Infrastructures of Race? Colonial Indigenous Segregation and Contemporary Land Values

By Enrique de la Rosa Ramos (King’s College London; UK Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs), Guillermo Woo-Mora (Paris School of Economics), and Luis Baldomero-Quintana (William & Mary)

In 1550, Franciscan friar Toribio de Benavente, known as Motolinia, wrote to Charles V about the dispersed and isolated living conditions of Indigenous communities in what is now Mexico City. He suggested a solution: gathering these communities into centralized towns, as in Spain, to aid both evangelization and social order. He lamented that, in their scattered state, many Indigenous people “live more like savages than men” and could not easily be taught the ways of Christianity.1

Motolinia’s observations capture a moment of profound transformation for Mesoamerica. At the time, he was describing the Aztec Empire, a highly sophisticated network of city-states anchored by Tenochtitlán, its capital. This metropolis, now buried beneath modern Mexico City, was one of the largest and most advanced cities of its time. Upon their arrival, the Spanish encountered immense diversity in the region, from small, stateless communities to powerful empires like that of the Nahua, as historian Alan Knight has noted.

The Spanish conquest marked a major turning point, leaving a lasting imprint on the region’s societies and landscapes. Colonial legacies shaped language, religion, and social hierarchies, but their influence extended into the urban fabric in subtle ways. Policies implemented during and after the conquest disrupted the original spatial organization of Indigenous communities, altering the region’s economic geography.2

We study the long-term effects of these colonial transformations on the urban landscape of Mexico City.3 We explore how the conquest and colonial policies reshaped the spatial distribution of Indigenous settlements, laying the groundwork for modern urban inequalities. More than 500 years later, these changes continue to echo in the city’s economic geography, influencing patterns of land valuation. We aim to illuminate how the enduring legacy of colonialism still shapes one of the world’s largest and most dynamic cities.

Colonial Roots of Segregation

In 1538, the Spanish Crown established the repúblicas de indios, semi-autonomous Indigenous communities designed to separate Indigenous populations from Spanish settlers. Officially, these institutions aimed to organize dispersed Indigenous groups, easing governance and social control. While they allowed Indigenous residents some autonomy over tax collection, public goods, and traditions, laws enforced physical segregation, mandating minimum distances between Indigenous and Spanish settlements.

Scholars continue to debate the motivations behind the repúblicas de indios. Some argue they aimed to shield Indigenous people from European diseases, while others see them as tools to maintain social order and reinforce racial hierarchies. Regardless of intent, these repúblicas institutionalized segregation, profoundly shaping the spatial and social organization of colonial Mexico.

The layout of the repúblicas was meticulously planned. Land rights extended 420 to 500 meters from a central plaza, typically home to a church and surrounded by agricultural plots. By the end of the colonial period, two types of pueblos had emerged: isolated ones, distant from Spanish and mestizo populations, and urban-adjacent ones, where land transactions with mestizos, peninsulares (Iberian-born Spaniards), and criollos (American-born Spaniards) were common. Over time, these integrated pueblos facilitated land sales driven by housing demand.

Historian Dorothy Tanck de Estrada’s work has been pivotal in tracing the legacy of the repúblicas. Using late 18th-century censuses and administrative records, she mapped over 4,000 pueblos, including 71 within present-day Mexico City (Figure 1). Her research offers a unique opportunity to analyze the long-term effects of these historical boundaries.

Figure 1: Pueblos’ location in Mexico City

Notes: The locations of the pueblos de indios are based on Tanck de Estrada (2005). Turquoise dots indicate the Indigenous pueblos, and red triangles indicate the mixed pueblos. The thick gray lines represent the boundaries of current-day municipalities of Mexico City. The gray areas represent current-day city blocks. The white symbol represents the colonial central business district (CBD). Historical estimates of urban expansion colored as per Angel et al. (2012).

Measuring the Long-term impacts of Segregation

To explore the enduring impact of colonial segregation on present-day land values in Mexico City, we used the boundaries of pueblos de indios and compared them with contemporary cadastral land plot values sourced from Mexico City’s Treasury. These official appraisals account for factors such as location, land use, and surface area, offering a comprehensive perspective on urban land valuation. By juxtaposing the historical boundaries of Indigenous pueblos with modern land values, we aimed to uncover whether the spatial segregation policies of the colonial era have left lasting legacies in the economic geography of the city.

However, such comparisons are far from straightforward. Land values across Mexico City vary significantly due to a multitude of first-nature and second-nature factors. Soil quality, infrastructure, and neighborhood amenities, for example, play a crucial role in shaping land prices today, potentially obscuring the historical effects we aim to analyze.

