Rep. James O’Hara (R-NC) and Discrimination in Interstate Travel

When the 45th Congress (1877-79) convened in October 1877, the Republicans found themselves in a vexing political situation. Reconstruction was effectively over. The Democrats controlled the House and all eleven states of the ex-Confederacy, while the GOP maintained a tenuous grip on the Senate and the presidency. Governing power was now divided between the Party of Lincoln and a resurgent white supremacist movement working through and alongside the Democrats.

The traditional claim about this era suggests that one-party Democratic rule and a Jim Crow State took hold in the ex-Confederacy immediately after Reconstruction and operated largely outside of the more democratic two-party system that otherwise functioned in the country through the 1950s and 1960s (until civil and voting rights reforms were finally instituted). This ignores a period from the late-1870s through the early-1890s – often referred to as “Redemption” – when state-level disfranchisement laws were not yet in place, Black citizens could still vote throughout the ex-Confederacy (but often faced violence and intimidation) and African Americans were still elected to Congress, and both parties vied for control of the South.[1] While the Democrats clearly had the upper hand, the Republicans periodically made real efforts to prevent the South from becoming truly “solid” for the Democrats.

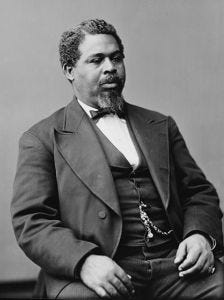

Justin Peck and I document these GOP efforts in our forthcoming book, Congress and the First Civil Rights Era, 1861-1918. I discuss one of these efforts here: in the 48th Congress, when a Black House member, James O’Hara (R-NC) – whose photo is at the top of this post – tacked an anti-discrimination amendment onto an interstate commerce bill, causing a lengthy battle over the concept of equal accommodations in interstate passenger travel.

* * * * *

In December 1884, during the lame-duck session of the 48th Congress, the House was considering a bill regulating interstate commerce. Proposed by John Reagan (D-TX), chairman of the Commerce Committee, the bill sought to place a number of limits on railroads, as a way of reducing monopolistic practices.

On December 16, as the proceedings were winding down and a vote on Reagan’s bill neared, James O’Hara, a Black freshman Republican from North Carolina, sought to add an amendment, the text of which read:

And any person or persons having purchased a ticket to be conveyed from one State to another, or paid the required fare, shall receive the same treatment and afforded equal facilities and accommodations as are furnished all others persons holding tickets of the same class without discrimination.

In proposing his amendment, O’Hara was responding, in part, to the recent Supreme Court decision in the Civil Rights Cases(1883), which deemed the Civil Rights Act of 1875 – which provided that “all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement; subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law, and applicable alike to citizens of every race and color, regardless of any previous condition of servitude” – to be unconstitutional. The Court ruled that Congress did not possess the constitutional authority under the enforcement provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to outlaw racial discrimination by private individuals and organizations– which would be necessary, given the provisions and language of the 1875 Act.[2]

Earlier in the 48th Congress, O’Hara introduced a joint resolution proposing a constitutional amendment that would have legally reinstituted the 1875 Act, safely insulated from Supreme Court challenge. But once the joint resolution was referred to the Judiciary Committee, the House took no further action on it. Recognizing that his chief goal was beyond reach, O’Hara sought to attach his amendment to the Reagan bill. It would not reestablish the provisions of the 1875 Act, but would chart a course that would be immune to Supreme Court challenge. That is, O’Hara was using the power granted to Congress to regulate interstate commerce, which was provided in Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution. Thus, the language of his amendment was tailored to address discriminatory treatment in accommodations for fares purchased for travel between states. It was thus considerably narrower than the 1875 Civil Rights Act, as it did not apply to discrimination in accommodations for travel within states. Nevertheless, O’Hara sought to accomplish what was feasible with congressional legislation, and his amendment threated to drive a racial wedge in the otherwise easy road ahead for the Reagan bill.

Having introduced his amendment, O’Hara went on to defend it. After discussing its constitutionality, per the Commerce Clause, he then laid out the issue as he saw it:

Now an evil exists, and none will deny that discriminations are made unjustly, and to a great disadvantage, between persons holding the same class of tickets who are compelled to travel on business from one State to another, and perchance across several States, en routeto their destination in another State. I therefore hold it to be not only within the power but the imperative duty of Congress to abate the evil and protect all classes of citizens from discrimination in any and every form.

That said, O’Hara took pains to frame the issue broadly:

Mr. Speaker, this is not class legislation. I do not nor would I ask such. It is not a race question, nor is it a political action. It rises far above all these. It is plain, healthy legislation, strictly in keeping with enlightened sentiment and spirit of the age in which we live; it is legislation looking to and guarding the rights of every citizen of this great Republic, however humble his station in our social scale.

