.

In a new working paper, we try to understand when people identify with their class, examining the foundational case of 19th century Britain. Our starting point is that there are many groups that people can identify with, and it is not obvious that their class is the group they will pick.

A large body of work in social psychology tries to understand when people identify with a particular group. Two of the core predictions are that people are more likely to identify with a group if it is higher in status, but they are less likely to identify with it if they are more different from its members. These insights have been incorporated into political economy by Moses Shayo.

Applying this framework to class, the prediction would be that people are less likely to identify with their class when they are culturally different from other members of the same class. If class groups are more culturally diverse, class identity should be weaker. Migration which increases the diversity of class groups should push against the formation of class politics.

The problem with testing this theory is that class identity is hard to measure. If we want to study whether changing cultural distance to the working class affects whether people identify with the working class, we would want a measure of whether they identify with the working class. Unfortunately, lots of things that do partly proxy for class identity, like the neighborhoods people live in or the schools they send their children to, are also proxies for income.

Children’s names give a relatively clean measure of class identity. The name you give your child is a free choice, both in that it is your choice, and in that it doesn’t cost anything. Class background is very predictive of the names people give their children. Accounting for factors like occupation and income, a more working class name should be more reflective of identification with the working class.

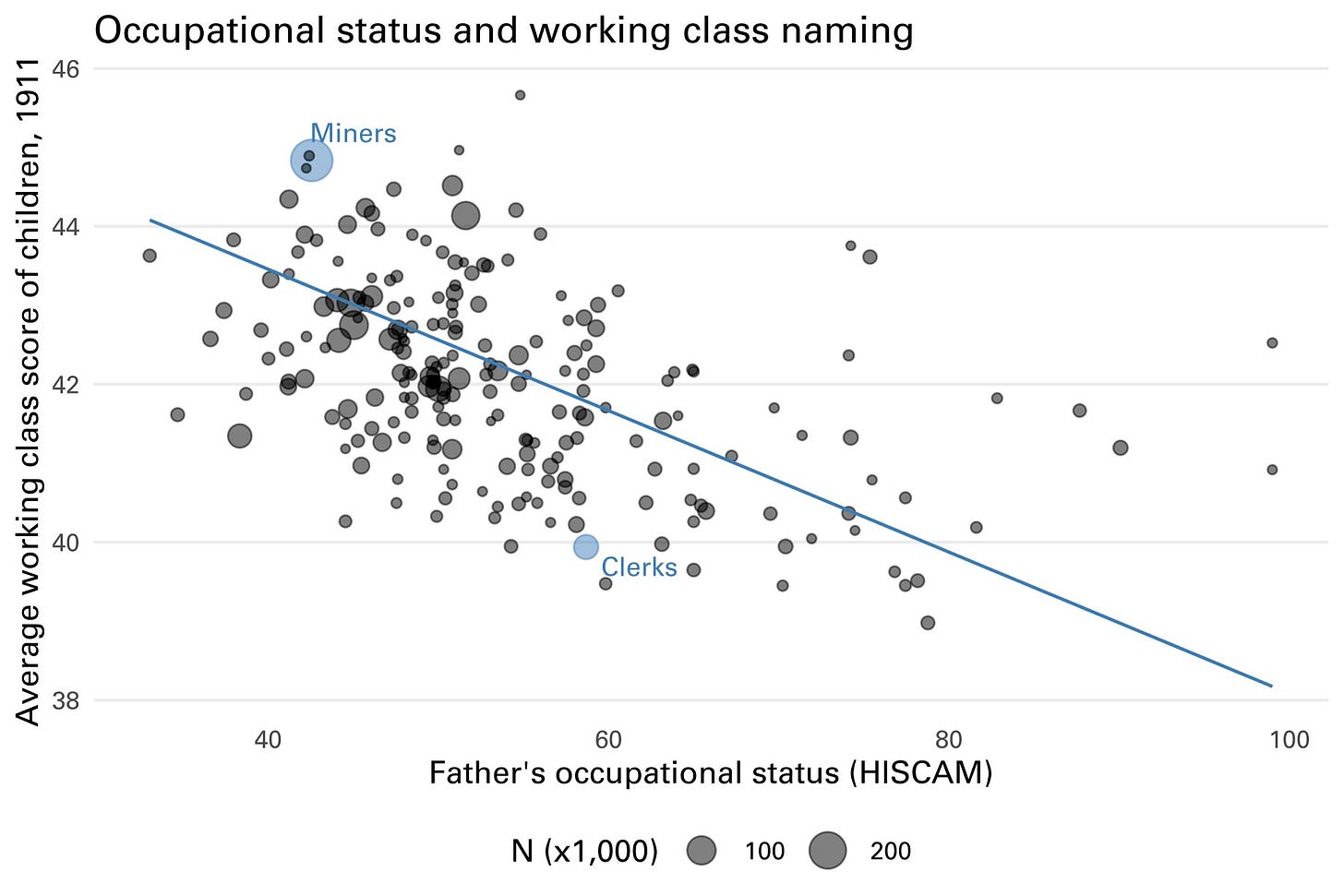

Using data on all people in the 1881 census of England and Wales, we score each name by how distinctive it is to people with occupations that were considered working class at the time, relative to those considered upper or middle class. The most working class names are Patsy, Pat, Mickel, and Bridget. The least working class are Cyril, Reginald, Cecil, and Gerald. These are the kinds of names that Oscar Wilde gave upper class characters. Calculating the scores of MPs, we see that Labour MPs and MPs affiliated with trade unions have higher scores, while aristocrats, alumni of elite schools and universities, and members of social clubs have lower scores.