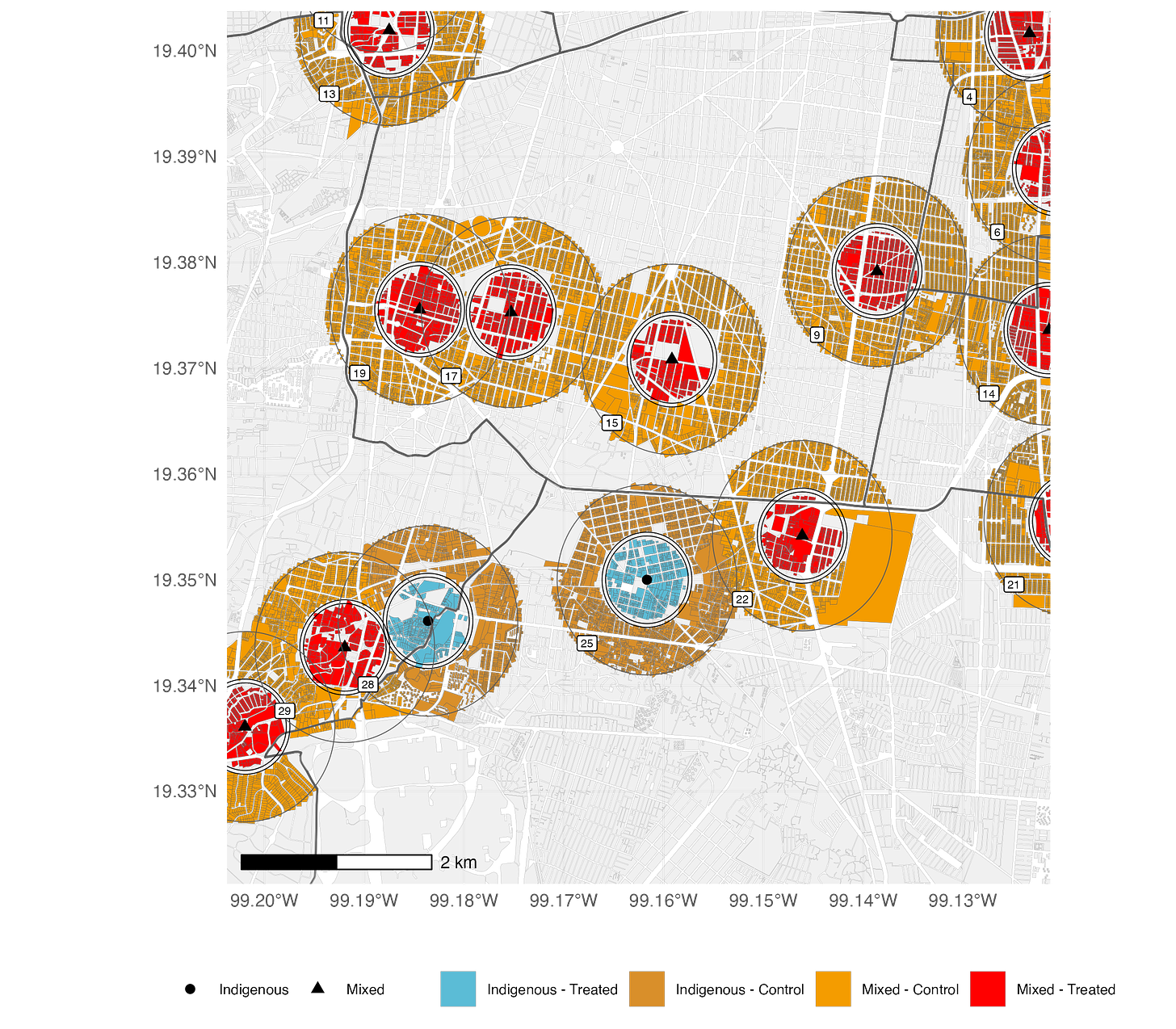

Figure 2: Identification illustration – pueblo locations and fuzzy boundaries

Notes: This map illustrates the two treatment groups and their respective control groups in our spatial RDD framework, zooming in on the Benito Juárez and Coyoacán municipalities. The thick gray lines represent the municipality boundaries. The gray areas represent the land plots. Buffers of three different radii encircle each pueblo: 420 meters, 500 meters, and 1 kilometer. Land plots within blue and red circles lie within 500 meters from the center of the nearest pueblo de indios. Orange plots lie 500 to 1000 meters away from the nearest pueblo de indios center. We exclude plots outside these areas.