The Democrats, on the verge of pushing through the Reagan bill, were taken by surprise. As the Chicago Tribune reported: “The amendment and speech [by O’Hara] seemed to paralyze Reagan.” Regaining his composure, Reagan noted that his bill was designed to regulate commerce, and that “the subject of transportation of persons” was never considered by his committee. He thus hoped the House would not enlarge the bill to include that subject at such a late date. His hopes were dashed when the O’Hara amendment passed, 134-97. Republicans voted as a bloc in support, Southern Democrats voted as a group against (with only two defections), while – critically – a majority of Northern Democrats supported the amendment. Confusion and panic set in. James H. Blount (D-GA) moved to reconsider the vote by which the amendment was agreed to, and O’Hara responded by moving to lay Blount’s motion on the table. Reagan quickly moved to adjourn, which was granted.

Reagan’s adjournment motion was strategic, as he and his supporters needed time to regroup. The O’Hara amendment put the entire interstate commerce bill at risk, and Reagan sought advice from seasoned co-partisans William Holman (D-IN) and William Morrison (D-IL) on how to proceed when the House reconvened. In the meantime, Republicans – who opposed the interstate commerce legislation – reveled in the sectional rift that O’Hara’s amendment created in the Democratic Party. When asked by a Washington Post reporter what the likely effect of the O’Hara amendment would be, Thomas B. Reed (R-ME) replied: “I think it will result in [the Reagan bill’s] defeat. It is simply another case of ‘Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion.’ Except for the drawing of the color line, the bill would have passed. Now it is not likely.”

When the House reconvened the following day, December 17, the pending question (O’Hara’s motion to table Blount’s motion to reconsider) on the Reagan bill was taken, and it passed 149-121. Once again, Republicans and Southern Democrats voted as blocs against one another. And this time, a small majority of Northern Democrats (49 of 93) voted with their Southern co-partisans in opposing the tabling motion. But a large minority aligned with the Republicans, and that was enough to table reconsideration.

Unable to reconsider the vote, the Democrats sought to try to sanitize the amendment’s content. Charles Crisp (D-GA) proposed tacking an amendment onto the end of O’Hara’s amendment: “Nothing in his act contained shall be construed as to prevent any railroad company from providing separate accommodations for white and colored persons.” Crisp went on to defend his amendment, stating that the federal court in Georgia had upheld separate accommodations under a rule of equality. Moreover, he argued that his amendment would not require companies to provide separate accommodations, but rather left that to their discretion (which they might pursue based on public sentiment). Crisp concluded by asking: “Why agitate anew this question? The law is well settled. The rights of the colored man are absolutely protected. Nobody wants to interfere with his rights. He has the same accommodations, the same kind of cars as the white man when he pays the same fare.” Robert Smalls, a Black Republican from South Carolina, responded directly to Crisp: “we have no objection to riding in a separate car when the car is of the same character as that provided for the white people to ride in. But I state here to the House that colored men and women do have trouble in riding through the State of Georgia.” He went on to describe how Black citizens traveling across states were, once in Georgia, routinely forced into second-class “Jim Crow cars.”

William C. P. Breckenridge (D-AR) then offered a substitute to Crisp’s amendment: “But nothing in this act shall be construed to deny to railroads the right to classify passengers as they may deem best for the public comfort and safety, or to relate to transportation between points wholly within the limits of one State.” As Maurine Christopher notes: “[Breckinridge’s amendment] was designed to retain discrimination in a somewhat more mannerly, less blatant fashion [than Crisp’s amendment].” In defending his amendment, Breckenridge argued that corporations (railroads) must be free to “assort passengers” from the standpoint of “public convenience and public safety,” and that O’Hara’s amendment would inject a social question into a matter of commerce (and, in doing so, impose social equality in society).[3]

In response to Breckenridge, Thomas Reed gained the floor and shared with the House an example of his sardonic wit:

Mr. Speaker, I must say that I rejoice to see this question lifted by the last suggestion from a mere question of politics or of color. I did not propose to discuss it in that light. I thought it very desirable that we should have a vote on the main question without bringing up questions of color or stirring up feelings of race or partisanship. Let wisdom be justified of her children. So I am very much pleased, indeed, to see this amendment of the gentleman from Arkansas. This at once ceases to be a question of politics or color, and has now become a question of assortment [laughter]; and now, this House, which is determined to pursue these “robber barons,” has before it the plain question whether it will not merely leave to them the privilege of assorting us, but whether it will absolutely confer upon them the privilege of assortment by direct enactment on the part of Congress. [Renewed laughter.]

