Stalin's Famine

by Natalya Naumenko (GMU)

The 1933 Soviet famine killed 6 to 10 million people; 60 million starved or witnessed starvation but survived, probably scarred for life. This famine was the second-largest in 20th-century history, after the Great Chinese famine; by the proportion of deaths to population, it was similar to it. 1933 seems far away, but we are talking about our grandparents and great-grandparents living through unimaginable horrors: whole villages depopulated, cannibalism.

Disproportionately many of the victims were Ukrainians: the Soviet republic of Ukraine was just 20% of the population, but accounted for at least 40% of the famine deaths. Ukraine considers the 1933 famine a genocide, while Russia claims that Stalin was “an effective manager” and destroys famine memorials in the occupied territories. The memory of the famine and suffering affects politics and economic development to this day (Rozenas and Zhukov, 2019; Yaremko, 2022; Naumenko, 2024b).

This post summarizes the research Andrei Markevich, Nancy Qian, and I have published studying this famine (Naumenko, 2021; Markevich, Naumenko, and Qian, 2024). The maps below show the distribution of ethnic Ukrainians and 1933 excess mortality; higher mortality occurred where more Ukrainians were present. However, there is still a debate: is this because ethnic Ukrainians were targeted, maybe even by an artificially planned and organized famine, as some claim, or because Ukrainians happened to live in grain-producing areas of the Soviet Union, and grain-producing areas suffered, either from bad weather or bad government policies?

To answer this question, we must take a step back and understand why this famine happened.

Famines in Russian history

First, let’s put the 1933 famine in perspective. How normal, or how abnormal, was it? Russia (the Russian Empire before 1917, the Soviet Union after 1917) was a largely agrarian economy: in 1926, 80% of the population were peasants, and agriculture was roughly 50% of GDP (Cheremukhin et al., 2016). Compared to Europe and the US, agriculture was less productive (Allen, 2003), but after the abolition of serfdom in 1861, yields were increasing steadily until 1913 (Markevich and Zhuravskaya, 2018). World War I, the 1917 Revolution, and the subsequent Civil War interrupted this process; however, by 1928, the rural economy had roughly recovered to the level of 1913 (Markevich and Harrison, 2011). Before 1933, in recent Russian history, there were two large rural famines: in 1892 and in 1922.

The 1892 famine was caused by a severe 1891 drought and was exacerbated by a cholera epidemic; its epicenter was in the fertile but drought-prone Volga region in the south of Russia. This famine killed roughly 0.5 million people (Wheatcroft, 1992).

Civil War destruction and arbitrary grain requisitions during the War Communism era (1918–1921) reduced land under cultivation by more than 30%. A severe 1921 drought with its epicenter in the Volga region further exacerbated the crisis. It is difficult to separate the 1922 famine victims from the WWI and Civil War losses, but estimates range from 3 to 5 million (Adamets, 2003; Wheatcroft, 2017).

Thus, the 1933 famine was unprecedented: without war destruction, with no worse agricultural technology than in 1891, it killed an order of magnitude more people. Moreover, the mortality epicenter was different: in Ukraine, as opposed to the Volga region. Was the weather ten times worse than in 1891? Did something else cause the famine?

Collectivization

In late 1929, Stalin started a comprehensive collectivization campaign. According to official documents, grain-producing southern areas were the first priority for collectivization, while the less-productive north was less of a priority. Under collectivization, peasants were forced to give up their land, livestock, and implements and to work together on collective farms. The harvested grain was put in collective farm granaries, where, after giving the government its share and setting aside seed stocks, fodder, and reserves, the rest was to be divided among the collective farm members. The government tried to prevent collective farm members from keeping private plots and livestock; whatever was left in private property was insufficient for subsistence. Trading of food was banned, and the government used procured grain to feed the urban population and for export.