To address these challenges, we leveraged historical research to define key characteristics of the pueblos de indios. As previously mention, historical accounts suggest that the radius of each pueblo typically ranged between 420 and 500 meters, with the central plaza serving as the heart of the community. These historical boundaries are central to our analysis, as they enable us to recreate the spatial footprint of the pueblos on the modern map of Mexico City. By doing so, we can credibly compare land values within and around these areas.

Our analysis focused on a defined radius: we compared land plot values within 415 meters of a pueblo’s historical center against those located 505 meters to 1 kilometer away. This approach allowed us to analyze land plots in close proximity to one another, minimizing the influence of confounding variables such as transportation access or local amenities (Figure 2). By controlling for these factors, we aimed to isolate the impact of the pueblos’ colonial legacies on contemporary land values.

Persistent Land Value Penalties

We found a significant "land value penalty" in land plots that overlap with the historical boundaries of pueblos de indios from the Spanish colonial era. Specifically, plots closer to the center of the nearest pueblo have an average value today of 2,100 Mexican pesos per square meter, while plots located 700 to 1,000 meters away from the pueblo center average 2,800 Mexican pesos per square meter. This represents a difference of 600 pesos per square meter, or roughly 25% lower land values within the pueblos. Moreover, using a Spatial Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD), we find a significant land value drop at the boundary: properties just within the pueblo boundary are valued 4.9% to 5.3% lower than those just outside (Figure 3).

The severity of the land value penalty varies depending on the historical composition of the pueblo. The largest penalties occur in pueblos that had predominantly Indigenous populations at the end of the colonial period. In contrast, pueblos with more diverse populations—often located closer to the colonial city center—exhibit little to no land value penalty today. This suggests that proximity to the colonial center may have mitigated some of the long-term effects of segregation, likely due to greater competition for land and a more diverse set of historical influences shaping these areas.

Figure 3: Land value penalties

Notes: Binscatter of the price per square meter of urban land parcels (y-axis) vs. the parcels’ distance to the center of the nearest pueblo measured in meters (x-axis). The gray vertical area is the fuzzy cutoff. The first (second) vertical dotted line marks 420 (500) meters from the nearest pueblo center. The gray vertical line marks 460 meters from the nearest pueblo center. The observations to the left of the gray vertical area are treated units, while those to the right are control unit). The dashed horizontal represents the mean price per square meter for plots within 0 to 200 meters from the center of the nearest pueblo and the mean price for plots with a distance of 700 to 1000 meters from the center of the nearest pueblo.

What drives the persistence?

Despite the many transformations Mexico City has undergone over the centuries—from independence to the global belle époque, the post-revolutionary period, and contemporary urban development—the echoes of colonial segregation imposed by the Spanish Crown continue to shape the city. A central question of our study is this: How can a historical episode from more than 500 years ago still influence land values in modern Mexico City?

We integrate historical evidence with newly digitized historical data to understand how the interaction of economic, political, and institutional factors relate to the long-term impacts of colonial segregation, consistent with the historical political economy framework. Specifically, we identify three key factors that have perpetuated these colonial legacies over time:

Weak Property Rights Protection: After Mexico gained independence in the 19th century, pueblos de indios lost the legal protections that had been granted under Spanish rule. Liberal reforms led to widespread expropriations and land fragmentation, destabilizing property rights in these areas. Indigenous residents faced significant obstacles in generating wealth from their land, as insecure tenure discouraged long-term investment and limited their ability to profit from rising urbanization.

Unequal Provision of Public Goods: During the 19th and 20th centuries, public investments in infrastructure and services were overwhelmingly concentrated in wealthier parts of the city. While central areas benefited from transportation systems, electric lighting, public facilities, and improved sanitation, pueblos and peripheral neighborhoods were largely left behind. This chronic underfunding reinforced perceptions of these areas as low-value, further discouraging investment and deepening the land value penalty over time.

Enduring Social Stigmas: Pueblos have long been associated with poverty and low social status, stigmas that persist to this day. These stereotypes create a cycle of underinvestment, as areas labeled as disadvantaged or overcrowded struggle to attract resources and development. This legacy of social marginalization, rooted in colonial policies, continues to weigh heavily on contemporary land values.

To illustrate these dynamics, we digitized historical maps that trace the distribution of public goods and services across Mexico City over time. These maps vividly demonstrate how infrastructure—such as tramways, public lighting, post offices, government buildings, and paved roads—was systematically concentrated in wealthier areas, leaving pueblos disproportionately underserved.