Now I appeal to this House, engaged as it in the pursuit of wicked monopolists, if it intends to confer upon them a privilege of assortment without rights of law? Why, surely we must have some Treasury regulations as to the method of assortment. [Laughter.] Are we to be assorted on the grounds of size? [Great laughter.] Am I to be put into one car because of my size and the gentleman from Arkansas into another because of his? [Renewed laughter and applause.] Is this to be done on account of our unfortunate difference of measurement? Or are we to be assorted on the moustache grounds? Are we to be assorted on the question of complexion, or are we to be assorted on the beard basis?

If not any of these, what basis of assortment are we to have? For my part I object to having these “robber barons” overlook and assort us on any whimsical basis they undertake to set up. [Laughter.]

Why, surely, Mr. Speaker, this House, engaged as it in putting down discriminations against good men, can not tolerate an amendment of this character for an instant. [Applause.]

Reagan responded by referring to Reed as “facetious,” and argued that railroad conductors by “universal practice” possessed the power to sort people, so as, for example, to keep a “drunken man or a rowdy or a desperado” out of “a lady’s car.” Further, he asked: “Now, does the gentleman insist on his humor in getting up a laugh about assorting people, or does he wish to pile all sorts of people and all classes into the same car?” Moreover, Reagan stated that he attached “no importance to [O’Hara’s amendment],” as “it simply reaffirms the common law and the law and the practice in every Southern State in this Union.”

A short but spirited debate then ensued as to what the intent and consequences of the O’Hara amendment actually were. Crisp suggested the amendment’s purpose was “to prevent a separation of the colors” (or to desegregate accommodations in interstate travel). Barclay Henley (D-CA) remarked that he was not sure as to O’Hara’s intent, but believed that the “the introduction of this race question, this social question, … was seized upon by the other side and taken up for the purpose … of defeating [the Reagan bill], a bill designed to relieve the people of this great Republic against the exactions and aggressions of the railroad companies.” Ethelbert Barksdale (D-MS) asserted that he would vote for the Reagan bill, even encumbered with the O’Hara amendment, as he felt that the amendment’s provisions “[do] not prevent railroad companies from providing separate accommodations for persons, provided they are equally comfortable.” Thomas Browne (R-IN) spoke more broadly, arguing that “emancipation, citizenship, and enfranchisement have come, and the social relations between races continue, as they were, a matter of personal choice,”[4] but that the current question was not a social question but rather one of commerce: “It is a question between common carriers, engaged in transportation of passengers for hire and exacting particular fare in return of particular accommodations agreed to be furnished by them and the passenger. That is the contract.”

Finally, the question of adopting the Breckenridge substitute (in lieu of the Crisp amendment) was before the House. It was defeated on an 80-111 division vote, after which Holman demanded the yeas and nays. After some parliamentary back-and-forth, the yeas and nays were called, and the result flipped – as the Breckenridge substitute was adopted 137-127. Most Northern Democrats joined with almost all Southern Democrats to oppose and defeat the mass of Republicans. The House then moved to consider the Breckenridge substitute as an amendment to the O’Hara amendment, and it passed – first on a 148-117 division vote and then on a 137-131 roll call (after Reed demanded the yeas and nays). Again, most Northern Democrats joined with all Southern Democrats to defeat a unified bloc of Republicans.

Thus, the Democrats had succeeded in granting railroads the discretion “to classify passengers” as they deemed fit. This was a clear victory. But if Democratic leaders felt that they were in the clear, they were mistaken. Nathan Goff, Jr. (R-WV) was recognized and sought to add the following to the end of the Breckenridge substitute: “Provided, That no discrimination is made on account of race or color.” A roll call followed, and the Goff amendment passed, 141-102. A small majority of Northern Democrats now joined with all Republicans to defeat a near-unified group of Southern Democrats. Goff then moved to reconsider the move, and also to lay the motion to reconsider on the table – but Reagan pushed for adjournment, which was granted. As was the case from the day before, Reagan needed to regroup, as his interstate commerce bill (now with Goff’s amendment attached) was once again in danger.

The following day, Goff’s tabling motion was considered and passed, first on an 87-77 division vote and then on a 140-108 roll call (after Reagan demanded the yeas and nays). All Republicans joined with a minority of Northern Democrats to defeat a near-unified group of Southern Democrats. Thus, the motion to reconsider the vote on the Goff amendment was laid on the table. The pro-discrimination Democrats now turned to negating the impact of the Goff amendment. Here, Barksdale reentered the fray by moving an amendment to the Goff amendment, which would add the following words (as a clause) after the word “color”: “And that furnishing separate accommodations, with equal facilities and equal comfort, at the same charges, shall not be considered a discrimination.” Barksdale’s amendment passed, first 112-81 on a division vote and then 132-124 on a roll call (after Republican Roswell Horr of Michigan demanded the yeas and nays). Barksdale then moved to reconsider the vote by which his amendment was adopted, and to lay the motion to reconsider on the table – and it was agreed to. The anti-discrimination forces would make one last push, as Horr moved an amendment to the Barksdale amendment, which would add the following words (as a clause) after the word “discrimination”: “Provided, That such separation shall not be made on the basis of race or color.” Horr’s amendment failed 114-121 on a roll call, with a larger proportion of Northern Democrats (than on previous votes) joining with all Southern Democrats to oppose all Republicans.