Collectivization simplified the extraction of grain from the countryside: it is easier to search one collective farm granary instead of a hundred individual households. This essentially meant that the government could put a 100% tax on surplus grain. Historians generally agree that collectivization also destroyed incentives to work: why produce more than subsistence if all surplus is taken away? Consequently, in 1931 and especially in 1932, harvests were lower than the government had planned.

Food Accounting

But was the 1932 harvest decline bad enough to kill millions? The figure below plots grain production from 1913 to 1939 in constant Soviet borders.

Two observations are striking. First, the 1932 harvest is almost twice as large as the 1921 harvest. How is it possible, then, that the 1933 famine had more victims? Second, the 1932 harvest is similar to the 1936 harvest, but there was no mass starvation in 1937. Thus, arguing that there was not enough grain in the country to prevent mass casualties—that, essentially, someone had to die in 1933—is unsound. Moreover, even if we attribute the harvest decline to weather (which I disagree with), weather could not be the main cause of famine; the harvest decline was not bad enough. Somehow, the system of collectivized agriculture-procurement-distribution turned a low harvest into a catastrophe.

Of course, what matters is not only the total amount of grain, but also how it is distributed in the country. Maybe some areas produced too little, and the government tried to help but failed? Markevich, Naumenko, and Qian (2024) show that Ukraine produced less than usual, but this low harvest would have been enough to avoid mass casualties had the government not taken away more than 40%. Consistent with the harvest totals presented in Figure 3, they also argue that the grain taken from Ukraine was not necessary to prevent mass starvation in the rest of the Soviet Union.

Causes of the 1933 famine

Why then did millions die in 1933, both in Ukraine and outside? Here’s what I think happened.

First, collectivization led to a harvest drop, especially in traditionally productive areas that were more intensely collectivized, including Ukraine. Then, insisting that the peasants were sabotaging collectivization and hiding grain, Stalin pushed ahead with procurement, turning a bad harvest into a catastrophe. Grain procurement again targeted areas that usually produced more grain, both because it was difficult for the government to assess how little grain was actually there in 1932, and because it was easier to take grain from more collectivized areas.

Consistent with this explanation, Naumenko (2021) shows that, in Ukraine, harvest drop is not predicted by the weather—therefore, it must have been caused by collectivization. Naumenko (2021) also shows that within Ukraine, districts (relatively small administrative units) with a higher collectivization rate (measured in 1930 or in 1932) experienced higher famine mortality. That is, if you compare districts with similar agroclimatic conditions, similar past productivity, and similar 1932 weather, the more collectivized ones on average suffered more in 1933.

Also consistent with this explanation, using a sample of provinces (relatively large administrative units), Markevich, Naumenko, and Qian (2024) show that 1932 grain production is either unrelated to famine mortality or is positively correlated with it. Had there been a simple harvest failure not exacerbated by procurement, we should see a negative correlation: lower harvest would lead to more deaths. A zero or positive correlation occurred because the government overprocured from the areas that experienced harvest decline relative to normal years but still produced more grain than the North.

The famine was created by government policies, but this does not mean that the famine was created intentionally. Rather, the ban on trade prevented places with food to spare from selling it—if you revealed that you had more than the government suspected, more than enough for subsistence, you would be targeted by harsher collectivization and grain collections next. The government, frantically trying to feed the urban population and not able to collect as much grain as it had planned from traditionally productive areas, left them without subsistence.

Already in 1932, it was obvious that the system was not working. After the famine, procurement quotas were linked to farms’ assigned sown area and thus were made more predictable. Collective farm members were allowed and even encouraged to keep private livestock and gardens (although these were heavily taxed). After paying taxes and delivering the assigned quotas, peasants could sell the remaining produce in markets at free prices. Peasants received most of their income from private plots and livestock and worked in collective farms primarily for the right to keep them (Belov, 1956). Collectivization continued and, eventually, all peasants were collectivized, but this private sector afforded subsistence.

Bias against Ukrainians

If the famine was created by policies (collectivization and procurement) that targeted grain-productive areas, did Ukrainians suffer simply because they lived in productive areas? No. Every policy we can measure was implemented with a bias against ethnic Ukrainians, resulting in severely biased famine mortality.

