When State-Building Disrupts Rather Than Stabilizes: French Rebellion in the Run-Up to the Revolution

by Mike Albertus and Victor Gay

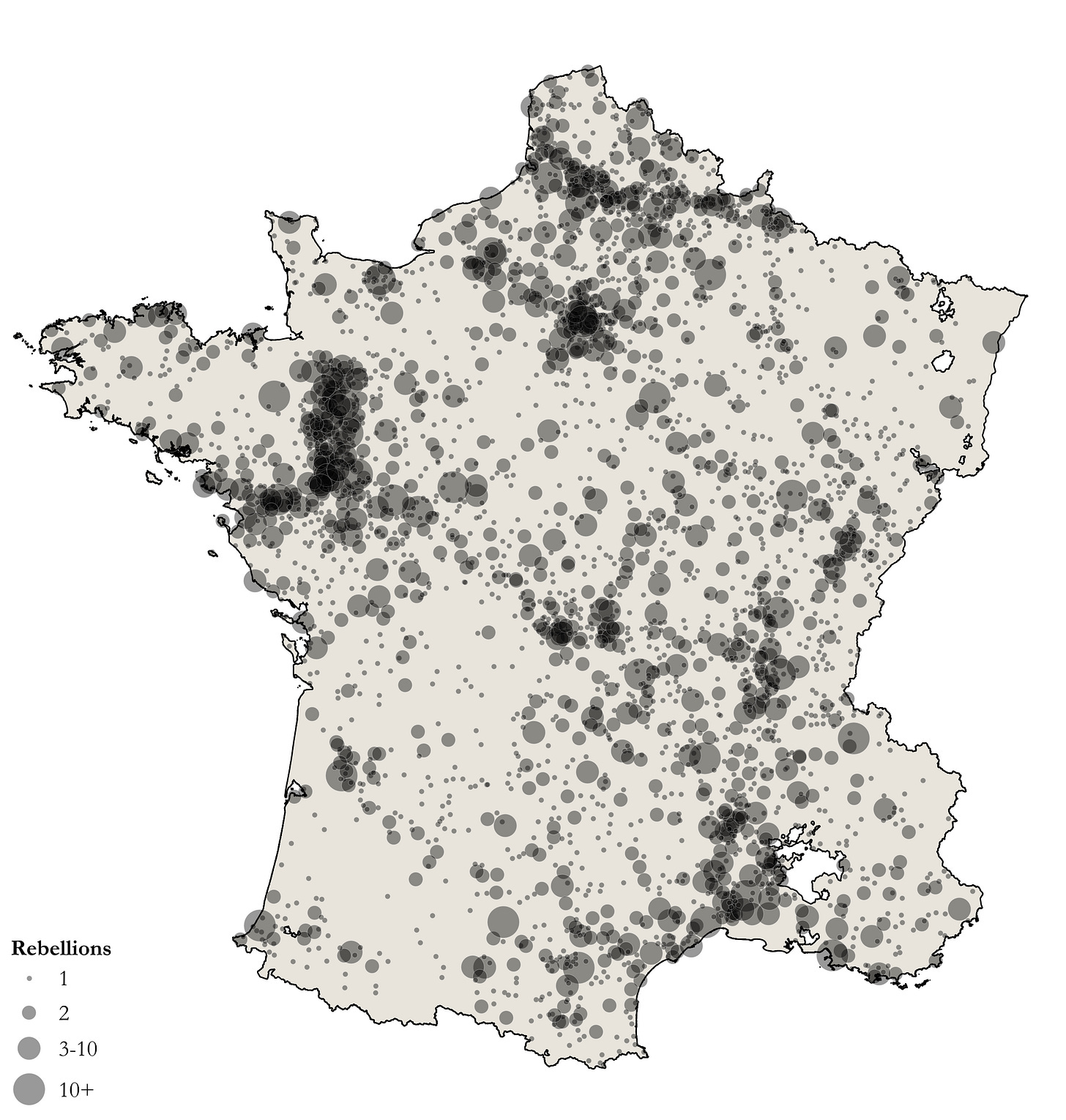

The French countryside simmered with discontent in the century prior to the French Revolution. As the monarchy sought to assert greater authority and control across its territory, building its informational and infrastructural capacity to levels not previously seen, it was met with grievances and rebellion both far and wide (see the map below). Commoners targeted symbols and agents of the royal authority, protesting tax collection, military conscription, and what they perceived as arbitrary or the unfair pursuit of justice. These rebellions would ultimately help set the stage for the French Revolution, one of the most influential and heavily studied political events of the last 250 years.