With the defeat of the Horr amendment, the matter of race, discrimination, and accommodations in interstate travel was settled.[5] Eventually, on January 8, 1885, the House would pass the Reagan bill, 161-75. However, the Senate would not agree – passing instead a bill endorsed by Shelby Cullom (R-IL), which called for a regulatory commission (and thus was similar to a bill that Reagan had earlier pushed aside in the House). Eventually, a bill was agreed to (in conference) in the 49th Congress (1885-87), which included both a commission (a demand of Cullom’s) and an anti-pooling provision (a demand of Reagan’s), among other compromises, and it was enacted into law on February 4, 1887, during the lame-duck session. The Interstate Commerce Act made no specific mention of race, but instead included (in Section 3) somewhat ambiguous language regarding what constituted discriminatory behavior by railroads:

It shall be unlawful for any common carrier subject to the provisions of this part to make, give, or cause any undue or unreasonable preference or advantage to any particular person, company, firm, corporation, association, locality, port, port district, gateway, transit point, region, district, territory, or any particular description of traffic, in any respect whatsoever; or to subject any particular person, company, firm, corporation, association, locality, port, port district, gateway, transit point, region, district, territory, or any particular description of traffic to any undue or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever.

For this, O’Hara no doubt deserves credit, as there was no attempt to speak to the nature of personal accommodations in interstate commerce before he offered his amendment in late-1884. And the Section 3 provision would form the foundation of anti-discrimination rulings – in response to acts of racial segregation in train and bus service, in keeping with state code – by the Supreme Court decades later in Mitchell v. United States (1941), Morgan v. Virginia (1946), Henderson v. United States (1950), Keys v. Carolina Coach Co. (1955), and Boyton v. Virginia (1960).[6] In 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), at the behest of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, would require all interstate bus companies to display the following message in all their buses: “Seating aboard this vehicle is without regard to race, color, creed, or national origin, by order of the Interstate Commerce Commission.”

[1] For example, eight African Americans served in the U.S. House from the 47th (1881-83) through 56th (1899-1901) Congresses: John Lynch (R-MS), 47th; Robert Smalls (R-SC), 47th-49th; James E. O’Hara (R-NC), 48th-49th; Henry P. Cheatham (R-NC), 51st-52nd; John Mercer Langston (R-VA), 51st; Thomas E. Miller (R-SC), 51st; George W. Murray (R-SC), 53rd-54th; and George H. White (R-NC), 55th-56th.

[2] Rather, per the Court’s ruling, the enforcement provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment applied only to discriminatory behavior undertaken by state and local governments.

[3] Here, Breckenridge harkened back to the Supreme Court-repudiated Civil Rights Act of 1875, which Southerners often called the “social equality bill.”

[4] Browne went on to tweak the Democrats regarding their fear of race-based social-equality laws: “Gentlemen do not seem to know that this question of social life is not, never was, and never can be regulated by law. It is a question of individual tastes. I associate with gentlemen because I believe them to be my social equals. I decline to associate with other gentlemen, whether they be white or black, because I do not so regard them. If this was a statute to make a colored Republican equal to a white Democrat I should vote against it. I would not vote for it. It could not be possible either to reduce the one or to elevate the other by an act of Congress. [Laughter.]” See Congressioinal Record, 48-2, 12/17/1884, 320.

[5] One question that permeates the entirety of the O’Hara amendment episode is: why did a significant number of Northern Democrats – and sometimes a majority – join with Republicans in support of civil rights legislation that was anathema to their Southern co-partisans? According to David Bateman, Ira Katznelson, and John Lapinski, “Although there were probably some Democrats, North and South, who supported the amendment in order to kill the bill, contemporaries mostly understood the northern Democratic support as an extension of their recent efforts during the 1884 presidential campaign to cultivate support among northern black voters.” In fact, while Southern Democrats routinely used violence and intimidation against Black citizens in the former-Confederacy, Northern Democrats since 1873 had been reaching out – often with little to show for their efforts, but with occasional successes – to Black voters in their localities. For a detailed discussion of Northern Democrats’ efforts between 1873 and 1892 in this regard, see Lawrence Grossman, The Democratic Party and the Negro: Northern and National Politics, 1868-92 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1972), 60-106.

[6] Derek Charles Catsam, Freedom’s Main Line: The Journey of Reconciliation and the Freedom Rides (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2009). The Court’s rulings in the Mitchell and Henderson cases overturned initial ICC decisions that favored the interstate carriers.