The names people gave their children also reflected their class positioning. Figure 1 plots the average score for children recorded in the 1911 census against the status of their father’s occupation (using scores from the HISCAM). In general, fathers in high status occupations gave their children less working class names. But the observations off the regression line are interesting. Clerks were not particularly high status, but did not work with their hands and were considered lower middle class. They tended to give their children less working class names than other occupations of the same status.

In the census, we observe when children were born and the parish in which they were born, in addition to their names, which we use to measure class identity. Combined, this data gives us a time-stamped record of each family’s class identity and location in the year of each birth. For families with multiple children, we have multiple measures of class identity from points in time and different locations. If a family moved to a location where it was more culturally distant from the working class, we would expect that family to identify less with the working class, as measured in the names of subsequent children. Similarly, if a family lived in a location where in-migration increased the cultural distance of the average working class resident from that family, we would expect that family to identify less with the working class. Our research design effectively compares the changes in outcomes in these kinds of families, to the changes in outcomes in families that stayed in places that did not experience much in-migration.

To measure cultural distance, we construct a measure of the cultural similarity of different parishes in England and Wales for the working and upper classes, based on marriage records. The idea is that if two parishes are culturally similar, we should see more marriage between people born in the parishes. With this measure of cultural distance, and data from the census on the inhabitants and occupations of every parish and where they were born, we can measure the cultural distance between each person and the average upper or working class resident of their parish. Our focus is on average distance to the parish’s working class residents, relative to its upper class residents. We then look at how changes in this measure of distance affect class identity as measured through names.