The Long and Contested Process of State Formation

The emergence and spread of modern nation-states over the past five centuries has been one of the most consequential developments in human history, driving everything from transformative economic development to powerful bureaucracies, the rise of standardized language, and even world wars. Yet building a strong state is a long and complex process. It has taken most states centuries to overcome powerful fragmented regional and religious elites that had private armies and taxation rights, and many states around the world still struggle with fundamental weaknesses.

Along the way, states have sought to penetrate society and centralize control and administration. However, unlike the ultimate result of state-building—which entails social order through the monopolization of violence by the state, the capacity to enforce rules, and central administration of territory and social groups—the process of state-building is far messier and often riven with contestation and contention. Our article “State-Building and Rebellion in the Run-Up to the French Revolution” demonstrates this in the context of pre-revolutionary France, arguably one of the world’s most precocious state-builder, and one which guided and pushed state-building in its neighborhood in continental Europe.

Centralization and Communication as State-Building

A core component of state-building efforts is the expansion of communication routes. By connecting localities more directly to central authorities, this infrastructure strengthens the ability of the state to penetrate society through the control and administration of local activity and rules. Yet the material consequences of increased—though still incomplete—state power can generate social contestation and popular resistance stemming from the greater local capacity of the state to enforce taxes, carry out rules of justice, and conscript civilians. It can also result from the crowding out of private interests and activities in spaces that the state enters. At the same time, the state may lack sufficient coercive power and legitimacy to deter challenges to its authority. The result is a push and pull between the state and society that periodically devolves into violent civil resistance.

The French Horse-Post System as the Monarchy’s Eyes and Ears Across the Kingdom

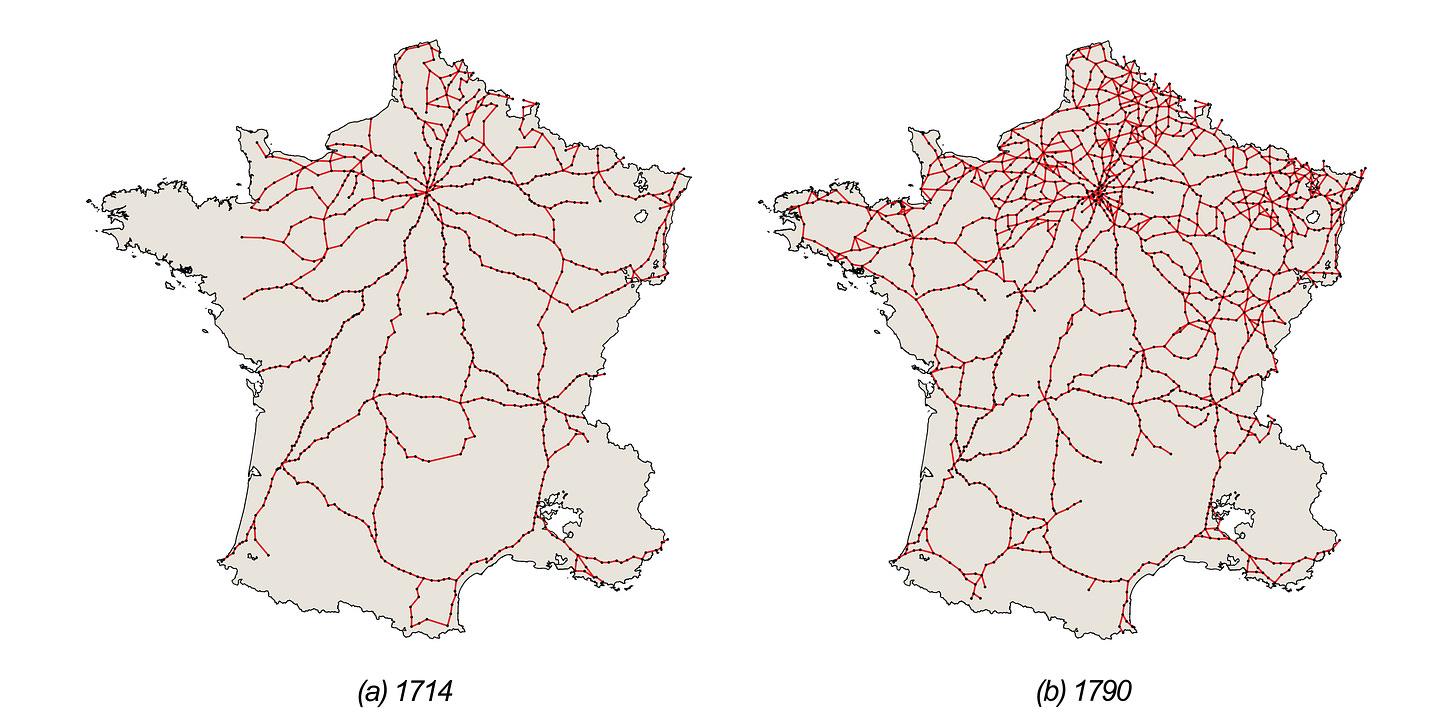

France was caught in precisely this dilemma throughout the eighteenth century. A central element of the monarchy’s state-building efforts was the expansion of the horse-post relay network, which nearly doubled in size over the period (see image).