First, using a sample of districts in Ukraine, Naumenko (2021) shows that from the start of the collectivization campaign, ethnic Ukrainian areas were collectivized more intensely. That is, if you compare districts with similar agroclimatic conditions and similar past productivity, the ones with a higher share of ethnic Ukrainians were, on average, more collectivized in 1930.

Second, using a sample of provinces, Markevich, Naumenko, and Qian (2024) show that 1932 procurement was more intense in areas with a higher share of ethnic Ukrainians. That is, if you compare provinces with similar harvests, on average, more grain was taken from the ones with more ethnic Ukrainians. This resulted in a bias in grain retention (production minus procurement): provinces with more ethnic Ukrainians were left with less food after the 1932 harvest.

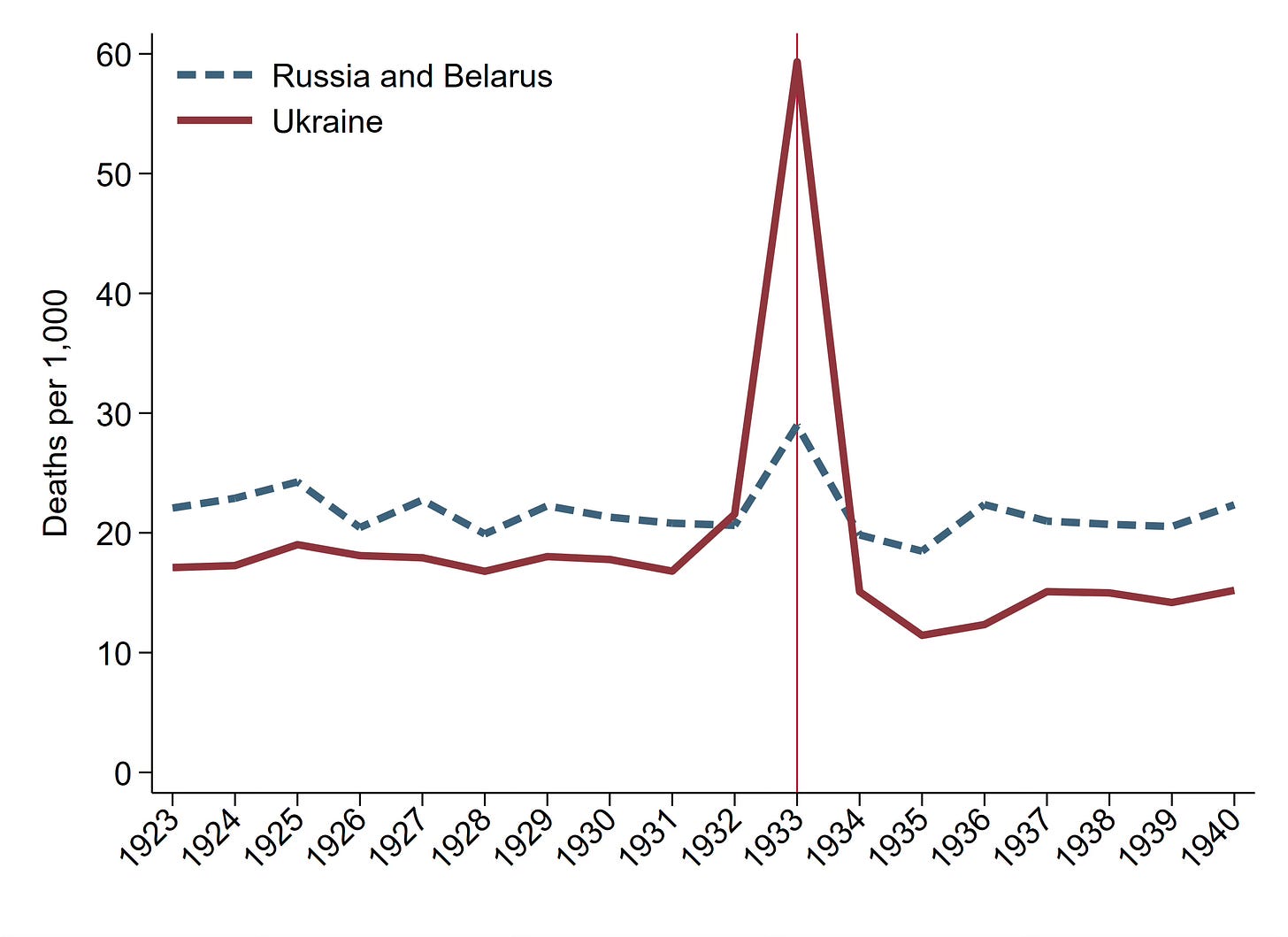

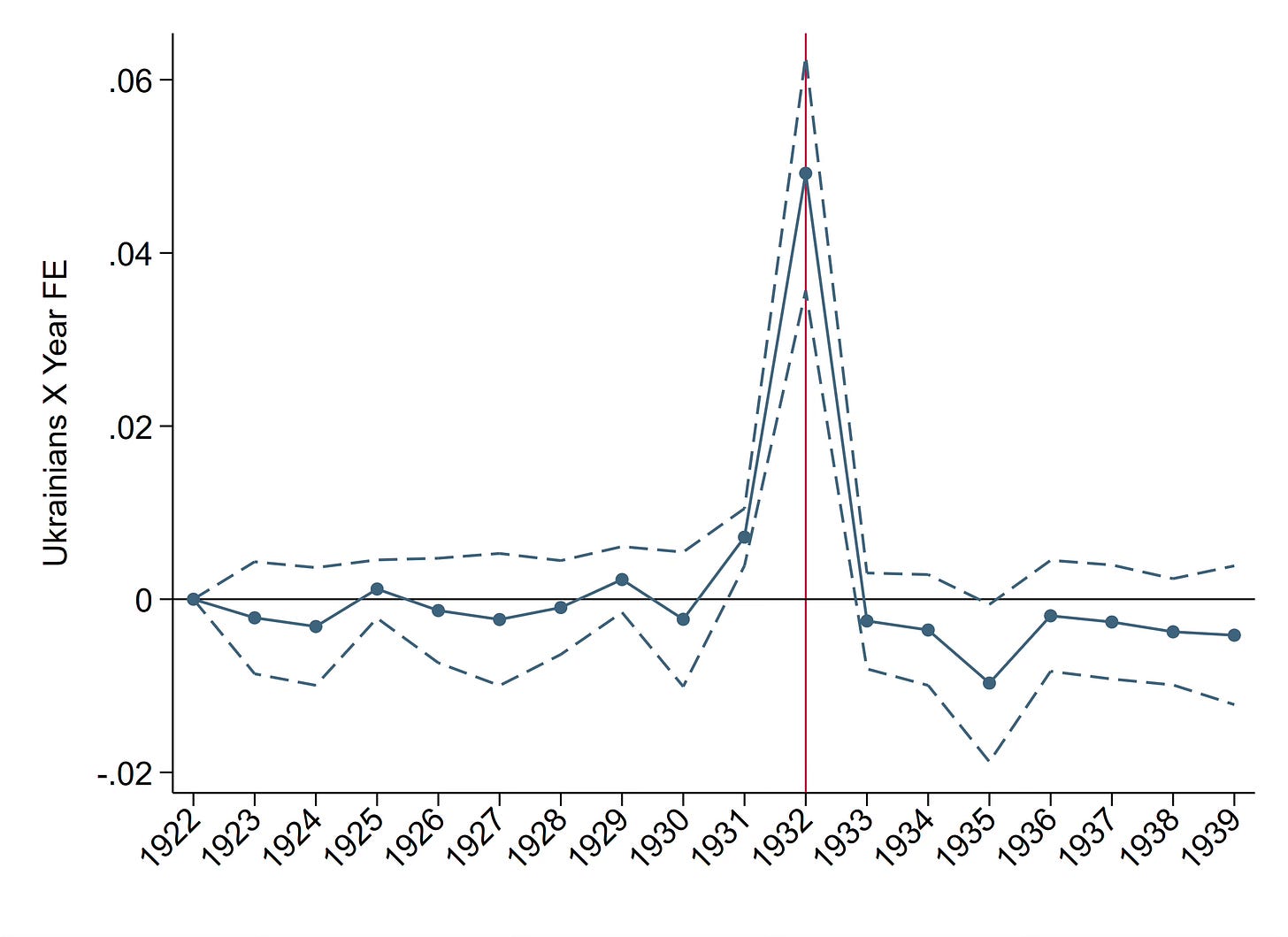

Consequently, using both a sample of provinces and districts within provinces, Markevich, Naumenko, and Qian (2024) show that famine mortality was biased against ethnic Ukrainians. That is, if you compare provinces with similar harvests, similar weather, and other characteristics, the ones with more Ukrainians on average had higher famine mortality. To illustrate this, Figure 4 plots average mortality from 1923 to 1940 in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus: Ukraine experienced a much larger spike in 1933. Figure 5 plots the estimated difference in mortality between Ukrainian and