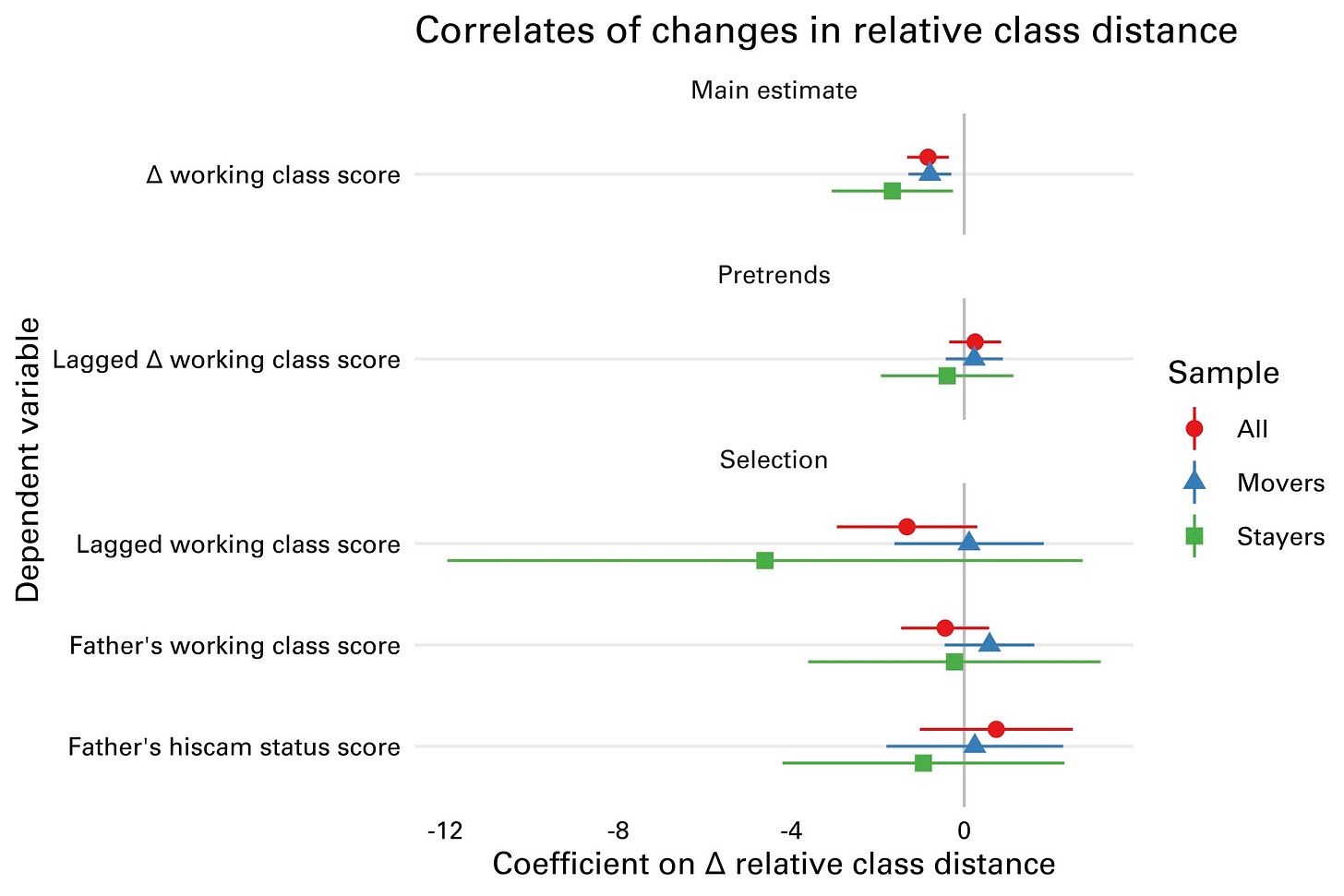

In the top row of Figure 2, we look at the relationship between the change in working class scores between two children in a household, and the change in the family’s relative distance to the working class in the birthplaces of the children, relative to the upper class. Increasing distance to the working class corresponds to a shift away from working class identity. Going from the 5th to the 95th percentile of the relative class distance distribution corresponds to a decrease in working class identity of around 11% of the difference between Oxbridge- and non-university-educated MPs. If we separate out families where the two children were born in different locations (”movers”) and those where both children were born in the same location (”stayers”) we get similar estimates. This is reassuring in that it suggests that the mechanism we want to study, and not something else that could be causing households to migrate, is driving our estimates.

To interpret this relationship as causal, we would need to believe that in the absence of the change in relative class distance, the households that experienced chages in relative class distance would have followed similar trajectories in class identity to those that did not. In the second row we look at changes in the class content of the names of the previous two children. We don’t find any evidence that households were already shifting away from the working class before they moved to locations with greater cultural distance from the working class. This helps to validate the assumption, suggesting these different groups of households were following similar trajectories before the move. We also don’t find any evidence that these different groups gave their children more or less working class names, had more or less working class names, or had more or less working class occupations before the changes in class distance due to migration.