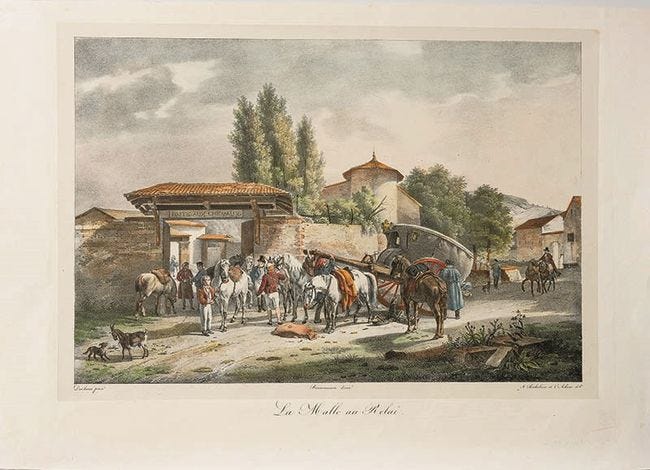

With cars, trains, and telephones still far in the future, these relays established attended lodging quarters and a well-prepared set of fresh horses for messengers carrying information for the royal administration where there had previously been no support. The horse post represented one of the primary means of consolidating the hierarchical French state’s informational capacity as it sought to rule and control a fragmented territory. Located at the entrances to towns or at rural crossroads, horse-post relays were prominent waypoints, comprising stables, lodging quarters, and oftentimes a tavern. Young, sharply dressed horse-post messengers flashed through the countryside between relays (see image). The wealthy local notables that came to staff these waypoints as postmasters effectively doubled as intelligence agents on behalf of the central administration by monitoring passengers and communicating information with regional officials.

Consequences of the Horse Post for Local Order and Rebellion

The development of the horse-post relay network had several consequences. At the national level, it enabled the rapid communication essential to the effective functioning of the state. It allowed central officials, tax farmers, and provincial intendants and local tax officials to coordinate swiftly through directives, reports, and fiscal orders on matters of tax collection and enforcement. That included efforts to suppress salt smuggling across the kingdom’s disparate and consequential salt-tax zones (gabelles). This coordination required frequent and timely exchanges between central administrators and local agents, who were responsible for estimating tax yields and implementing their collection. The horse-post system also facilitated the transmission and enforcement of military recruitment orders, enabling directives to travel efficiently from central authorities to intendants and onward to local recruitment and conscription officers.

Beyond these nationwide implications, the expansion of the horse-post relay network disrupted local social equilibria. Some local actors benefited from these developments. For instance, postmasters gained tax exemptions for their services and other privileges. Local elites also likely benefited from the establishment of horse-post relays, as improved communication with provincial and central authorities could have enhanced their influence and elevated their status.

But others lost out. The various monopolies associated with the horse post crowded out competing private interests. Horse-rental businesses were severely disrupted by the ban on renting their horses along roads connecting horse-post relays. Local farmers and innkeepers situated off postal roads also suffered, as postmasters had priority access to hay and animal fodder for their relays. Additional social groups like commoners, peasants, and merchants may have also lost out as relays brought increased surveillance and stricter enforcement of state regulations. Indeed, enhanced state communication through the horse-post relay network likely made it easier for authorities to monitor and enforce tax collection, military conscription, and judicial decisions.

Backfire During the Process of State-Building

To test this hypothesis, we combine original archival data on the development of the horse-post relay network over the eighteenth century with a comprehensive database of rebellions in pre-Revolutionary France. We digitized one edition of the comprehensive lists of horse-post relay locations (Liste des postes) per decade from the 1710s through the 1790s and mapped them across France. We also digitized comprehensive data from the Jean Nicolas survey of eighteenth-century rebellions, which documents 6,000 rebellions over this period along with their locations, number of participants, and targets. We geolocate these data to roughly 35,000 parishes, the most granular units of administration in Ancien Régime France, and one which no prior study has analyzed during this period.