non-Ukrainian provinces after each harvest from 1922 to 1939. This difference remained stable until the harvest of 1931. In 1932 (after the 1931 harvest), Ukrainian areas experienced higher mortality; in 1933 (after the 1932 harvest), the difference was huge. On average, if you move from a province with zero Ukrainians to a province with 100% Ukrainians, famine mortality increased by 50 per 1,000; this is huge given that normal non-famine mortality was around 20 per 1,000.

Markevich, Naumenko, and Qian (2024) show that, similar to provinces, if you compare districts within the same province with similar soil quality and 1932 weather, the ones with more ethnic Ukrainians had higher famine mortality. Moreover, this is true even if we drop Ukraine from the sample and only consider Russia and Belarus—there appears to have been a pervasive bias against ethnic Ukrainians, not just against the Ukrainian Republic.

Finally, Markevich, Naumenko, and Qian (2024) show that, conditional on production, the First Five-Year Plan was planning to procure slightly more from ethnic Ukrainian territories. This does not mean that Stalin planned to create the famine or to starve Ukrainians; rather, it made Ukrainians more vulnerable if the harvest was below the planned level.

Statistical methods do not allow us to attribute the bias. Whether it was driven by local officials or by Stalin and the Politburo, or some combination of the two, we cannot tell. We do know that ethnicity was salient at the time, that in 1918 Ukraine briefly tried to declare independence from Russia, that Stalin worried about “losing Ukraine,” and that Ukrainians were perceived as more resistant to collectivization. We do know that procurement targets and how strongly they were enforced were decided in Moscow. Yet there is no “smoking gun” document where Stalin spells out an intention to target a specific ethnic group. With or without this intention, the result was a devastating famine that killed millions but hit Ukrainians particularly strongly. Nothing can bring back the dead, but we hope this work moves us closer to historical justice.

Author

Natalya Naumenko is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics at George Mason University. Her research concentrates on economic history and political economy, with a particular focus on Russia and the former Soviet Union. She graduated from Northwestern University in 2018. Before joining Mason, Naumenko was a postdoc at the Political Theory Project at Brown University. Her website is here.

China made the same mistake during the Great Leap Forward. And they mostly killed a bunch of Chinese. Perhaps if we dig into it we’d find that particular subgroups died at greater rates and that may or may not just be a residual correlation with other factors. But I think that misses the big picture.

Nobody wanted millions to starve in either case. It doesn’t strike me as “the plan”. Once people start starving you’re going to end up with a bunch of patterns, but that doesn’t mean starvation was the goal.

Good job on the ReStud