The Social Origins of Democracy and Authoritarianism Reconsidered: Prussia and Sweden in Comparison

by Erik Bengtsson and Felix Kersting

Why do some countries democratize while others descend into authoritarianism? One of the most enduring answers to this question centers on the political economy of land. The classic view in political science and historical political economy holds that in societies where powerful rural elites dominate the countryside, democratization is less likely to succeed. Landed elites, the argument goes, are hostile to mass suffrage and liberal politics, and use their social and economic power to block or roll back democratic reforms.

Germany has long been considered the prime example of this model. From Barrington Moore’s landmark study Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy in the late 1960s to recent work in political science (Ziblatt 2008, Montalbo 2023, Emmenegger et al. 2024), the story has remained consistent: the strength of aristocratic landowners in rural Prussia underpinned conservative authoritarianism and helped doom the Weimar Republic.

But does this contrast hold up? And does rural inequality always breed authoritarianism? In new research (Bengtsson and Kersting 2025), we revisit these questions with a different perspective. Rather than seeing land inequality solely as a source of elite repression, we consider an alternative tradition, building on scholars such as Dietrich Rueschemeyer, Evelyn Huber Stevens, and John D. Stepens in Capitalist Development and Democracy (1992) and Gregory Luebbert in Liberalism, Fascism, or Social Democracy (1991). In our framework, building on these works and others, stark disparities in rural wealth can trigger class conflict and radicalization—particularly if landowners fail to exercise social control over laborers and peasants. Where elite hegemony is weak, inequality may generate not passivity but politicization, feeding the growth of the organized Left.

To test these competing ideas, we turn to two canonical cases: Germany and Sweden in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Germany is the country case par excellence of the landlordism-authoritarianism model, while the less studied Sweden typically in comparisons is portrayed as a relatively egalitarian, farmer-dominated society which managed a peaceful transition to democracy and forged enduring class compromises. Thus, these two countries are often seen as opposites, both in terms of social structure and political development.