Figure 4. Historical amenities – Public streetlights by 1932

Notes: Yellow dots represent public lamp post by 1932. The locations of the pueblos de indios are based on Tanck de Estrada (2005). Turquoise dots indicate the Indigenous pueblos, and red triangles (▴) indicate the mixed pueblos. Buffers of two different radii encircle each pueblo: 420 meters and 500 meters. The gray lines represent current-day Mexico City municipalities. The white symbol represents the colonial central business district (CBD).

Even today, while many pueblos now enjoy basic amenities like paved streets and lighting, the quality often lags behind other parts of the city. For instance, schools in these neighborhoods typically have higher student-to-teacher ratios, pointing to continued disparities in educational resources. Finally, we also find housing overcrowding in the blocks within the pueblo’s boundaries.

Conclusion

Colonial segregation policies have left a deep and enduring mark on urban landscapes. A shock that lasted three centuries but ended two centuries ago continues to manifest in significant land value penalties within the historical boundaries of former pueblos de indios. These penalties are linked to negative expectations, weak property rights enforcement, and an underprovision of public goods, underscoring how spatial inequalities rooted in the colonial era persist in shaping modern economic geographies. This resilience highlights the necessity of understanding historical events not as isolated occurrences but as transformative forces with long-term consequences for urban development.

Our findings contribute to the debate about the persistence literature.4 While the compression of history and vague mechanisms often hinder persistence studies, we argue that urban contexts offer a valuable laboratory to address these issues. The granular spatial data available in cities and the frameworks of urban and spatial economics allow us to rigorously explore how historical events influence contemporary outcomes. Moreover, we address the challenge of long-spanning historical analysis by integrating insights from urban historians and archival maps, bridging gaps in fine-grained historical data. In this way, we demonstrate how complementary approaches—combining economic analysis with historical rigor—can enrich our understanding of how past shocks shape the present.

From a policy perspective, the findings emphasize the need for targeted, high-quality investments in infrastructure and public goods to mitigate the lingering effects of historical segregation. Merely expanding access to amenities is insufficient; it is the intensity and quality of interventions that can effectively disrupt entrenched spatial inequalities and foster more equitable urban development in areas historically shaped by segregationist policies.

About the Authors

Enrique de la Rosa Ramos: Ph.D. Candidate in Development Economics and Economic History at the School of Global Affairs at King’s College London, as well as an economist at the UK Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. His research focuses on historical labor markets, examining inequalities in gender, skills, and real wages, alongside trends in top incomes in Mexico from 1870 to 1980. Additionally, he explores the impact of key historical events on contemporary economic outcomes. A crucial aspect of his work involves uncovering and analyzing primary historical materials from archival sources.

Guillermo Woo-Mora: Ph.D. candidate in Economics at the Paris School of Economics. His research focuses on the political economy of development, historical economics, and cultural and social economics, with a particular emphasis on understanding durable or persistent inequalities. His work explores the long-term effects of colonial segregation on spatial equilibrium within cities and the accumulation of human capital through neighborhood identities. He also studies racial inequalities and discrimination, with a focus on colorism. Additionally, he examines the economic impacts of populist policies on economic activity and the influence of populist leaders on public health outcomes.

Luis Baldomero-Quintana: Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at William & Mary. He earned a Ph.D. in Economics at the University of Michigan in 2020. His research focuses on international trade, economic geography, and urban economics. He works with spatial data, administrative records, and historical documents. He teaches Statistics and International Trade.

Nemser, Daniel 2017. Infrastructures of race: concentration and biopolitics in colonial Mexico. University of Texas Press.

Sellars, E. A., & Alix-Garcia, J. (2018). Labor scarcity, land tenure, and historical legacy: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 135, 504–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.07.014

Luis Baldomero-Quintana, L. Guillermo Woo-Mora, Enrique De la Rosa-Ramos, Infrastructures of Race? Colonial Indigenous Segregation and Contemporary Land Values. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 104065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2024.104065

Arroyo Abad, L., & Maurer, N. (2021). History never really says goodbye: A critical review of the persistence literature. Journal of Historical Political Economy, 1(1), 31–68. https://doi.org/10.1561/115.00000002

Very interesting paper. What you name as digital history is an old idea coming from the french economic history of Les Annales, with Francois Furet and his quantitative history approach and some followers in Europe. What it seems to be new is this project of a Historical Political Economy. Far from a classical retrospective econometrics!