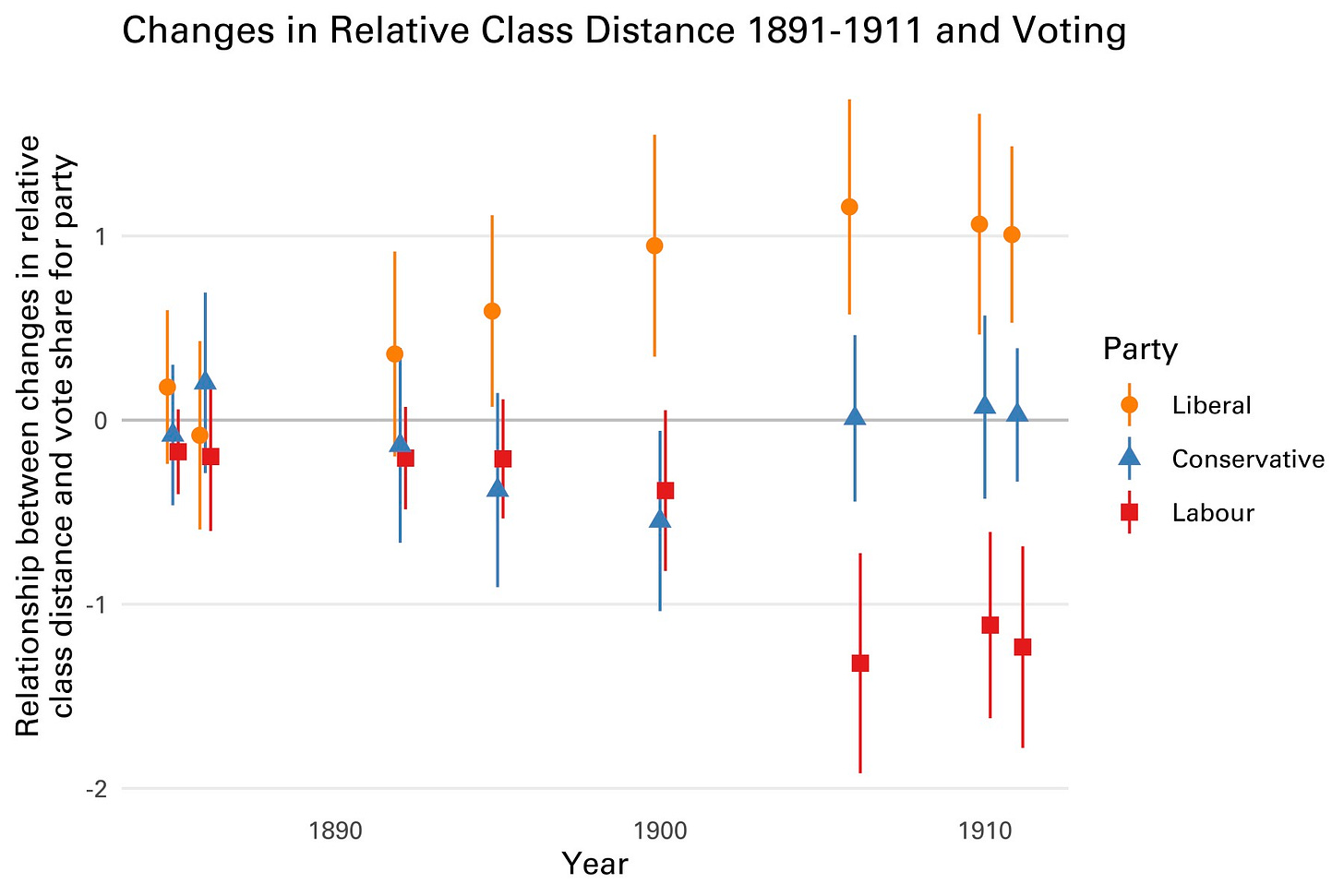

Did these changes in class identity matter for politics? If people identify less with the working class, we would expect them to be less supportive of political movements that promote the wellbeing of working class people. In late 19th century Britain, the main such movement was the Labour Party. If a place attracted lots of culturally-distant working class migrants, that would increase the average cultural distance to the working class in that place, leading people to identify less with the working class and making them less likely to vote for Labour.

In Figure 3 we examine that prediction. The figure shows the relationship between the change in relative class distance at the local level, 1891--1911, and voting for the three main parties in that area in successsive elections. In the 1880s and 1890s, the places that experienced increases in relative class distance were no more likely to vote for one party than any other. But between 1892 and 1910, these places experienced a relative shift away from Labour.