Land inequality in Prussia and Sweden

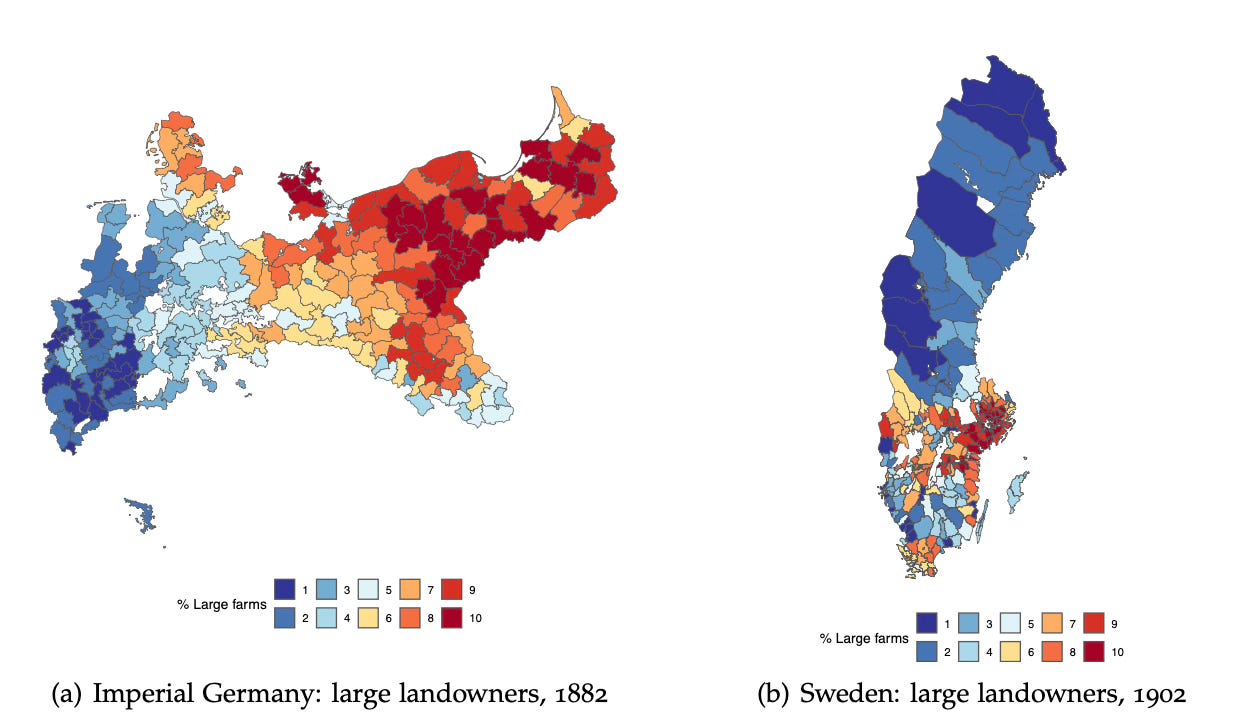

To begin with, we revisit the basic empirical assumption that underpins most of the historical narrative: that Sweden had a more equal agrarian structure than Germany. This assumption is widespread across both historical and political science literatures. Yet the data tell a different story. Using detailed historical records, we compare landholding structures in Sweden (1902) and Prussia (1882). One common indicator of landlord dominance is the share of farms larger than 100 hectares (shown in Figure 1). By this measure, Sweden was not less unequal than Prussia; if anything, it was slightly more so. Comparisons on other indicators, such as the Gini coefficient of land ownership, reinforce this view. In the decades around 1900, the Swedish countryside was not an egalitarian exception but part of a broader European pattern of agrarian inequality. This finding is in line with other recent research investigating income inequality. These findings are important in their own right, as they call into question a central tenet of received wisdom. But what matters more is how this inequality translated into political behavior.

Land inequality and political outcomes

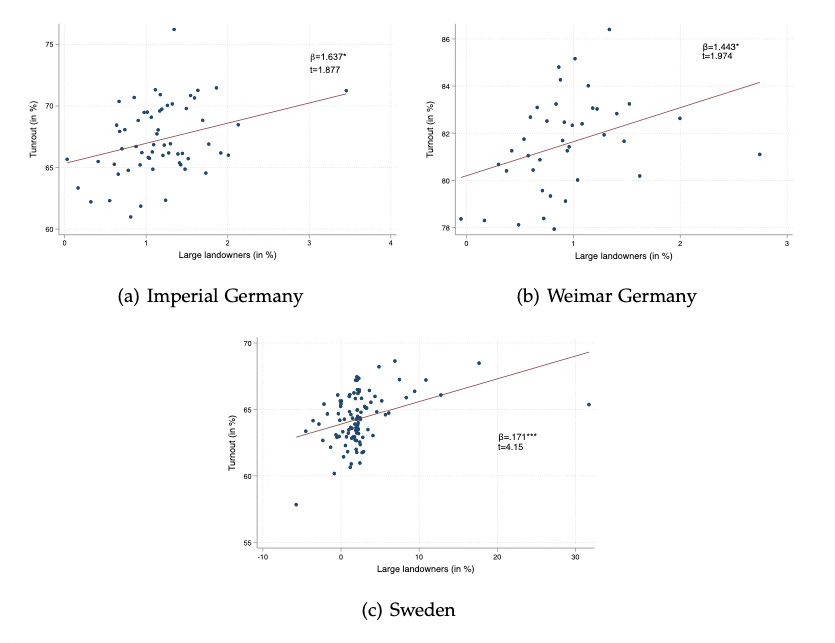

If the classic landlord-dominance theory is correct, we should expect that more unequal areas would have higher support for conservative parties, lower support for democratic or leftist parties, and lower voter turnout—reflecting social control by landlords and political exclusion of the working class. But when we look at the data from Germany and Sweden, we find almost the exact opposite.

We examine how land inequality relates to three political outcomes: vote shares for conservative parties, vote shares for Nazi parties, and voter turnout. Using a repeated cross-section model, we regress these outcomes on land inequality, controlling for agricultural employment (to account for rural structure) and other confounders. Election fixed effects account for national trends, and province or county fixed effects address unobserved regional differences. Our main coefficient captures the association between land inequality and political behavior, with robustness checks including controls for soil quality and agricultural productivity.

In Prussia, electoral support for the conservative party was not higher in more unequal rural areas. In Sweden, conservative parties were weaker in districts with greater land inequality. In both countries, land inequality was positively associated with voter turnout—suggesting that political engagement, not apathy or repression, was higher where rural elites were stronger on paper (see Figure 2).

Towards some explanations

This pattern points toward a different political dynamic: one in which inequality fueled popular mobilization rather than elite domination. In Sweden, this dynamic is especially clear. Areas with higher land inequality also saw higher rates of trade union membership, greater support for Socialist parties, and stronger turnout among laborers. Far from being politically dormant, these regions were strongholds of left-wing mobilization. The sharp class divisions created by inequality appear to have politicized rural workers, pushing them into the electoral arena and into labor organizations.