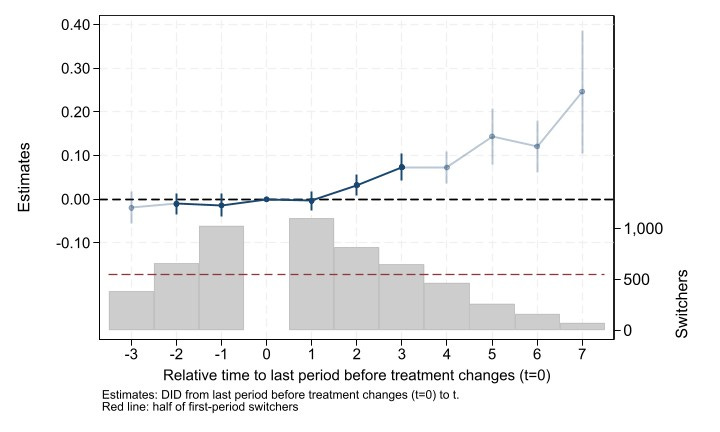

We then use a staggered difference-in-differences design that compares changes in rebellion in parishes that received (or lost) a horse-post relay to those that would later receive (or lose) one. This strategy accounts for fixed parish-level characteristics that might influence both the likelihood of receiving a relay and the propensity for rebellion.

While the initial spatial configuration of the network in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries reflected long-standing strategic political and military concerns, its development over the eighteenth century was primarily driven by the state’s efforts to expand and centralize its authority across the interior of the kingdom, resulting in the densification of the network around major regional nodes. Key to our identification, although the placement of central nodes of the relay network could have been endogenous to regional population dynamics, its local configuration between these nodes was plausibly exogenous, as it was designed to minimize travel time along pre-existing roads, subject to the constraint that relays were spaced 10–15 kilometers apart due to the physiological limits of horses. We exploit local variation in the network through decade-by-administrative division fixed effects, principally relying on within-canton variation—cantons gathered on average 7 parishes and 5,000 inhabitants, with a radius of 6 kilometers.

We find that the introduction of a new horse-post relay in a parish was associated with more local rebellions in subsequent decades (see figure below). We attribute this finding mainly to the material consequences of state efforts at penetrating and ordering local society as it centralized and enhanced its informational capacity. Horse-post relays were strongly associated with rebellions against agents with coercive powers to maintain and enforce order: the military, the police, and the judiciary. They were also associated with rebellions against various forms of taxation as well as rebellions by notables that had private interests along postal roads. Furthermore, while these relationships broadly prevail and encompass the lion’s share of rebellions, we also find a disproportionate response of rebellions to horse-post relays in places of pre-existing state fragmentation and territorial divisions. These findings demonstrate an increasingly powerful state that nonetheless struggled to control local activity across a heterogeneous territory as many of its efforts were contested.

Our empirical approach and additional data give us a unique opportunity to evaluate and challenge several alternative explanations, namely the erosion of traditional social hierarchies, the role of war zones and war involvement, information and collective action possibly spurred by the contemporaneous letter-post system, changes in the recording of rebellions by police brigades charged with keeping order, and the contemporaneous transit infrastructure.

Implications

Our findings have implications for the scholarly understanding of the co-evolution of states, order, and disorder, as well as for the vast scholarship on the origins of the French Revolution. Most importantly, they underscore the importance of conceptually distinguishing the process of state-building from state strength itself. While greater state capacity may ultimately support political stability and order, the process of state-building itself can be disruptive to pre-existing social structures and contested, even for decades at a time. This process likely fueled the accumulation of grievances and repertoires of resistance that ultimately exploded during the Revolution. Indeed, exploratory analyses suggest that, while the horse-post relay network in itself did not facilitate information diffusion among citizens or reduce their collective action costs, parishes that received relays—and experienced an associated uptick in rebellion—were more likely to later host political societies that were critical players during the Revolution.

Michael Albertus is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago. He studies how countries allocate opportunity and well-being among their citizens and the consequences this has for society, why some countries are democratic and others aren't, and why some societies fall into civil conflict. His newest book, Land Power: Who Has It, Who Doesn't, and How That Determines the Fate of Societies (Basic Books, 2025), examines how land became power, how it shapes power, and how who holds that power determines the fundamental social problems that societies grapple with.

Victor Gay is an assistant professor of economics at the Toulouse School of Economics. His work is at the intersection of economic history, political economy, and labor economics.

The horse-post relay as infrastructure for state penetration is a really elegant case study. The ten minute spacing constraint based on horse physiology is a nice natural experiment setup. What stands out is how surveillance infrastructure created its own resitance, the postmasters-as-intelligence-agents thing must have been incredibly visible to locals. I wonder if the conscription rebellions specifically clustered around relay points because thats where draft enforcement was most eficient, or if it was more generalized resentment toward any state intrusion.

Your map of rebellions suggests other explorations to me - high density clusters at key ethnic and religious borderlands (Brittany, Flanders, Provence) and along the “Spanish Road” through former Burgundian possessions. What’s all that about?