We also find evidence of politicians using rhetoric less targeted at working class voters in these areas. At the individual level, workers who were more culturally distant from the working class were less likely to join labor unions, even when comparing individuals in the same occupation in the same parish.

But what were these areas experiencing rising class distance? The main form of migration in 19th century Britain was from rural to urban areas. Peasants migrated into the cities and became industrial workers. Because of this process, by 1881, when we begin our analysis, cities had the highest cultural distance to the working class. In contrast, agricultural regions had relatively homogeneous working class populations. Over the period we study, however, these patterns reversed. In rural areas, out-migration continued, reducing the share of locally-born adults. But in urban areas working class distance actually decreased, because a growing share of the population was locally-born, the children of previous rural-urban migrants.

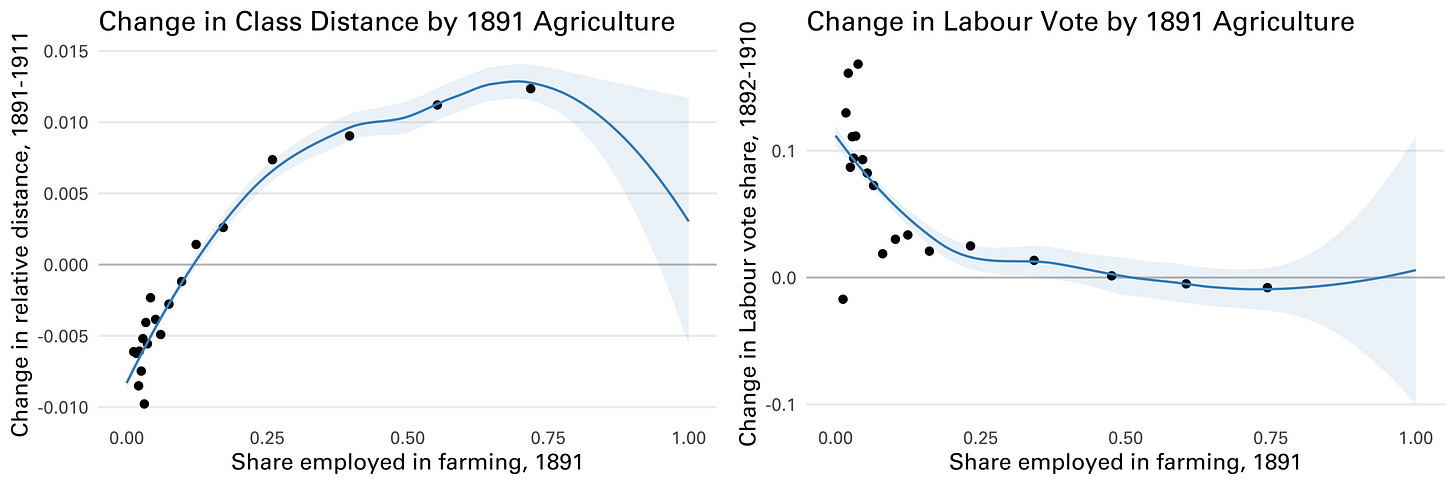

In the left panel of the figure below, we plot the (binned average) change in class distance between 1891 and 1911 against the share of employment in agriculture in 1891. Rural areas experienced an increase in relative class distance, but urban aread experienced a decrease. In the right panel we plot the change in voting for Labour against agricultural employment. The Labour Party gained votes in those urban areas which had falling class distance. Industrialization and migration first delayed and then accelerated the formation of urban working class politics in the UK.

Vicky Fouka is an associate professor of Political Science at Stanford University. She studies political economy and political behavior from a comparative and historical perspective. Her research examines what shapes social identities in the short and long run and their implications for political and economic behavior and policy design. Some topics she has focused on include immigrant integration, prejudice against ethnic and racial minorities, and intergroup conflict.

Theo Serlin is a lecturer in the department of Political Economy at King’s College London. He studies international and comparative political economy. His research integrates economic geography into political economy models of policy preferences and electoral politics. He is especially interested in the politics of trade, migration, and economic change.