In Prussia, the mechanisms seem somewhat different. Rather than organizing politically, many workers appear to have responded to inequality through migration. Counties with higher levels of land concentration had higher rates of out-migration, especially to urban areas and abroad. In effect, people resisted landlord power not by voting against it, but by leaving. This “exit” pattern weakened the social base of rural elites and reduced their long-term political influence.

Implications

These findings complicate the standard narrative that links rural inequality to authoritarianism. If anything, they suggest that land inequality did not translate to higher levels of anti-democratic attitudes. The persistence of authoritarianism in Germany, or the absence of it in Sweden, cannot be fully explained by differences in landholding patterns. What mattered more was - as suggested previously for example by Daniel Ziblatt’s comparison of Conservative parties in Britain and Germany (Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy, 2017) - how political institutions shaped and channeled the effects of inequality—either into democratic mobilization or into breakdown and conflict.

What does all this mean for how we think about landlords and democracy? At a minimum, our findings challenge the idea that landlord dominance inevitably erodes democratic prospects. While classic theories have portrayed powerful rural elites as obstacles to democracy, our analysis suggests the relationship is more complex. Agrarian inequality does not mechanically translate into political repression or authoritarian sentiment. In fact, in both Sweden and Germany, the most unequal areas often displayed signs of political engagement—whether through mobilization, resistance, or migration. These dynamics complicate the simple story that inequality breeds authoritarianism and point instead to a more contingent, context-dependent relationship between rural class structure and political development.

Of course, our study focuses specifically on electoral politics and mass political behavior. We do not examine other important aspects of elite influence, such as control over the bureaucracy, the military, or the judiciary—dimensions that have long been central to accounts of Germany’s so-called Sonderweg. These elements of aristocratic power deserve further scrutiny. But we would argue that electoral politics remains a vital part of the puzzle, especially in light of the growing literature in historical political economy that places voting behavior and referendums at the center of analysis. When it comes to understanding how land inequality shapes democracy from below, it is crucial to study not just what elites do, but how ordinary people respond.

Ultimately, our results call for a more nuanced model of how rural inequality feeds into political life. As scholars like Luebbert have long argued, economic control does not automatically equal political control. Whether landlords succeed in shaping outcomes depends on the strategies they pursue, the openness of institutions, and the capacity of other actors—especially the working class—to organize and push back. In this light, the comparison between Sweden and Germany offers a striking lesson: similar rural structures can produce different political trajectories. What made the difference was not land inequality itself, but how it was mediated by institutions, historical legacies, and bottom-up mobilization.

Authors

Erik Bengtsson is senior lecturer at the University of Lund. His website is https://sites.google.com/view/bengtsson/start

Felix Kersting is a Postdoctoral Researcher at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. His website is https://felixkersting.mystrikingly.com/

# The Left's Inequality Paradox: Heads I Win, Tails You Lose

Left-wing political movements have developed a remarkably convenient theoretical framework that justifies their ascendancy regardless of economic conditions. This intellectual sleight-of-hand deserves closer examination.

When inequality is high, left-wing parties claim electoral inevitability because redistribution becomes necessary. The logic seems straightforward: growing disparities create demand for policies that address economic imbalances, naturally favoring parties that promise redistributive solutions.

Conversely, when inequality is low, these same parties argue they should win because an empowered working class will refuse to let capitalists exploit them. In this formulation, reduced inequality doesn't diminish the need for left-wing governance—it actually strengthens workers' capacity to demand continued protection from market forces.

This creates a perfect logical trap: apparently no level of inequality exists where left-wing parties should lose power or where less redistribution might be appropriate. The framework immunizes left-wing politics against empirical contradiction by ensuring that any economic outcome validates their continued relevance.

The conventional wisdom about Sweden illustrates this perfectly. The thesis that higher inequality motivated the political success of left-wing parties makes intuitive sense—economic disparities created constituency demand for redistributive policies. This represents a logical connection between economic conditions and political preferences.

What seems bizarre is the opposite theory becoming accepted wisdom. If inequality were genuinely low, the most successful political movements should logically center around middle-class values like classical liberalism rather than working-class grievances. In a more equal society, the political focus should shift toward protecting individual opportunity and limiting government overreach, not expanding redistributive mechanisms.

The persistence of this paradox reveals how ideological frameworks can become self-reinforcing regardless of empirical conditions. By creating theoretical justifications for political success under any economic scenario, left-wing movements insulate themselves from the possibility that changing conditions might actually reduce demand for their core policies.

This represents a fundamental problem in political analysis: when theory adapts to justify predetermined conclusions rather than following evidence toward logical outcomes, it ceases to provide meaningful insight into political dynamics.